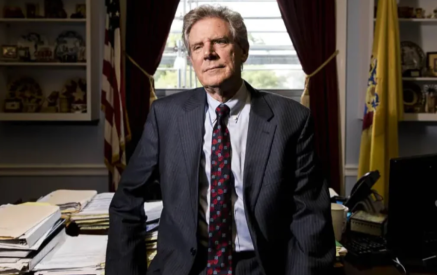

Three World War II veterans, two men and a woman, stand in a salon and raise their glasses in a toast. “What are we drinking?” one man asks. “Victory!” the second replies.

“No, no,” the first man says. “I mean what’s in the glass.”

“Cognac!”

Filmmakers are fond of turning their cameras on parents and grandparents. There is a unique intimacy in this approach to documentary that, depending on the filmmaker’s choices, can infuse a work with the engaging warmth of conversation.

There are shortcomings to this approach too, of course. Family relations are by their nature both parochial and sentimental. Unless used sparingly, obscure dialects of sentimentality can baffle and alienate an audience.

“Embers,” the feature-length documentary debut of Tamara Stepanyan is unsparing. It turns the lens on the filmmaker’s deceased grandmother, also named Tamara (or Toma), whose only visual trace is in a snippet of black-and-white Super-8 film taken in then-Soviet Armenia.

Though Tamara Hakopyan’s absence leaves a pall of melancholy over the film (it begins with a shot of her grave, accompanied by the filmmaker’s off-frame sniffling) “Embers” is not simply a warm bath in personal grief. The 77-minute film is a work of languorous lyricism, one that is puzzlingly successful because at its skeleton is old-fashioned interview-based exposition.

“Embers” had its world premiere last month at the Busan International Film Festival, where it won the Mecenat Award for best documentary film. The work just had its Middle East premiere at the Doha Tribeca Film Festival, where it is screening in the Arab feature film competition.

Stepanyan attempts to document the remaining traces of her subject through interviews with her grandmother’s surviving circle of friends. These utterly unsentimental encounters help transport the film beyond autobiography and through history to a sort of poetry of the ephemeral.

As her voiceover eventually explains, the filmmaker originally meant to reconstitute her grandmother by assembling Toma’s surviving friends, recreating their yearly tradition of gathering on May 9 to mark their participation in the Soviet Union’s victorious war against Nazi invasion.

It proved possible to include only three friends in the reunion. Some members of Toma’s circle were ill or suffered dementia and so were unable to attend. In lieu of this, Stepanyan interviews the survivors. In the process, her search for her absent grandmother becomes a profile of a generation as it remembers, and forgets, itself.

Toma’s friends don’t grieve her loss, but their recollections are nostalgic.

Some of Stepanyan’s informants are more comfortable speaking Russian than Armenian, a mark of their representing the last traces of Soviet Yerevan’s former cultural elite. For them communism didn’t denote an oppressive police state but an ideologically driven social and political project.

In discussing their group’s political activism, Toma’s friends betray a not-unreasoning nostalgia for the past regime and an equal skepticism of the present one.

One gentleman remarks that the Soviet regime was more just than the one that rules Armenia today. His wife adds that it was only later on that they realized how many people had suffered under Soviet rule.

“I don’t think it’s right to criticize [the Soviet] regime,” her husband later insists. “Of course it had its weak points but it had its strengths as well.”

Their nostalgia for the former state, in which they had more of a stake than the present one, is natural. Theirs was a more cosmopolitan era, in which Armenian heritage was secondary to being communist. Given the tribalization of political discourse that tends to follow the collapse of such cosmopolitan systems, it’s hard to not empathize.

Stepanyan’s film is no apologia for Soviet-era communism. Nostalgic testimonials are juxtaposed with silent still-life shots of Soviet-era landscapes – empty parks, silent tower blocks – and empty sitting rooms inhabited by fading 20th-century portraits.

Some informants become less communicative as the interviews wear on. The camera lingers over these silences and, at one point, all Toma’s friends sit in their respective spaces, silent, apparently oblivious to the camera.

Sometimes there is gentle humor in the absence. One lady, who is unable to attend the reunion at film’s end because her memory fails her, is a wellspring of amusing remarks. When the filmmaker seeks to confirm the testimony of other informants that Toma and all her friends were devout communists, the lady denies having been a communist or ever having known one.

Later, when the director asks her about the May 9 meetings, she replies, “I don’t really remember what happened. Ask me something specific so I might remember.”

“The 9 May meetings,” Stepanyan prompts.

“Oh yes, those were happy days.”

“When?”

“Those days in May.”

“What days?”

“When did you say it was?”

“May 9.”

“Yes, 9 May.”

Stepanyan asks the lady if she was friends with Toma.

“Yes,” the lady replies, decisively. “I’m a very friendly person.”

The remark provokes chuckles form the audience but it also provides a light-handed counterpoise to the pervasive weight of nostalgia in works like “Embers.” In a film premised on the centrality of memory and individual identity, it suggests that – for the inhabitants of memories – recollection, and individuality, may be relative.

The Doha Tribeca Film Festival runs through Nov. 24.

Daily Star