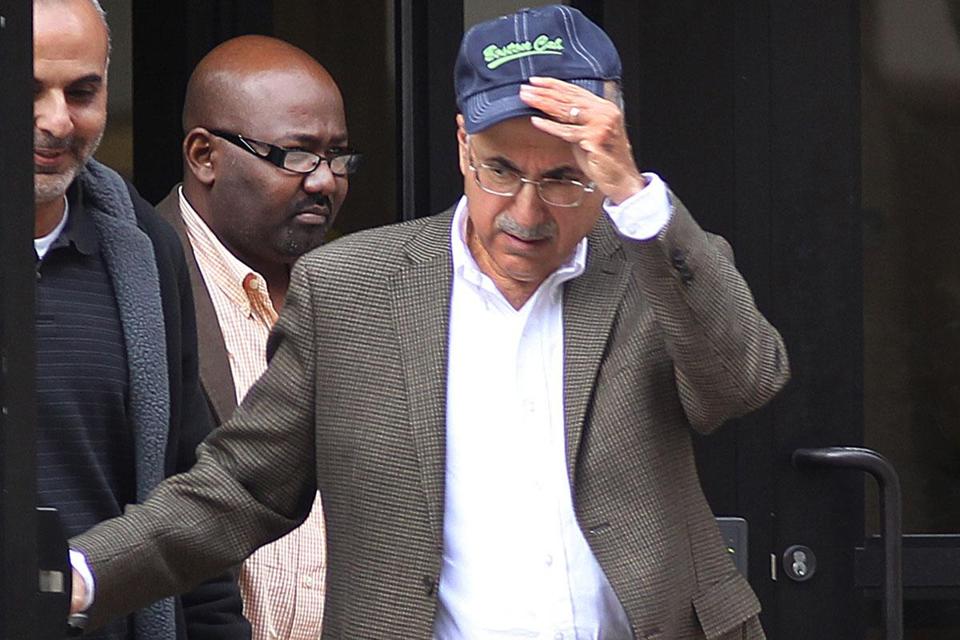

Tutunjian, leaving a Boston court in October, after a trial in a personal injury case brought against his firm.

Faint sunlight slants through dirty windows in the basement of Boston’s biggest taxi garage as a workman with a wrench stands atop a tall ladder, tinkering with a ventilation duct.

Despite his precarious perch, the worker need not worry. A soft-spoken older man wearing a ball cap and metal-rimmed eyeglasses steadies the ladder, leaning into the base with both hands.

Depending on the day, the older man can also be seen collecting $50 fees from baseball fans parking in a lot across the street, a few blocks from Fenway Park. Or watching sports on a television in the dingy Kilmarnock Street garage. A college dropout who doesn’t use a computer, he calls his office there “the cave.’’

He also directs a business empire worth about a quarter-billion dollars.

Edward J. Tutunjian is the king of Boston’s taxi industry, a onetime cabbie who began buying taxi licenses, or medallions, 40 years ago and watched their value soar. Today, he owns Boston Cab and 1 in 5 of the city’s medallions. It is by far the largest taxi fleet in Boston and has won praise from the Menino administration for relying on energy-efficient hybrid Toyotas.

“I felt comfortable in the business, and my drive was to buy more, to expand my business. . . . I was ambitious then.”.

Edward Tutunjian, describing his career as a taxi owner, during a deposition in February in a class-action lawsuit by cabdrivers who say they have been denied fair wages

Squares of tin screwed onto the trunks of cabs, medallions are worth about $600,000 each — or roughly 20 times what Tutunjian paid for his first. They are precious because the city has capped the total at 1,825. With more than 6,000 licensed cabbies in Boston, Tutunjian and other medallion owners enjoy a buyer’s market of potential drivers willing to pay them roughly $100 a day for the opportunity to work.

VICTOR RUIZ CABALLERO FOR THE GLOBE

A worker rested at a vineyard owned by Edward Tutunjian, about 120 miles south of Santiago, Chile. Tutunjian was drawn to Chile by a cabbie who praised his homeland.

A native of Jordan who immigrated to Watertown as a teenager, Tutunjian has become perhaps Boston’s most invisible tycoon, and his 372 medallions bankroll business ventures near and far. He also owns a limousine service and dozens of properties scattered across Massachusetts: Back Bay apartment buildings, lucrative parking lots and garages near Fenway, and multifamily houses west of Boston.

Then there are his vineyards in Chile, which produce Cabernets, Malbecs, and Chardonnays for export. And his business making loans at high interest rates to aspiring taxi owners through the company that bears his initials, EJT Management. And another corporation, Overdrive Media, which sells space for advertisements displayed on taxi roofs.

But Tutunjian’s signature enterprise is Boston Cab, and he runs it with a hard edge that seems at odds with his genial mustachioed demeanor. Boston Cab drivers interviewed by the Globe described having to pay small bribes to get shifts. To buy Tutunjian’s gasoline even when their tanks are full. To scrape up an extra $10 or $50 whenever the garage claims, without proof, that they underpaid the day or week before.

Drivers say they endure these indignities in the garage owned by “Mr. Eddie’’ because of the Boston taxi industry’s unforgiving mathematics: There are more than three drivers for every taxi authorized by the city.

“He does what he does because there are so many drivers looking for a cab,’’ said Jephtet Roseme, a Haitian-born driver for Boston Cab. “If you say you’re not going to take it, he’ll find 20 people, 30 people to [take your place].’’

There is no evidence that Tutunjian, 63, takes bribes for keys himself. He told a reporter who visited his garage that he wouldn’t tolerate employees taking bribes and that he tries to be fair to drivers.

“I started as a driver,’’ he said. “And I know where they’re coming from.’’

In a written statement, he called the drivers’ allegations of exploitation “false and troubling.’’ No driver had ever complained to him of being asked to pay a bribe, he wrote. Nonetheless, he recently met with each of his employees and told them they would be fired if they took one. Cabbies are only charged for gas if they fail to top off the tank, he added.

Tutunjian, who lives in a handsome $1.3 million Colonial at the end of a cul-de-sac in Belmont, declined to be interviewed at length. His nephew and second-in-command, Armen Mahserejian, said his uncle “doesn’t like to attract a lot of attention. He likes to run the business and service the neighborhoods and the industry.’’

But a picture of the taxi mogul slips into focus through interviews with people in the taxi industry and the local Armenian community and from testimony Tutunjian and his associates have given in personal-injury and employment lawsuits.

Admirers call Tutunjian’s rise from a slender teenage immigrant with black-framed eyeglasses to the multimillionaire owner of a ubiquitous taxi fleet an inspiring tale.

“Anybody can do it,’’ said Vartkes Moushigian of Watertown, who described himself as a relative through marriage. “If you’re steady and you work hard, opportunities come and they fall into your lap.’’

By many accounts, Tutunjian has indeed worked tirelessly since entering the business in the 1960s. He repaired his own cabs, replacing brakes, changing oil. A rival fleet owner recalls Tutunjian driving a tow truck at night to service his taxis. Despite his millions, Tutunjian still shows up to the garage at least six days a week.

“He’s just passionate about it,” said John Moore, a Cambridge architect and environmental activist who persuaded Tutunjian to start buying hybrid taxis in 2006. “I think his work, that’s his life.”

From Jordan to Watertown

Tutunjian was born in Amman, Jordan, in 1949, one of five children of Armenian descent. Their father died when Edward — whose Armenian name was Adour — was a young child, and his older brother George supported their family as a mechanic, according to a 2005 obituary in a taxi industry publication for George Tutunjian, who later owned a number of Boston medallions.

The family immigrated to the United States and, like many other Armenian families in Massachusetts, settled in Watertown. Edward spent a year at Watertown High School, where he played on a winless soccer team, according to the 1967 yearbook. He studied business for a year at Bentley College, then dropped out after a cousin introduced him to cab driving.

Tutunjian bought his first medallion in 1972 or 1973 for about $30,000 but kept driving for another six or seven years. His evolution from taxi driver to fleet owner could not have been timed better. In 1974, the Boston police, under pressure from medallion owners, began letting them lease cabs to “independent contractors”, a practice that would become common in many US cities. That meant owners no longer had to pay cabbies wages and benefits, as had been the custom for decades.

JOHN TLUMACKI/GLOBE STAFF

In addition to his home in Belmont (above left), Tutunjian’s real estate includes an apartment building on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston (above right), a building that houses a Kilmarnock Street restaurant, and other commercial properties on Kilmarnock.

Tutunjian accumulated medallions slowly at first, then in bursts, refinancing loans on his increasingly valuable medallions to buy more. Over the years Tutunjian has borrowed tens of millions of dollars, using the medallions as collateral.

“I felt comfortable in the business, and my drive was to buy more, to expand my business,” he testified in February in a deposition in a class-action lawsuit by taxi drivers who say they have been denied fair wages and benefits. “I was ambitious then.”

By the time he had more than 50 cabs, he once testified, he started losing track of the drivers’ names and faces. In 2000 he doubled his fleet, buying about 160 medallions from the daughter of the late Checker Taxi founder Frank Sawyer, a legendary power broker and real estate baron.

Today, the Tutunjian fleet is about seven times as large as his nearest rival’s, Tudor Garage.

In recent years, Tutunjian has diversified, sometimes in improbable directions. Drawn to Chile by a cabdriver who praised his native country, Tutunjian bought vineyards there and now exports wine under labels including Apaltagua and Tutunjian Single Vineyard.

His wineries were among several hundred exhibitors at the Boston Wine Expo in February at the Seaport World Trade Center. A young woman who sampled one of his Cabernets said it was better than others she had tried that day and would go well “with something hearty, like a burger.’’

Despite his foray into international commerce, Tutunjian’s approach to business remains decidedly homespun. He testified in 2008 that he didn’t use a computer. The following year, he negotiated one of his bigger taxi purchases at Victoria’s Diner on Massachusetts Avenue, agreeing within minutes to pay retiring fleet owner Edward Kempner $9.4 million for 26 medallions.

Tutunjian explains his business decisions as pure instinct. “Sometimes my head says sell this property,’’ he once testified.

While Boston Cab is the name Bostonians recognize, emblazoned in distinctive brown cursive on the side of cabs, that is technically just Tutunjian’s dispatch service, which connects customers with his 372 taxis and about 100 taxis owned by others who pay Boston Cab a weekly fee. Most of Tutunjian’s taxi business is run by the eponymous EJT Management.

It is a family operation. Mahserejian and another nephew, Raffi Chapian, primarily handle the cabs and their drivers. Tutunjian’s older daughter, Mary Tarpy, directs his wine imports. His son, Peter, graduated from Clark University a few years ago and now works in the garage. Asked Peter’s title in the February deposition, Tutunjian answered: “Owner’s son.”

Since 2006, Tutunjian and his family have contributed more than $13,000 to political candidates in Massachusetts, most of it to Mayor Thomas M. Menino and members of the City Council.

Tutunjian is a familiar figure in Watertown, where he recently provided wines to an Armenian street festival and donated to a local church. And his roots are visible at the garage, where small hand-scrawled arrows point like road signs to two touchstones in his life — “Amman” and “Boston.”

He claims to preside over his flock of hundreds of drivers with almost fatherly warmth. At the annual Christmas party at the garage in December, cabdrivers munched on stuffed Armenian grape leaves made by Tutunjian’s wife.

“I don’t hide behind a desk,” he said in a 2007 deposition. Drivers “can ask me any question they want from baseball to traffic to politics. I’m open for all.”

Indeed, many drivers say Tutunjian is an amiable presence in the garage. But, they add, he has at times stood by as his nephews dressed down drivers in disputes over fees, ridiculed their ethnic backgrounds or physical disabilities, and treated them with contempt.

Ahmed Ali Farah, a Somali immigrant who walks with a limp as a result of childhood polio, told the Globe that when the wheels of the cab he leased accidentally scraped the frame of the car wash in Tutunjian’s garage, Chapian confronted him and said, “If I knew you were handicapped, I would not have given you a vehicle.’’ Farah filed a civil rights lawsuit against Tutunjian in 2004 but didn’t have the money to pursue it.

“Mr. Eddie puts two lions in front and then he’s like, how would you say, a teddy bear,” said another former Boston Cab driver, Robert Bruce.

‘The humiliation window’

Drivers who want to lease a taxi at Boston Cab for 12 hours usually begin arriving at the garage around 3 a.m. for a day shift, and around 3 p.m. for a night shift. In the afternoons and evenings, Tutunjian and one or both of his nephews are often behind the window where many cabbies, particularly less seasoned ones, slip the dispatcher anywhere from $2 to $20 in order to avoid waiting for hours or even going home empty-handed.

Some drivers call it “the humiliation window.”

An occasional Boston Cab driver from Morocco described his initiation three years ago. He sat in the waiting room for hours every day. For two weeks. But no one called his name. Finally, another cabbie let him in on the unwritten rules: He should slip the dispatcher $5 or $10, the driver recalled. And he did, for every shift.

Tutunjian, he said, had to be aware of the shakedown.

“He’s there all the time,” said the 40-year-old man, who insisted on anonymity because he fears retaliation. “Sometimes he’s standing behind [dispatchers] when they give out the keys and you slip them five bucks.’’

Some drivers told the Globe that they refused to “tip” and still managed to get shifts — and that was true as well for a Globe reporter who drove eight shifts at Boston Cab. But if only a fraction of drivers tip each day, that adds up to thousands of dollars each week flowing into the pockets of the garage’s overseers.

Kempner, the retired fleet owner who sold medallions to Tutunjian, said the payoffs at Tutunjian’s garage are an open industry secret, although he blames employees working behind the window, not Tutunjian.

“Let’s just say there’s Eddie, and then there’s his window,’’ Kempner said. “I’ve heard enough to know that there’s something going on.”

In the case that challenges Tutunjian’s practice of leasing cabs to independent contractors instead of hiring employees, Tutunjian testified that he strictly adheres to the more than 50 pages of regulations issued by the police hackney unit, which regulates the taxi industry. “We obey the rules,’’ he said.

Yet his firms engage in some business practices that appear to be flagrant violations of hackney regulations. They include failing to give drivers receipts and pressuring them to buy his gas at about 35 cents per gallon above retail.

In 2007, hackney determined that Tutunjian was overcharging all 82 drivers who leased his medallions to use on their own vehicles. In addition to improperly passing on to the drivers city fees that were his own responsibility, Tutunjian was requiring them to pay $80 weekly dues to subscribe to the Boston Cab dispatch service. Under city rules, drivers who lease medallions have the right to pick which dispatch service to join — and Boston Cab is the most expensive.

The city required him to renegotiate the leases but imposed no sanction.

Empire expands to limos

If the people who drive Tutunjian’s brown-and-white cabs are described by some as urban sharecroppers, the chauffeurs in the limousine company he started more than a decade ago were all but indentured servants.

Boston Car Service charged some 70 chauffeurs, many of them poor immigrants from Africa and the Middle East, as much as $105,000 in membership fees in order to work. They were deemed independent contractors but allegedly signed agreements banning them from driving for any other limousine service.

The chauffeurs bought their own black cars for up to $50,000, paid $50 a week for two-way radios that were never installed, and turned over to management 21 percent of their fares. Some chauffeurs borrowed the membership fees at 15 percent interest from Boston Car Service or a company set up by one of Tutunjian’s top managers.

Boston Car Service promised chauffeurs that they would earn $120,000 a year, two former drivers told the Globe. Instead, several said they ended up broke. One showed the Globe an August 2011 paycheck bearing Tutunjian’s signature for $1.75, which the driver said represented his entire income for that week.

In August, Tutunjian reached a $7 million out-of-court settlement with the drivers and agreed to start paying regular wages and benefits.

“Most of the people who worked with Boston Car Service, they don’t know the law. They’re a bunch of illiterate people,’’ said one of the plaintiffs, an Algerian-born chauffeur who has left the company but requested anonymity because he fears retribution. “I believed in the scam.’’

Four months before both sides settled the class-action suit, Tutunjian was honored by the city of Boston for converting most of his taxi fleet to hybrid Toyotas.

In a ceremony at Gillette’s headquarters in South Boston, Tutunjian held up a green plaque for the cameras as an aide to Menino extolled Tutunjian’s “pioneering leadership.’’ Boston Cab’s website even features a picture of Menino posing next to a Boston Cab with the city’s signature for hybrid cabs, a bright green stripe.

But if Tutunjian is a friend of the environment, it marks an extraordinary reinvention.

EJT was among five Boston area taxi companies that together were fined more than $93,000 in 1992 by the federal government for tampering with emission controls of cabs. Eight years later, the city sued him for improper disposal of hazardous waste at a garage Tutunjian owns on Dudley Street.

And in 2008, the Registry of Motor Vehicles moved to revoke EJT’s ability to inspect cars after it repeatedly claimed that vehicles, including at least one of Tutunjian’s cabs, passed fuel emission tests they had not. Tutunjian’s lawyers challenged the ruling, and his inspection service was only suspended for 30 days.

Tutunjian told the Globe in a statement that his companies have “a very strong environmental record.’’ He said the federal fine was small and that he fired the mechanic responsible for the fraudulent state inspections.

If Tutunjian hewed to the city’s rules, his business would remain very profitable, as it is for other Boston taxi owners who bought medallions at comparatively bargain rates. In 2000, his cab operation boasted an enviable 42 percent “net operating profit” margin, according to a 2001 internal memorandum by Sovereign Bank that analyzed the business before lending $19 million. The bank document was later revealed in a personal injury lawsuit.

Much of that profit flows into the garage as a river of cash. After each shift, drivers stuff their leasing fees in zippered plastic pouches and put them in a drop-box chute. The cash goes into a safe in the back room.

In 2009, two masked men forced their way into that back room after pistol-whipping a dispatcher. They made Mahserejian and Tarpy lie on the floor at gunpoint and stole more than $21,000. They missed considerably more cash in the room, according to Boston police reports and court files.

In 2004, Tutunjian reported to the Internal Revenue Service income of about $30,000 per medallion. But leasing prices and estimates from the hackney department’s finance consultant about how often taxis are in service suggest that each medallion should have earned several thousand dollars more that year.

Tutunjian declined to discuss his tax returns, except to note that they are prepared by an independent accounting firm in compliance with the law.

It is impossible to know exactly how wealthy Tutunjian is, since his companies are privately held and highly leveraged. But according to the Sovereign Bank memo, he and his wife’s personal net worth, separate from his businesses, was $10.7 million in 2000. Their income was almost $5.5 million in 2003, his accountant later testified.

The loan document, for which Sovereign Bank employees interviewed Tutunjian, also contains curious errors. In describing the strength of his management team, it reported that Mahserejian had a business degree. In fact, he has repeatedly testified that he dropped out of community college after a football injury. The document also says another nephew of Tutunjian’s, Gabriel Tutunjian, had a business degree from Northeastern University. He does not.

Tutunjian told the Globe that he didn’t know who completed the bank memo.

The intervening years also appear to have been good to Tutunjian. As the board of directors of the limousine company, he and Tarpy, his daughter, approved $7.7 million in stockholder dividends between 2004 and 2010, according to documents that surfaced in the chauffeurs’ lawsuit. Tutunjian testified last year that he was the sole owner of the company.

As for Tutunjian’s future, he said in his February deposition that he is not looking to increase his share of the 1,825 taxi medallions in Boston, but he is still in the market.

“Yes,’’ he said, when asked if he is continuing to buy cabs. “It depends on what mood I am in.”

Bob Hohler and Thomas Farragher of the Globe Spotlight Team contributed to this report.

The Boston Globe