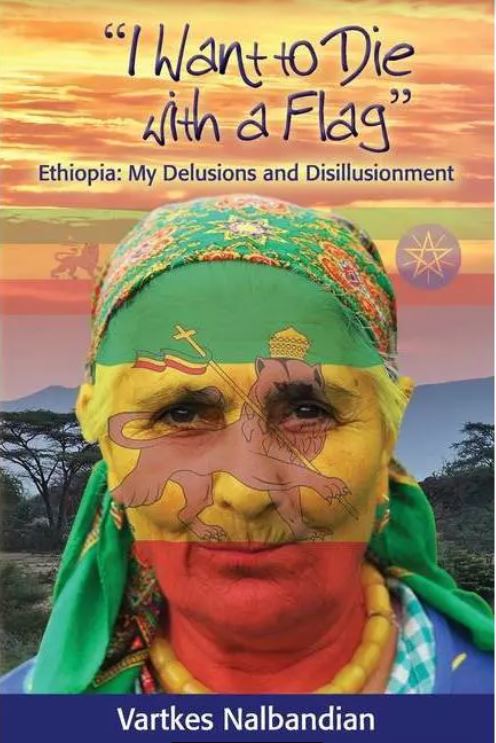

The Armenian Weekly. Ethiopia: My Delusions and Disillusionment

This brave and outspoken account of life under different regimes in Ethiopia is Vartkes Nalbandian’s memoir of those years. It is not a novel, nor is it a ‘history of the Armenians of Ethiopia’ although they do feature.

Vartkes’ family and his early life, his heroic attempts to preserve the vestiges of the once vibrant Armenian community of Ethiopia, and his years of attempting to do business under three destructive regimes following the revolution of 1974 are all well described. It contrasts well the relatively benevolent and ordered imperial days with the descent into chaos after revolution. It is a story of resilience and survival.

For those of us who left the country at the beginning of its Marxist travails, Vartkes’ accounts of life under the terrifying Derg Regime, and later the various iterations of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)-led Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF)—marginally less terrifying, but equally corrupt and arbitrary—give insight to the horrors and daily tribulations others can only imagine. Those who think that living through those times in Ethiopia as an Armenian and making a living was an easy task, should pay good attention to the later half of the book.

Vartkes has a good turn of phrase—sometimes sarcastic which is understandable. Each of his chapters ends with a rhetorical question. As he says again and again, he ‘could write whole chapters’ on certain subjects—and I really urge him to do so.

The book starts off—as the title suggests—with an exploration and description of what it is to be stateless in a country in which you were born, in which you worked and in which you raised a family. There are also the petty discriminations of being an ‘other,’ and the greater institutional discriminations because your name does not conform to the norm, and/or you are perceived to have been privileged. It was a systematic denial of citizenship which touched almost every Armenian family in Ethiopia. This did not merely mean that you could not obtain a passport to travel, but that you might not be able to attend university in the country of your birth. Vartkes writes that he was turned down by Haile Selassie I University twice, necessitating him to take up his studies in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Armenia.

The constant fight to overcome discrimination, envy and obstruction in various ministries, the bureaucratic red-tape involved, is well described. Even towards the end of the book when he documents his business dealings with government officials who seem to be there just to obfuscate and deter, Vartkes remains resilient enough to try and try again. Hence the subtitle ‘Ethiopia: My Delusions and Disillusionment.’

Vartkes laments, as all Ethio-Armenians do, the relegation, or rather, the expunging of Armenians from Ethiopian history. As he says, the country’s history is written and rewritten with the advent of each regime. Now, the presence of Armenians is being physically expunged from Addis Ababa by the simple expediency of modernization—that is, the pulling down of almost every old building in the city. Vartkes writes of the vandalism of the Midroc Group which, instead of renovating and preserving the landmark building, blew up the Grand Hotel overlooking Lake Hora—a much beloved recreation place for all, once owned by Paylag Yazedjian—upon acquisition. Much of the pre-Second World War architecture and town planning was owed to two Armenians, Krikor Hovian and Minas Kherbekian, whose names have all but disappeared from history books.

There is, rightly, much about the various choirs in Addis Ababa, and even the Glee Club at the university, all founded and conducted by Nerses Nalbandian, Vartkes’ father. For while Nerses’ uncle, Kevork Nalbandian, had written the music for the National Anthem of Imperial Ethiopia, Nerses wrote anthems for many of its institutions. Towards the end, Nerses was asked to write the anthem for the opening ceremony of the OAU (Organization of African Unity). However, bizarrely, officials required him to conduct the choir from behind a curtain and have an ‘ethnic’ Ethiopian mimic his gestures.

There is much heartache in this story. Not least in Vartkes’ and the tiny community’s striving to keep the Armenian church, school and club open. Not only because of the grasping Marxist regime nationalizations, but also from Armenian institutions such as the AGBU and Etchmiadzin. As deacon, he has managed to keep Sourp Kevork church open and has officiated at more than 100 funerals. It is understandable that he feels undervalued. His account of Catholicos Karekin II’s visit in 2000 at the invitation of His Holiness Abune Paulos, Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and the Catholicos’ ungraciousness, made my head spin. Vartkes’ outrage is absolutely justified.

I finished the book feeling that many of the descriptions of daily life would not have been too out of place if written during the Reign of Terror in France, or during the first years of the Russian Revolution, or during Stalin’s regime in the Soviet Republics. Through all the terror and struggles, life goes on, and there is only hope that something better will turn up.

As a self-described ‘custodian of Ethio-Armenian history,’ Vartkes has offered a brief but enticing view of what a book about them could be. I for one, cannot wait to read it.

Vartkes Nalbandian