By Fernando Peregrín Gutierrez

The singing school of the Komitas Conservatory in Yerevan is directed by renowned professor Tatevik Sazandaryan who counts as assistant another wonderful and renowned teacher, Svetlana Kolosaryan. Among the young and sought-after singers from this school are Lianna Haroutounian — who is an accomplished Verdian (Don Carlo and Il trovatore) and one of the best “Madama Butterfly” of the current lyric scene —, the sopranos Hasmik Papian , Karine Babajanyan; the lyric soprano of coloratura Hasmik Torosyan—who is doing a great artistic career in Italy—, and the rossinian mezzo Varduhi Abrahamyan, recently very applauded in the Liceu of Barcelona.

These days (24th October), the aforementioned soprano Lianna Haroutounian has returned to sing at the Teatro Real de Madrid, this time as “Leonora” of Verdi’s Il trovatore . a role in which she recently achieved great success at Covent Garden ROH, London. Two seasons ago he sang with remarkable success in Madrid “Desdemona” from Verdi’s Othello, a role that does not suit his voice and conditions as an actress as “Leonora”.

Read also

He obtained in Il trovatore a remarkable triumph and was, together with the Russian mezzo Ekaterina Semenchuk, “Azucena”, with difference, the most outstanding. This Armenian lyric soprano is a singer of great musicality and impeccable tuning. It has a great technique, ease and beauty in the acute record and in the agility, very orthodox breathing and emission techniques, and timbre with good metal, voice perhaps more tan and dark than those usually associated with the so called Italian vocalità. He made good filati in his great aria of the first act “Tacea la noctte placida”, although not spectacular (in that, the Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballé exaggerated somewhat). Better still was his aria “D’amor sull, there rosee” of the last act, in which he gave a whole lesson of Verdian singing.

Ekaterina Semenchuk, Russian dramatic mezzo, was superb in her role as a gypsy. One of his best successes was when she sang in pianissimo, lying down and as in a dream, her aria “Ai nostri monti…” In this performance at the Teatro Real, it was interesting to compare the ways of singing of Lianna Haroutounian, the Armenian arisen from Komitas, and Ekaterina Semenchuk, raised from the St. Petersburg Conservatory, like the much yearn for Yelena Obraztsova, and trained at the Mariinsky Theater. Both great Russian mezzo-sopranos were when young singers closely linked to the great opera house of St. Petersburg and to the Bolshoi.

“Manrico” was sang by the reconised Italian tenor Francesco Meli, who defended his difficult role with determination and good will. But when it was time for the tenor to shine on “Di quella pira…” (who he sang half tone down), he was unsafe and unconvincing, with a lack of squilo and fiato in C 5 (but half tone down) “All’armi” (interpolated –added—by tradition) In general, this whole scene was badly conceived, insipid and lack of needed spectacularism by the regisseur Francisco Negrín.

The French baritone Ludovic Tézier accomplished without much boast, with a voice to lyrical for “Il conte di Luna” and monotonous and somewhat bland phrasing, which was especially noted in his beautiful ria “Il balen del suo sorriso”.

Well, with a beautiful voice and good knowledge of Verdian style Roberto Tagliavini as “Ferrando”, although his performance was dimmed by the whims of the stage director.

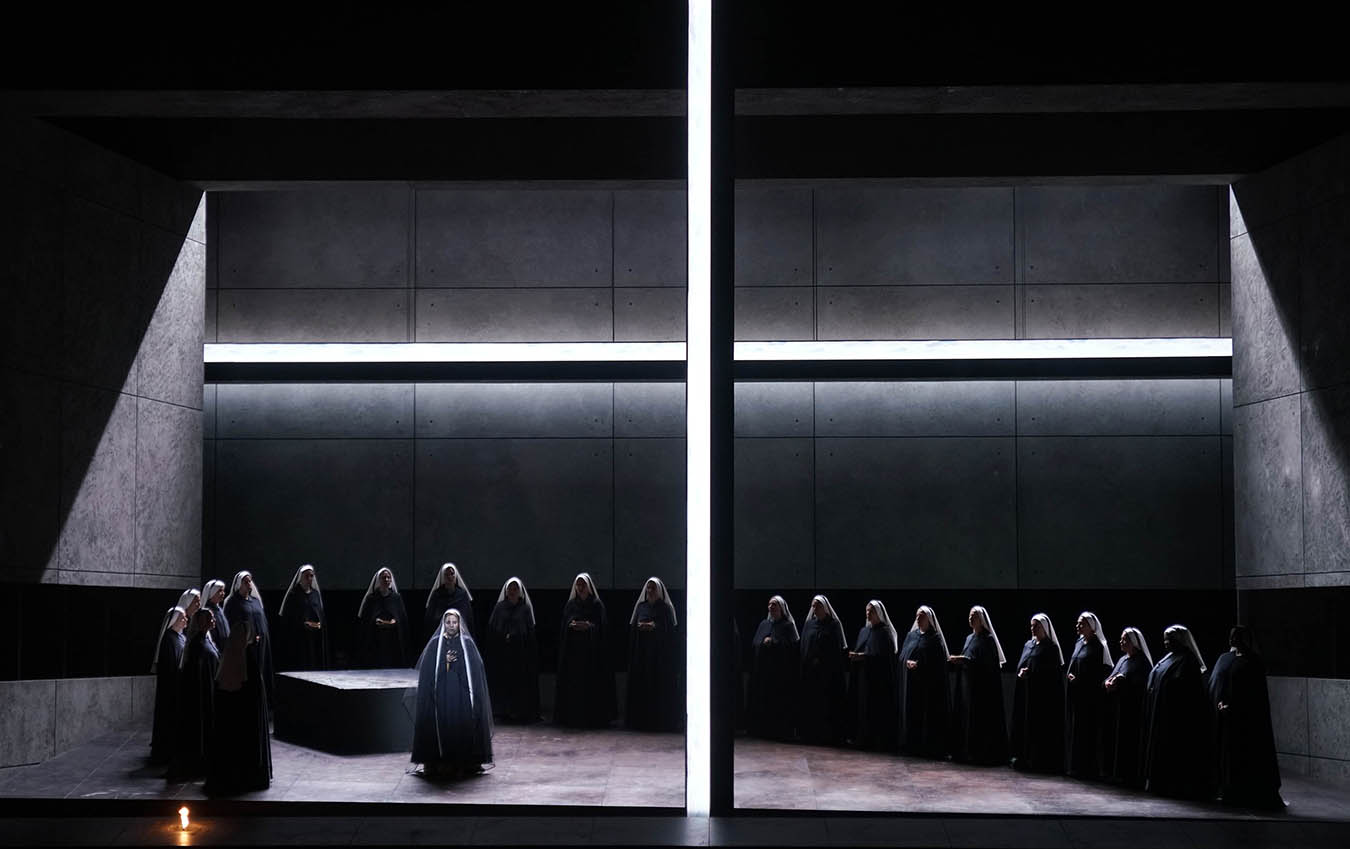

What was carried out in Madrid by Francisco Negrín and his set and customs designer Louis Desieé has been vulgar, soulless and ugly. To sum it up, one could say that a Trovatore without gypsies, uomini d’arme (armed men), turrets and gardens represented with the irrationality proper to romanticism, and not with the geometric minimalism of modern rationalism; set in what closely resembles the entrance hall of a modern high-walled office building or a reception hall of a Ministry, full of windows where to deliver “the papers”; with gas burners more typical of grills and barbecues than of fires in gypsy camps; with five or six children who did as an audience to the initial narration of “Ferrando” and afterwards played games of battles with swords in the absence of real rival military parties — replaced, by the way, by groups of zombies that served also as spectators of the plot—; with nuns gossiping and “Manrico” wearing black suspenders in the last acts, it is a joke in bad taste.

The musical aspects of the performance were in charge of the Italian conductor Maurizio Benini, a good concertatore (harmoniser) rather than inspired Verdian. He took care of the details and achieved a good balance between the pit and the scene. The orchestra of the Teatro Real gives its best in the Verdian repertoire. Too bad the strings did not sound with the necessary intensity and in some passages they were covered by the brass instruments. Successful wind and wood soloists. The choir, not very numerous, was harmed by the mistakes of the stage director by not allowing its members to sing grouped, dispersing them throughout the scene.