The Human Rights Ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) Artak Beglaryan, on September 30, with the initiative and support of the Armenian Delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, participated in the event on human rights protection in de facto states organized at the PACE, Strasbourg.

A.Beglaryan and former chairperson of the French Delegation to the PACE René Rouquet had talks on the topic. Number of delegates of the PACE, diplomats, as well as experts and Council of Europe officials were present at the event.

The full text of the Ombudsman is given below:

“Dear colleagues, dear friends,

Read also

I thank to the Armenian Delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe and personally Mr. Ruben Rubinian, the head of delegation, for providing this opportunity to speak about human rights in de facto states and the role of the Council of Europe. It is an honor to share this panel also with Mr Rouguet, who understands really well the topic of our today’s discussion. I think this is the first time that the authentic voice of Artsakh will be heard within the Parliamentary Assembly. So, this event is making history…

Let me start by quoting the Article 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

“Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in the Declaration, without distinction of any kind. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.”

So, human rights are declared universal, but what about the reality?

I would prefer to respond with the mouth of former Secretary General of the Council of Europe Thorbjørn Jagland, who in 2014, as a particular challenge to the almost 3 million people living in conflict zones in Europe, highlighted in his report that “Protecting the human rights of people living in unresolved conflict zones is often not the first priority of the international community when coping with the difficulties of trying to settle these conflicts”. It was an important confession, because any conflict settlement should be aimed, first and foremost, at human rights protection.

However, as usual, here too the reality is in stark contrast with wishes and declarations. The reality is that in the area of the Council of Europe, millions of people don’t have proper access to international human rights protection bodies and programs, as well as international aid and development. They are the people of living in de-facto states, which have been formed as results of conflicts, but have not been formally recognized by the international community.

To understand the extent of the issue, it is worthwhile to mention that 17% of cases pending before the European Court of Human Rights relate to these unresolved conflict areas. I think the percentage will grow further, unless the situation changes positively.

Modifying George Orwell’s truth, it turns out that all the people are equal, but some of them are less equal…

Why are not “less equal” people equal to “more equal” people?

The short answer has 2 parts:

A) Because of the lack of political will of international community to enforce its standards. It often dwells into politics and bargaining instead of focusing on human rights protection;

B) Because of the stiff opposition of some member states of the Council of Europe, which are involved in those conflicts, disputing the legitimacy of the de facto states and seeking to isolate their populations.

Realizing this reality, in 2018 the Assembly adopted its Resolution 2240 where it reaffirmed the legal obligations on Council of Europe member States to co-operate fully and in good faith with international human rights monitoring mechanisms, including in terms of access to conflict zones.

In addition, Secretary General Jagland in his 2019 report referred again to that challenge and presented his ideas of addressing it. In particular, he proposed that the “Commissioner for Human Rights should have a full, free and unrestricted access to all unresolved conflict zones, at any time, and by use of any possible and secure means of access”. However, there is no progress so far. It is not hard to guess the reasons…

Why do some member states oppose greater transparency when it comes to de facto states?

One of their fears is the risk of legitimization of authorities of de facto states. But, for instance, Resolution 2240 clearly states that visits to those territories and contacts with authorities do not constitute and should not be presented as recognition of those authorities’ legitimacy under international law. Such an approach, engagement without recognition, is widely and successfully used by the international community, for example, when interacting with the Palestinian Authorities and somewhat Kosovo. So, this fear is not very substantiated.

But more importantly, their goal is to maintain maximum isolation of the de facto states to prevent international contacts, to hinder their democratic, social and economic development, as well as, to hide massive human rights violations and restrictions exercised by those member states.

What can move the process forward?

In statutory terms, the Council of Europe has the mandate and power to make genuine political and diplomatic pressure on member states to respect their commitments and fully cooperate to ensure full, free and unrestricted access to conflict zones. But, in practical terms, when it comes to action, many member states are reluctant to support enforcement of those obligations.

For instance, the only obstacle for the Human Rights Commissioner’s visit to Nagorno-Karabakh is Azerbaijan’s opposition to such visits. It is important to stress that in terms of enabling physical access to unresolved conflict areas, the political will and consent of authorities of that de facto state is more relevant than of the member state. In that sense, the authorities of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh have stated that they are ready to fully cooperate with all relevant international organizations, including their human rights monitoring mechanisms. Perhaps it is the time for independent human rights institutions to put human rights protection before diplomatic and political expediency.

What should the international community do in de facto states?

I believe that the international community should not only monitor the human rights protection situation in de facto states but also contribute to its continuous improvement. Monitoring without contribution will be like to take school exams without continuous teaching, which cannot ensure efficiency.

I would divide the monitoring and contribution process into three dimensions: local, regional and international.

1. At the local dimension, they should monitor human rights violations possibly committed by the authorities, as well as, the compliance of institutions and mechanisms with international standards. Overall, it is the framework of Human Rights Ombudsman’s mandate. In our case, we have already built democratic institutions and human rights protection mechanisms, we regularly hold democratic elections, we have separation of powers, etc. However, we need further and faster development of our institutions and mechanisms, including consistent capacity building of state institutions and civil society. New reforms are needed in the spheres of some rights, including social-economic rights, torture prevention, rights of children, persons with disabilities, women etc. It is important to mention that we recognize our needs and have political will for addressing them. In that sense, human rights international monitoring bodies and non-governmental organizations can have their contribution by working in Nagorno-Karabakh.

2. At the regional dimension they should monitor the situation with human rights protection in the context of unresolved conflicts, where the main perpetrators of human rights violations are certain member states of the Council of Europe. In our case, the situation is probably the worst one, because Azerbaijan is a champion of human rights violations both domestically and externally. Unfortunately, the international community makes pressure and uses sanctions on Azerbaijan for domestic violations, but not for violations against the people of Nagorno-Karabakh. I’ll bring only a few examples of such violations.

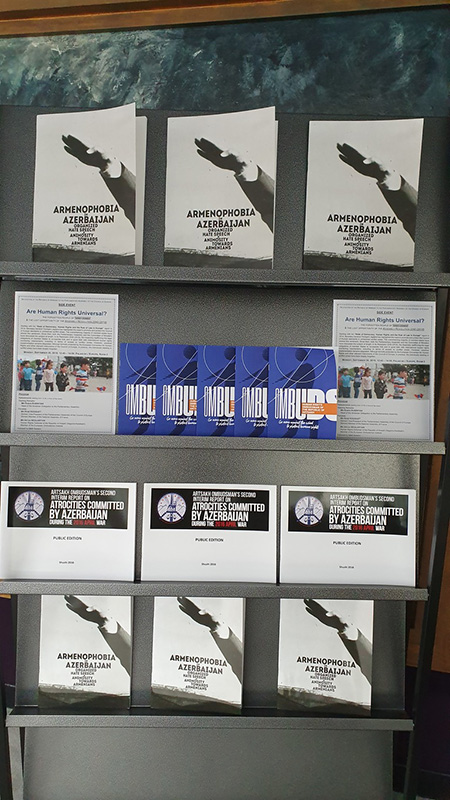

· Firstly, for decades Azerbaijani authorities conduct anti-Armenian hatred or Armenophobic state policy, which includes encouraging hating and killing Armenians, teaching at schools and kindergartens to hate Armenians, dehumanizing all Armenians, accusing Armenians of all their failures. An infamous example is the Safarov case, when an Azerbaijani officer axed an Armenian officer at a hotel in Budapest, when the latter was in sleep. He was extensively heroized in Azerbaijan, the President awarded him, and the Ombudsman stated that he is a bright example for the Azerbaijani youth. The details of the Armenophobic policy are presented in our 2018 report on Armenophobia in Azerbaijan.

· Secondly, Azerbaijan always uses bellicose rhetoric against Karabakh and Armenia threatening to go for war, which is a genuine threat to our lives and violates international law norms of prohibition of war. Moreover, in 2016 April, Azerbaijan lunched a war against Nagorno-Karabakh, involving tens of thousands of troops and special forces, heavy artillery and rocket systems, including those prohibited by international treaties. Almost all Karabakh civilians and combatants, who ended in the hands of the Azerbaijani armed forces, were tortured, executed or mutilated. 3 of them were beheaded in ISIS style. 3 civilians were killed and mutilated, including a 92-years-old lady. A kid was killed and 2 others were wounded as a result of shelling of a Karabakh school. Hundreds of persons had serious property damages because of Azerbaijani shelling, and thousands left their homes. To make sure that it was organized and encouraged by the state, let me inform you that after the war the Azerbaijani President Aliyev publically awarded some of crime perpetrators, including the soldier who beheaded 2 Armenian servicemen. Please note that though the international media largely covered all those events, but no international monitoring body came to Nagorno-Karabakh to assess the situation. These horrendous and barbaric crimes were committed by Azerbaijan, a Council of Europe state, against people of Nagorno-Karabakh, who are entitled to all protection provided by the European Convention of Human Rights.

· Thirdly, there are various human rights of Karabakh people which are continuously violated by Azerbaijan. For example, the Azerbaijani authorities stated that they would shoot down civilian airplanes if we operate the Stepanakert airport. Besides, it blacklists all the foreigners visiting Karabakh, even in some cases official Baku tried to prosecute them with criminal cases, but Interpol didn’t accept the Azerbaijani applications. They launched criminal cases against even 3 members of the European Parliament, but it was only a propaganda step, no serious legal basis and consequencies. Azerbaijan also makes political and diplomatic pressure on any international investor or company investing in Karabakh, any organization working in Karabakh, scientist having researches in Karabakh and so on. In all those cases, I think, different rights of our people are violated or restricted.

3. At the international dimension, the human rights of de facto states’ inhabitants are violated or restricted by the international community. In general, the largest manifestation is the isolation of de facto states from international programs and human rights protection systems. As a result, de facto states’ inhabitants have issues with getting visas, recognition of civil registration documents, recognition of educational documents etc. Those issues affect proper realization of wide range of human rights of the people abroad, including right to education, healthcare, social security, economic development, communication, free movement and so on.

Though the Karabakh case is unique, but other de facto states share some similarities with us in that sense.

Does the isolation mean the end of life in de facto states?

Lack of international recognition should have minimal impact on human rights protection, otherwise international organizations cannot have the absolute right to talk on human rights and its universality principle.

Isolation means only more struggle, more efforts and more reasons to value human rights, relying on your own potential. But, for sure, the life continues and develops there, even if they are perceived as “grey zones” for outsiders who don’t want to visit there.

However, regardless of that isolation, the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh has taken responsibility to participate in international life and to use the international standards to develop a stronger democracy, better protection of human rights and strengthening the rule of law. Karabakh has unilaterally joined and incorporated into its legal system a number of international human rights treaties, including:

· Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

· International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,

· International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,

· European Convention of Human Rights,

· Geneva Conventions and some other treaties.

· In addition, I recently officially proposed to the Government and the Parliament to join also the Convention on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which will improve the torture prevention mechanisms in the country.

Moreover, our Republic feels accountable to the international community and recently submitted its initial voluntary periodic report on implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to the UN. Nagorno-Karabakh also prepared its national review on implementation of the 2030 Sustainable Developments Goals. It means that we are open to cooperation and international monitoring mechanisms.

To sum up, the best way of exploring any country is to visit there. So, I would invite all of you to visit Karabakh to see with your own eyes the life, challenges and successes we have, to realize that all the people should be really equal, all the people deserve human rights protection and peace everywhere, whether they live in Strasbourg or in Karabakh.”

The Human Rights Defender’s Staff of the Artsakh Republic