Foreign policy. Stepanakert, Mountainous Karabagh — I no longer know what to do on April 24—or where to go. This is the day Armenians across the globe commemorate the genocide in 1915 that destroyed the Armenian people and its homeland of thousands of years.

Those killing fields, the homes of my grandparents, are located in historic western Armenia—now eastern Turkey. But a century later, this very region has erupted in all-out war. Turkish forces are on the offensive again, this time, Armenians having been eliminated, against an empowered Kurdish majority. For an Armenian, it is a difficult place to travel to on April 24—to assert our memory amid the bombshells and havoc of another people’s national struggle.

In Washington earlier this April, I was taking several meetings with the Department of State and at other offices. As it is known, official Turkey still denies that genocide was ever committed. And it expects its “strategic partners,” such as the United States, not to call it by that name.

In the past week, respected national newspapers shamefully published Turkish ads denying the Armenian Genocide. Denialist billboards went up, too. And in his address this April, President Obama called the events of 1915 everything but “genocide.” You can see why Washington, too, is also a difficult place to be on April 24.

Read also

So I decided to return to Yerevan, Armenia, for April 24. To be clear this is modern-day Armenia—just a sliver of the great homeland which survived 1915, was absorbed into the Soviet Union, and eventually declared independence in 1991. This is the Armenia, whose foreign minister I was and whose flag I raised at the United Nations. Here millions of Armenians and their guests—this year George Clooney, Charles Aznavour, and others—march up to the Eternal Flame of 1915 and lay flowers every April 24.

But even Yerevan, this year, was a difficult place to be on April 24. Because the minds of Armenians were elsewhere. They were drifting a couple hundred miles southeast—where, even as we commemorated the victims of the Armenian Genocide, the groundworks of a new genocide against us were being laid.

A lot has been written about Nagorno (Mountainous) Karabagh, or Artsakh; people have different opinions of it. But the simplest and most irrefutable narrative is this: For as long as we know, since the ancient Armenian kingdoms, Mountainous Karabagh has been an Armenian cultural cradle. Even when Josef Stalin and his Bolshevik entourage, in order to placate nationalist Turkey, unilaterally transferred these lands from Soviet Armenia and subjected them as an autonomous region to Soviet Azerbaijani rule in 1923, Mountainous Karabagh—unlike Nakhichevan to its west—managed to keep its majority Armenian population.

As the USSR collapsed and the people of Artsakh voted by lawful referendum to declare their own independence from Azerbaijan, Baku in turn unleashed all-out war—and lost. As sovereign Armenia’s foreign minister, I helped launch the peace process in Helsinki in March 1992.

Twenty years later, this April, Turkey-allied Azerbaijan launched its largest campaign of racist aggression since the Russian-brokered ceasefire that had been signed in 1994 among Azerbaijan, Mountainous Karabagh, and Armenia. For four days, Azerbaijan’s drones and helicopters bombed peaceful Christian Armenian civilians. Soldier and villager alike were taken captive and, ISIS-style, beheaded alive in such inhumanity that even transcends the definition of a war crime.

From Stepanakert, the capital of Mountainous Karabagh, I can now report the following. Azerbaijan’s belligerent conduct, a hell-bent design developed over the years to wipe out not only Karabagh but Armenia in toto, renders a negotiated settlement no longer possible, and it is imperatively time for the international community to take a stance in equivalent application of international law and, yes, in pursuit of guaranteeing strategic security interests.

The United States, Europe, and their partners to the east and south must officially recognize the Mountainous Karabagh Republic within its constitutional frontiers. It is no less deserving of recognition, under the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, than Kosovo, East Timor, Eritrea, or South Sudan.

It gives no consolation that Azerbaijan is a blatant clan-based dictatorship or that official Ankara is in the throes of realizing xenophobic rhetoric domestically and in foreign affairs, but it would help along the way if the Republic of Armenia itself, naturally among the first to recognize, put its own democratic house in order, rooting out the corruption of its own authorities, systemic fraud and falsification, stolen elections and political prisoners.

This is a complicated issue indeed; let us not pretend otherwise. But on the verge of a new genocide this April, let us also not mince words and find pretext for inaction.

Armenians living peacefully in Mountainous Karabagh were murdered this April. They will be murdered again. Do you recognize a genocide when you see it?

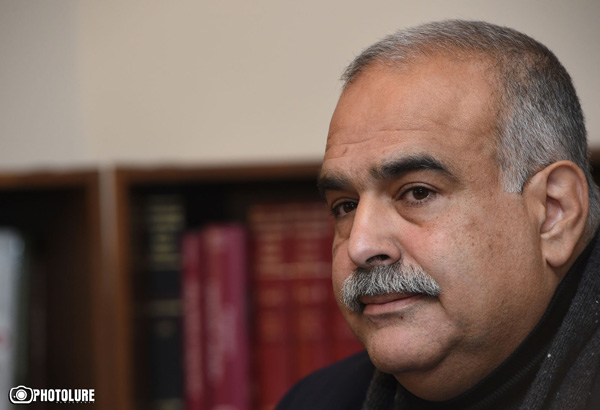

Raffi K. Hovannisian