The Armenian Weekly. Last week, the Public Services Regulatory Commission (PSRC)—Armenia’s equivalent to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)—circulated an early draft of a bill which would empower internet service providers (ISPs) to engage in bulk collection and storage of user data. While the PSRC has offered a relatively benign explanation for the move, stating that it’s only intended to clarify legislation on data management, the proposed bill contains language that compels ISPs to collect and store identifiable information on anonymous online users. This includes datasets pertaining to emails, browser histories and the device used to access the internet.

The PSRC has contended that it is already authorized to collect user data, which would not be accessible to authorities without a warrant. Still, this flagrantly Orwellian attempted government overreach into the private lives of its citizens should be alarming to any privacy rights advocate and stands in sharp contrast to the authorities’ commitment to an open and transparent society.

Aside from the more mundane issues such as the lack of a good explanation for this law’s necessity or the large costs incurred on smaller ISPs who will have to pay out of pocket to secure the extra storage space, the PSRC’s actions raise some serious questions on the limits of the state’s regulatory authority.

Armenia’s 2006 Law on Electronic Communication authorizes the PSRC to regulate telecom in the country, including internet access, though there are absolutely no legally established term limits on the agency’s leadership, nor is there any effective protocol in place to replace it. Most troubling is the lack of clarity on whether the PSRC’s proposed actions are even constitutional.

Read also

As civil libertarians have pointed out, the bill would be in violation of a number of Armenian laws designed to protect individual privacy. The Protection of Personal Data law, which survived former President Serzh Sargsyan’s 2015 constitutional amendment untouched, strictly limits the government’s ability to collect and store personal data without their consent. The current law also explicitly prevents the collection of “any kind of data which makes possible directly or indirectly identify an individual” without a warrant.

Ashkhen Kazaryan, director of civil liberties at the Washington, DC-based watchdog TechFreedom, warns that if adopted, the ISP regulation bill would “turn Armenia into one of the biggest surveillance states in the region.” Echoing the objections of many critics in Armenia, she characterized the bulk collection of user data without rigorous due process in a court system that hasn’t been fully freed of corruption as “outlandish,” adding (at her insistence), “What is this, North Korea?”

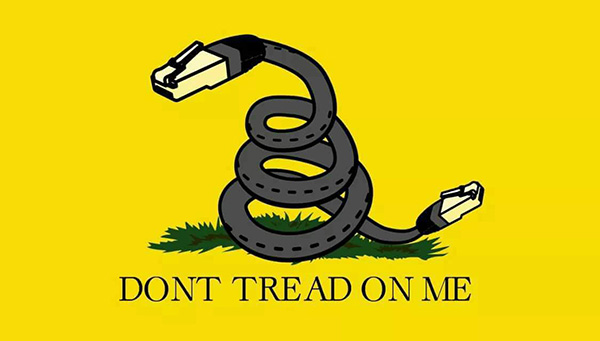

Armenians have long counted the freedom to privately access the internet among the country’s most prized civic virtues. The open and decentralized nature of Armenia’s ISPs has been credited with facilitating the growth of a vibrant and resilient civil society, despite the semi-authoritarian governments of the past.

While there is no doubt that the new Armenian authorities have made substantial achievements in promoting government accountability, transparency and civilian oversight into its various agencies, the state does have a not-insignificant history of meddling with the country’s access to the internet. In 2016, many users in Armenia reported being unable to access social media sites like Facebook through major ISPs Armentel or Ucom for a 40-minute long period which coincided with the start of the Sasna Dzrer’s assault on the Martuni police depot. Facebook later confirmed that it had been blocked from within Armenia.

According to Freedom House, Armenian authorities have also been known to occasionally block content deemed pornographic or criminal in nature in accordance with Article 263 of the criminal code. Activists and journalists have also reported being blocked in what regulators later admitted to being poor attempts at tackling hate speech on the web.

Recent events have demonstrated that even citizens of more mature democracies with boisterous legal, democratic and civic institutions have not been immune to covert mass surveillance operations on the part of their own intelligence apparatus outside of legal purview. Armenia’s 2015 Protection of Personal Data law placed the country in line with European standards with respect to the processing of personal data. As the EU moves ahead with legislation to protect users’ “right to be forgotten,” this proposed bill would move Armenia in the opposite direction.

Robust, free and unregulated internet access is the foundation upon which Armenia is building its credentials as a democratic society as well as its much-lauded tech industry. While the need to better define the state’s regulatory responsibility is not in question, haphazard government intervention on the web may set a dangerous precedent for the future development of Armenian civil society as well as the country’s attractiveness as an international technology hub. Armenia’s state telecom regulator has enjoyed a reputation as one of the country’s most independent and transparent agencies for over a decade, so why the sudden change in attitude? As Kazaryan concludes, “New Armenian government should know better.”