The Armenian Weekly. NEW BRITAIN, Conn.— When Ardemis arrived in New Britain, Conn., as a 15-year-old orphan of the Armenian Genocide, she immediately set about putting her life in order. The Hairenik, a prominent newspaper that served the newly-arrived Armenian community of the US, helped.

Ardemis was a mature woman, aged beyond her 15 years. And she had the maturity to understand that she wanted to remain grounded in her culture. So she read the Hairenik.

The Hairenik was an Armenian-language daily newspaper in the 1920s when Ardemis first started to read it. And the paper remained a daily for all but a few years of her long life. Today it is published weekly.

For Ardemis’ entire life, the Hairenik was her lifeline to the past. The paper was delivered by mail to her home. And each paper filled Ardemis’ life and helped her connect to the Armenian community.

Read also

I know this because I saw it with my own eyes, years after Ardemis had grown old and had become my grandmother.

My childhood home was just three miles from the home of Grandma Ardemis in New Britain. I used to ride my bicycle to visit her—once I was old enough and brave enough to venture such a great distance on two wheels.

And so, as a ten-year-old, I would sometimes arrive unannounced at Grandma’s home on a summer afternoon. I recall being ushered into the kitchen—the heart and nerve center of her home. There I caught a glimpse of Grandma Ardemis’ secret life.

This secret life, I discovered, involved preparing Armenian food. There was always something cooking on the stove, or baking in the oven, or ripening on the counter. One day, Grandma Ardemis was stuffing grape leaves with meat. The next, she was rolling dough for pakhlava. And on occasion, the whole house would be turned into a tomato cannery.

Today when I recall Grandma Ardemis, I also recall the smell of anoush abour simmering on her stove, that delightful sweet soup of apricots, prunes and raisins. And I recall that as the anoush abour was simmering or as the paghlava was baking, Grandma Ardemis would inevitably be poring over the Hairenik.

The Hairenik was a huge broadsheet newspaper back then. Ardemis would fold it open so that it covered the entire kitchen table as if it were a tablecloth.

And that’s where the paper would stay all day.

Ardemis did not read the Hairenik casually.

No, she would lean in, her eyes just inches from that huge page of gray type. And she didn’t rush the paper, either. Ardemis turned the page only after she had read every line. By evening, when she had finished reading and after her eyes had grown weary, she would fold up the paper and wait for the next day’s news.

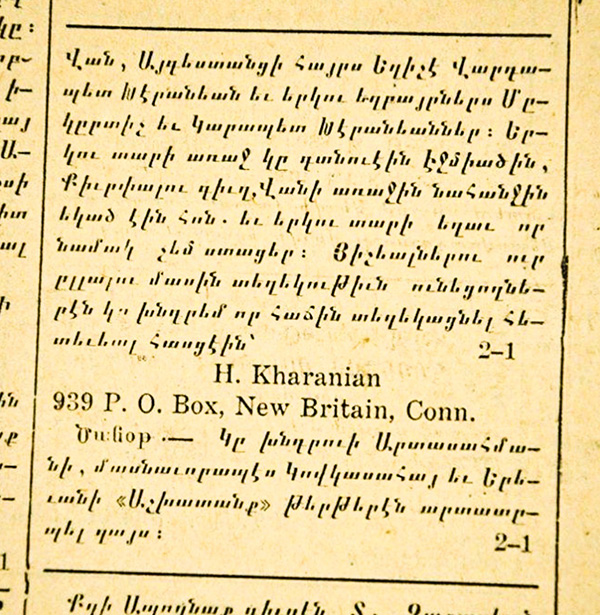

Classified advertisement from the April 22, 1919 edition of the Hairenik newspaper. The notice seeks information about family members of Hovhannes Kharanian (Karanian) who were “lost” during the Genocide.

Fifty years earlier, if she had read the April 22, 1919 edition of the Hairenik—and it’s reasonable to expect that she did— she would have seen a classified advertisement from a teenaged boy from Van named Hovhannes Kharanian (Karanian). This advertisement, like so many others in the Hairenik at the time, sought information about family members who had been “lost” during the Genocide. She and Hovhannes would marry soon afterward.

I shared these memories with my mother recently.

My mom was born Agnes Barsoian in Pawtucket, Rhode Island nearly a century ago.

Shortly after WWII she got married, and in quick succession she changed her name to Agnes Barsoian Karanian and moved to New Britain, Conn. to start a family. And right about the same time, she also started a subscription to the English language newspaper that is today known as the Armenian Weekly—the English language counterpart of the Hairenik. She’s been a reader of the Weekly her entire adult life.

The Weekly is a tabloid, and not a broadsheet. So Mom reads the paper while sitting in her favorite chair, instead of at the kitchen table.

It occurred to me recently while sitting with my Mom as she read the freshly delivered edition of the Armenian Weekly, that she might be the owner of the oldest and longest uninterrupted subscription of the paper.

“Mom,” I asked, “how long have you subscribed to the Weekly?”

“I don’t know. I’ve always subscribed,” she told me.

“Do you recall ever not subscribing?”

“Well, I don’t think I subscribed before I was married.”

My parents were married after the war in 1948.

By my best estimate, my mom has subscribed to the Weekly continuously since then—for about 70 years. She’s been a subscriber for so long, that even the Weekly has lost or deleted the records.

The assistant editor of the Weekly told me recently that yes, Agnes Karanian is a subscriber. When did she start, I asked. The Weekly’s records don’t go back that far, I was told. Between Agnes and her mother-in-law—my Grandma Ardemis—these two matriarchs have subscribed without interruption for a century.

Mom enjoys reading coverage of local Armenian events—community news that is a specialty of the Weekly. To this day, she particularly enjoys reading about the annual sporting event hosted each year on Labor Day weekend by the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF), an event that is known as the AYF Olympics. Never mind that Agnes hasn’t attended one of those events since, well, a long time.

In 1946, Mom had been a spectator at the AYF Olympics in New Britain. She was young. She was single. She and her girlfriends had traveled from Pawtucket for the event, but only after they had each enlisted the support of chaperones and had secured special permission from their parents. While at the Olympics, Agnes met a young man from New Britain named Henry Karanian.

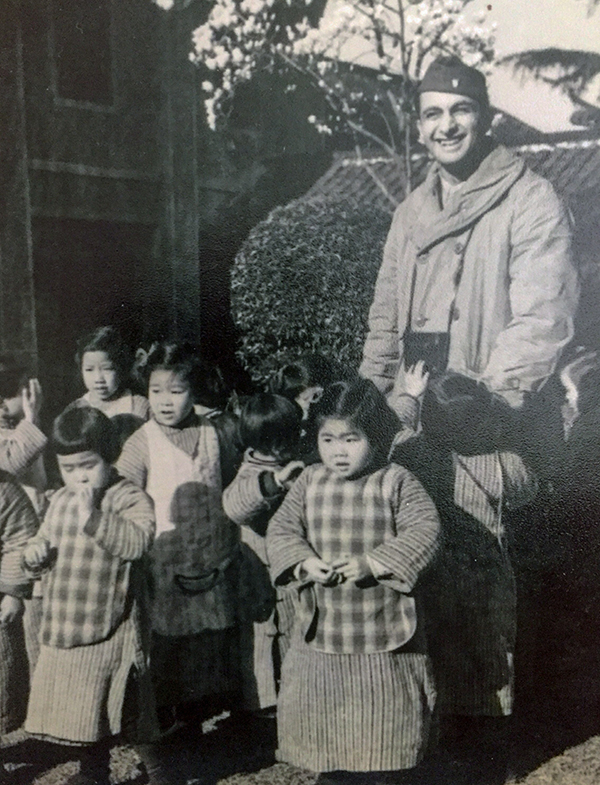

Henry had a camera—the same camera he had with him while he was stationed in Shanghai during the war. Now that he was home, he spent time in his dark room, processing those photographs. Photography was an uncommon hobby at the time. This proved to be an asset to Henry. His camera and his outgoing personality introduced Henry to many new Armenian friends. At the Olympics, he photographed the spectators, including Agnes. As he had done with each of the other portraits he took, he offered to mail the photograph to her. All Agnes needed to do was give Henry her name and address.

Henry Karanian with a group of children in Shanghai during WWII. Henry served in the US Army Air Force and enjoyed making photographs whenever he could. A child appears to be reaching for his camera.

They were married less than two years later.

Agnes recalls these events frequently, especially during the annual release of the special AYF Olympics Issue.

Lately, my mom has been receiving two copies of the Weekly in the mail. One is English, the second is in Armenian.

My mom delights in the bonus issue. “Have you noticed that they’ve started sending me the paper in Armenian, too?” she asked me. “How do they know that I can read Armenian?”

Indeed, I agree. How do they know? Perhaps this is more proof that the Armenian Weekly knows a great deal about our community.

Main photo. Agnes Karanian, lifelong reader of the Armenian Weekly, at her home in Connecticut.