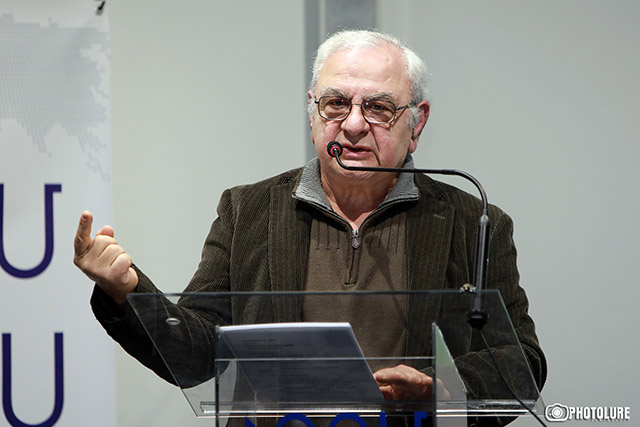

15 years ago, Levon Ter-Petrossian, the first President of Armenia, resigned. There are three main versions of that.

Official: in September 1997, Ter-Petrossian went into detail about the stage-by-stage solution to the Karabakh conflict in an interview and afterwards, wrote the article “Peace or War: The Moment to Get Serious,” the ideas of which were unacceptable for both citizens of Armenia and the majority of politicians and leadership. And in order to save Karabakh, a change of power was needed to prevent that stage-by-stage solution.

The version of Ter-Petrossian’s supporters: Prime Minister Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, the Minister of the Interior and National Security, concentrating huge political and

economic leverage in their hands, decided to get absolute power, deceived Vazgen Sargsyan, the Minister of Defense, and exploiting the Karabakh issue, staged a coup d’état.

Read also

The version of political scientists: after the contentious election of 1996, Ter-Petrossian lacked legitimacy, which he had to make up for by decisive people supporting coercive measures, first of all, Robert Kocharyan, and gradually weakening, he was compelled to hand the power over to them.

These three versions are three parts of the puzzle, which combined make up the whole picture, which the future developments depend on. The official version was justified by the fact that hostilities haven’t escalated into a war in the past 15 years, and thus, the “peace or war” dilemma hasn’t been so topical at least in this period.

Ter-Petrossian’s supporters are right that after 1998, there has been a political and economic system that has ruled out in principle any competition.

In the end, it is also right that relying on law-enforcement bodies, not on citizens’ trust, ultimately brings about negative results. It is just that the first president, being once elected legitimately in 1991, felt more sharply his own illegitimacy in 1996 than those who succeeded him and had never felt the “sweetness” of being elected. Some cultural difference may play a certain role here too.

The resignation of the president itself may be a positive thing, making way for democratic reforms. It happened in Georgia, Tunisia, Egypt, and a set of other countries. However, in all those cases, the president resigned his office as a result of massive protests, realizing that he couldn’t resist the strong popular tide any longer.

However, democratic processes are ruled out, if “certain forces demand resignation.” Such situations cannot arouse enthusiasm and belief in one’s own strength among citizens, because such resignations make people become convinced once again that the situation in the country depends not on them, but on “well-known forces,” which carry a bat and an automatic rifle. People are to complain about those very forces, if their business is not good, they are to curse them, demand pay, pension, justice, and factories from them. Certainly, before 1998, the majority of Armenia’s population had lived according to that psychology too, but after this resignation, it became much clearer that in Armenia, there is no politics in its classical sense – politics as a struggle between ideas that convince or not convince citizens. There are intrigues, treacheries, and the coercion of “jackbooters” (“Yerkrapahs”). Perhaps, the foundation of today’s social apathy was partly laid 15 years ago.

Did the first president do the right thing when on February 3, 1998, he resigned? Certainly, he did the right thing; otherwise “certain forces” would have started a war against forces loyal to Ter-Petrossian. It is just that after May 1994, one shouldn’t have acted in such a way as to cause the situation of February 1998.

ARAM ABRAHAMYAN