In today’s Chamber judgment1 in the case of Nikolyan v. Armenia (application no. 74438/14) the

European Court of Human Rights held, unanimously, that there had been:

a violation of Article 6 § 1 (right of access to court) of the European Convention on Human Rights,

and

a violation of Article 8 (right to respect for private life).

The case concerned an applicant who was declared legally incapable in 2013, following proceedings

brought by his wife and son.

The Court found that the applicant could neither pursue his divorce and eviction claim against his

wife nor seek restoration of his legal capacity in court because Armenian law imposed a blanket ban

on direct access to the courts for those declared incapable. That situation had been exacerbated by

the fact that the authorities had appointed the applicant’s son as his legal guardian, despite their

having a conflictual relationship.

Read also

Moreover, the judgment depriving the applicant of his legal capacity had relied on just one,

out-dated psychiatric report, without analysing in any detail the degree of his mental disorder or

taking into account that he had no history of such illness.

Principal facts

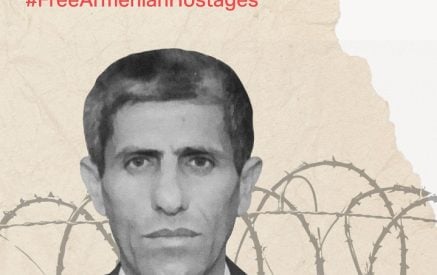

The applicant, Gurgen Nikolyan, is an Armenian national who was born in 1939 and lives in Yerevan.

In 2012 Mr Nikolyan lodged a divorce and eviction claim before the courts against his wife,

submitting that their conflictual relationship made co-habitation unbearable. However, the domestic

courts never examined his claim as he was declared legally incapable in 2013, following proceedings

brought by his wife and son, who was living with his family in the same flat.

In particular, in November 2013 the District Court declared Mr Nikolyan incapable, holding that he

had a mental disorder and was not able to understand his actions or control them. It based its

findings on a court-ordered psychiatric report of September 2012, as well as statements by his wife,

neighbours and a local police officer about overly suspicious, argumentative and at times aggressive

behaviour and absurd accusations against his wife.

Mr Nikolyan’s son, who had been appointed as his guardian during those proceedings, then

requested termination of the divorce and eviction proceedings. The District Court granted that

request in October 2014 on the grounds that domestic law authorised a guardian to withdraw the

claim of a person deprived of their legal capacity.

Mr Nikolyan, who was also in conflict with his son, had asked the local body of guardianship to take

into his account his opinion when appointing his guardian, to no avail. He went on to contest the

guardianship decision before the courts and the Court of Cassation, taking note of the applicant’s submissions on conflict of interest and regular disputes with his son, remitted the case. In 2017

those proceedings were still ongoing and their outcome is unknown.

He also made a number of unsuccessful attempts to restore his legal capacity, writing to the Minister

of Health and a psychiatric hospital and applying to the courts to review his state of health. In

particular, as a person deprived of his legal capacity, he was not allowed by the law in force at the

time to institute court proceedings.

Complaints, procedure and composition of the Court

Mr Nikolyan brought a number of complaints under Article 6 § 1 (right to a fair hearing/access to

court). In particular, he argued that after he had been declared legally incapable he had no standing

before the domestic courts to pursue his divorce and eviction claim or to apply for judicial review of

his legal incapacity. Also relying on Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life, the home,

and the correspondence), he complained that his being deprived of legal capacity had breached his

right to respect for his private life.

The application was lodged with the European Court of Human Rights on 13 November 2014.

Judgment was given by a Chamber of seven judges, composed as follows:

Ksenija Turković (Croatia), President,

Krzysztof Wojtyczek (Poland),

Armen Harutyunyan (Armenia),

Pere Pastor Vilanova (Andorra),

Pauliine Koskelo (Finland),

Jovan Ilievski (North Macedonia),

Raffaele Sabato (Italy),

and also Abel Campos, Section Registrar.

Decision of the Court

Article 6 (right to a fair trial/access to court)

The Court noted that Armenian law imposed a blanket ban on direct access to the courts for those

declared incapable, such as Mr Nikolyan. Such a blanket ban, which did not leave any room for

exception, was not in line with the general trend at European level.

The only proper and effective means to protect his legal interests before the courts had therefore

been through a conflict-free guardianship.

However, the body of guardianship had appointed Mr Nikolyan’s son as his legal guardian, despite

their having a conflictual relationship. The Court doubted that the son could be genuinely neutral

when representing his father in the divorce and eviction claim. Furthermore, the District Court had

not examined at all whether the son’s request to withdraw the claim had been in his father’s best

interests. Nor indeed had it provided any explanation for its decision to accept that request.

The authorities’ failure to ensure a conflict-free guardianship had further exacerbated Mr Nikolyan’s

situation, namely the fact that the blanket ban prevented him from directly seeking restoration of

his legal capacity with a court.

It therefore found that Mr Nikolyan’s lack of access to court in the divorce and eviction proceedings

and to seek restoration of his legal capacity had breached Article 6 § 1.

Article 8 (right to respect for private life)

The Court reiterated that national authorities’ decisions to deprive someone of their legal capacity

called for strict scrutiny, given the grave consequences for that person’s private life. In previous

cases it had held that fully depriving someone of their legal capacity had to be justified by a mental

disorder “of a kind or degree” warranting such a measure.

However, Armenian law did not provide for any such tailor-made response. It only distinguished

between full legal capacity or full legal incapacity. In particular, the judgment depriving Mr Nikolyan

of his legal capacity had relied on just one psychiatric report, which was 14 months old, without

analysing in any detail the degree of his incapacity. The report did not explain which actions exactly

the applicant had been incapable of understanding or controlling, nor did it observe any selfdestructive or grossly irresponsible behaviour or find that he had been unable to take care of

himself. Indeed, he had no history of mental illness and it was the first time that he had had a

psychiatric examination.

It concluded that depriving Mr Nikolyan of his legal capacity had been disproportionate to any

intended legitimate aim. His right to respect for his private life had therefore been restricted more

than had been strictly necessary, in breach of Article 8.

Article 41 (Just satisfaction)

The Court held that Armenia was to pay Mr Nikolyan 7,800 euros (EUR) in respect of non-pecuniary

damage.

The European Court of Human Rights