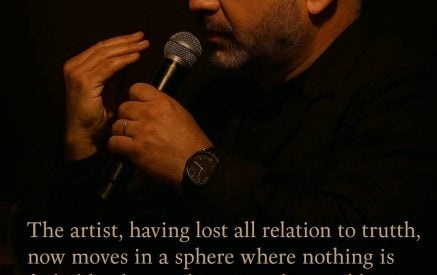

Ruben Hakhverdyan is the most prominent representative of the Armenian copyright song. I am confident that regardless of the further march of this genre in the Armenian art of singing, this estimation of Hakhverdyan will remain unchanged.

There are artists who simply compose or perform pretty well. There are also artists who, besides their art, bring forward a new theory. Ruben Hakhverdyan is one of those. His song has a tremendous impact not only on the sensitive world of the audience but also on their meditations, their way of perception of the world.

Hakhverdyan is a singer of freedom in the very non-revolutionary sense of this word. His song is a complaint not against the social system, the authorities or the leading party but against the bond, the chain that is inside us-inside our brain. The slave may be set free, the social system may change in the country, the jailbird can be released from prison, but what can a man with a stuck mind and a chained brain do, one who is not free in his inner world? Perhaps only the song can save him.

Ruben is singing about love, a lonely wolf, a policeman, a night vagrant, a dog, it doesn’t matter what else he is singing about as his world is one and in this world each of them has its own place. The singer doesn’t exclude anything and anyone, except everything that enchains, hinders. There exist good and evil, black and white in the world. One should get to know evil but never make use of its services. One should love night but never give himself up to dim, never be carried away by dusk. Who not, at times you may wander at midnight as well but instead of “spitting into a puddle you should look for the moon there”.

Not at all underestimating the Russian bards, I want to mention one of Ruben’s great advantages: being a singer of free style he never stoops to the level of Russian “bla-bla” songs, he never mistakes the urban folklore for the latter. Even if in his songs he uses some words one cannot find in dictionaries, in order to emphasize his intolerant attitude towards philistinism, he still remains on his high linguistic level and makes his song bend down before our literary language; he treats his mother tongue, as he says, with white gloves. There is some nobleness in all this.

Ruben overcame the period of absurdity widely known in art and peculiar to many artists mainly due to urban folklore, mocking and excluding the philistinism (“My past”, “Let me, dear”, “Your way”, “Happiness”,) which was followed by another, second period of complaint and revolt (“The ox”, “The dogs”, “Zoo”). Now he is moving forward passing through a more mature period, which is the logical continuation of the precedent two periods. It’s the period of banishment (“Fate”, “Requiem”, “Biography”, “When I die”).

Ruben Hakhverdyan with his art helps us pave the way for becoming a citizen. Ruben helps us become more mature, he helps us remain a child forever, helps us love our town, snow and sun. He helps us love in general. Pondering over his own death he invites people to get drunk and kiss each other at his grave, “When I die, let a girl and a boy kiss each other at my grave”. This is striking scenery and a challenge issued to those who feel fear for death at the expense of life. In this song, pondering over life and death, Ruben curtly passes to the “Soviet rough morals”. By the way, in one of interviews given by him Ruben recalls us-the National Unity Party members rebelling against the “Soviet rough morals”. “Maybe their struggle was a boat in a large river, but they were the only ones to maintain the dignity of our nation. If today I speak about my nation with pride, it’s only due to them”. Our struggle was, unfortunately, not estimated properly before and after it. And Ruben keeps on singing, “But we chose the unsafe life/and sailed the open seas with boys, / in order not to become an obedient captive of the country being devoted to our crazy dream”.

I don’t know who these “boys” are for Ruben, but these lines are very close to my heart.

I also want to speak about Ruben’s boundless love to Yerevan. This love is not pathetic, nor is it pretentious. It is a lucid, persuasive and infectious love. Ruben’s best songs are devoted to Yerevan. I think that Ruben’s songs embody his confession of love to Yerevan; songs which are devoted to the tramps of this town, forsaken mothers, disreputable men, infamous women, those forsaking this town. Ruben, not hesitating a moment, gets identified with them. He sees his own image inside a vagrant of his town (“Requiem”). His “smoked” face is a mirror for the poet-singer. This very tramp is the one to whom he wants to tell the story of his homeless life and the memories of those remote days when “The town belonged to us, /our town belonged to us”. But the town should, first of all, belong to a vagrant… as it is also his home, isn’t it?

And the singer, who is trying to look for the way out of the doorless life, applies to the vagrant, “You have found the way out./ The space is free for everyone” (“Vagrant”).

This is the state when nothing else can be taken away from you.

This is the way Ruben Hakhverdyan looks like-simple but never primitive, free but not violating the freedom limits of the one standing in front of him, full of love, sensible and sometimes imprudent but always boundlessly frank and candid. Complete sincerity and no pretence. Maybe this is the reason that everybody adores his songs-everybody really does-from age 0 to 100. I have seen for many times with what inspiration and enthusiasm the children are singing Ruben’s songs. They even sing songs that are written for 100-year-old people, and even if they don’t understand what the song is about they feel its spontaneity. That’s why they love him. Beyond all question, the adults are as well in need of spontaneity. The adults are also short of spontaneity.

But not Ruben Hakhverdyan…

Razmik MARKOSYAN