ԵՌԱԳՈՅՆ

By Aleen Arslanian

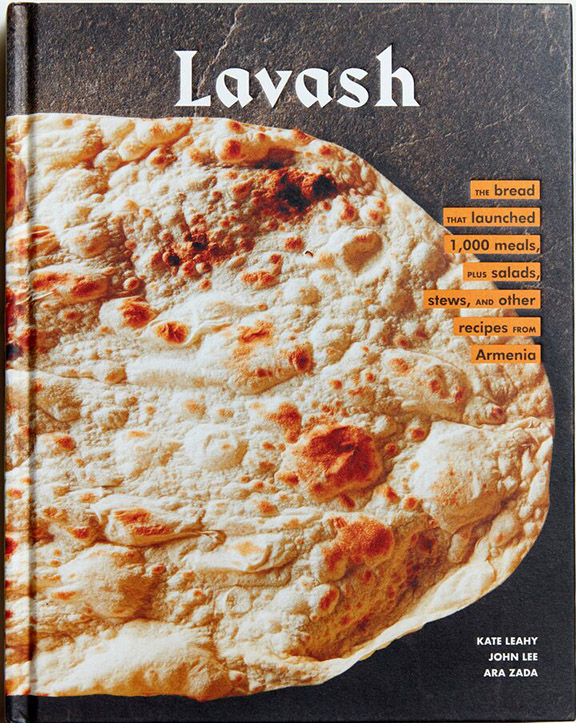

“Lavash,” an Armenian cookbook that is the first of its kind, officially launched last month. Co-authored by Kate Leahy, John Lee, and Ara Zada, the part cookbook, part travelogue takes readers through various villages in Armenia, and Artsakh, while showcasing a multitude of foods that are made by Armenian natives. From Goris to Gyumri, the cookbook features phenomenal photographs of villagers, villages, and the foods that make Armenia the country it is today. “Lavash” highlights the most common dishes that are made in Armenia, including soups, stews, vegetables, meats, and desserts, while being careful not to lay claim to any of the recipes as Ancient Armenian, or of Armenian origin. As Zada noted, “This is what they’re eating in Armenia, now.”

It all began in the summer of 2015, when Lee was invited to teach a food photography class at TUMO, Yerevan. During his three weeks in Armenia, Lee fell in love with the country. “The country, the people, the food…there was something really comforting about it,” he said. Three days after his return from Armenia, Lee was on a flight to Myanmar, Burma, where he would photograph foods on a project titled, “Burma Superstar: Addictive Recipes from the Crossroads of Southern Asia.” During his flight to Burma, he was seated next to Kate Leahy, a cook and cookbook author, who he’d be working on the project with. Coincidentally, Leahy had some background in Armenian food.

While pursuing her undergraduate degree at the University of California, Davis, Leahy worked on a project titled, “Cookbooks and Armenian-American Identity” – a best-seller. However, this was not her first encounter with Armenians, as she had a few Armenian-American friends in college, who she describes as seeming “to know and care so much more about food” than her non-Armenian friends. Years later, Leahy unintentionally dove back into the world of Armenian cuisine when she met Lee on their flight to Myanmar. During the 12-hour flight, Lee would go on to show Leahy the colorful foods he photographed while teaching at TUMO. She remembers looking at the photos and thinking that they looked “like they belonged in a cookbook.”

Read also

Shortly after completing their project in Burma, CEO of TUMO Marie Lou Papazian, who knew that Lee and Leahy were interesting in publishing an Armenian cookbook, linked the two with Ara Zada, a chef based in Los Angeles who had been invited to teach a cooking class at TUMO. Papazian flew down to Los Angeles to meet Zada, with Lee, in hopes of bringing this unique idea to fruition. Having grown up in an Egyptian-Armenian household, cooking Armenian food is second-nature to a chef like Zada, and he was more than willing to contribute to the project. After discussing the prospects of the cookbook over dinner at Carousel in Glendale, the decision was made: Leahy, Lee, and Zada would create an equal-part, co-authored Armenian cookbook.

“As a complete outsider, I didn’t know the difference between Western and Eastern Armenian, originally, when I first went to Armenia. To me, it was just yummy food. Then I go back to San Francisco, and I’m looking for the food I was eating in Armenia – I couldn’t find it. There was even a local Armenian church in my neighborhood in SF that had one of those food festival weekends. I went looking for Armenian food, and there was nothing. It was just pan-Mediterranean food. I was kind of disappointed. That got me thinking more about what the differences between the food that’s found within Armenia – between its geographical borders – verses the food that’s found in the Diaspora,” said Lee.

A cookbook four years in the making, the co-authors of “Lavash” traveled to Armenia to meet with villagers, gather recipes, and document their journey. Throughout their stay, they were accompanied by an interpreter who helped translate recipes, as well as conversations, between the authors and the villagers. Zada, who speaks Western Armenian, and Leahy and Lee, who describe themselves as “full-blow odars,” needed a translator in order to precisely interpret recipes. After renting a car and getting situated with a translator, Leahy, Lee, and Zada spent three weeks exploring different Armenian villages, including Yerevan, Argel, Areni, Goris, Stepanakert, Sevan, Dilijan, Alaverdi, and Gyumri. With the guidance of TUMO, the three authors visited specific villages in hopes of finding the recipes they were in search of.

When Zada first visited Armenia five years ago, he was looking for the foods that were made in his Diasporan Armenian home. “There’s a serious gap between Westerners and Easterners, and what they’re eating in Armenia verses what everyone thinks is Armenian.” He explained how Armenian food in the Diaspora is heavily influence by its surrounding environment – each Diasporan community has their own way of making certain foods. However, the authors of “Lavash” wanted to write an Armenian cookbook, featuring foods made and enjoyed in Armenia today. They realized that the only way to authentically create such a cookbook would be to travel to Armenia.

Walking into a village, “families will greet you with open arms. They don’t know you. You’re not even supposed to be there, but they open their doors to you. They will serve you everything that they have. They’re very hospitable,” said Zada, when describing their many interactions with Armenian villagers. “Everywhere we went they greeted us with open arms. They’d set massive tables. They would want us to stay the night. It was ongoing, everywhere we went.”

Prior to traveling to Armenia, the co-authors compiled a list of recipes, comprised of foods Lee had documented on his first trip to Armenia. Lee then had to reach out to individuals at TUMO, with whom he had both worked with and taught, in order to correctly identify the dishes he had photographed, as even Zada was unable to recognize them. Using this method, they assembled a long list of target recipes. However, when they arrived in Armenia, about 80 percent of those recipes changed.

When asked how they chose which dishes to include in the cookbook, Leahy explained that they “had to draw the line at certain things that were too specific, even if it was very popular in Armenia.” Although both khinkali and khachapouri are popular in Armenia, they are excluded from the cookbook, because they’re distinctly Georgian dishes. For Zada, a recipe that he wanted to include, but knew he couldn’t, was mante. While teaching a cooking class at TUMO five years ago, Zada realized that mante was a Diasporan food when only two out of seven students knew what it was. “But, now there’s mante everywhere,” said Lee, while describing the influx of Syrian Armenians to Armenia. “I’m interested in the topic more from a cultural-anthropological-sociological look at migration and the way that foods evolve over time. What’s great about this book is that it’s like a time-capsule of what Armenian food is like in 2018. Knowing that Syrian Armenians that fled Syria are s tarting to populate Yerevan, you start to get Syrian inspired foods. Chikufte is becoming a thing now. I’m thoroughly fascinated to see what’s going to happen in the next five years with the food that’s going into Armenia.”

The co-authors of “Lavash” wanted, more than anything, for the recipes to be accessible to everyone. “The idea was to be able to make food with ingredients you can get from Whole Foods, or Gelsons, or Vons – local,” said Lee. Easily accessible recipes in the book include tjvjik, banirkash, tatar boraki, and salatta vinaigrette. “We wanted this to be a book people could cook out of. Not just a book of collection of recipes from Armenia, but a book of collection of recipes that people could use,” said Leahy, as they attempted to name each of the 22 herbs and greens needed to make Zhingylov hats, a traditional Artsakh dish. Although the recipe calls for 22 herbs and greens, the co-authors explained that many of the Armenian villagers use less than 22, as they forage for most of their greens. “We’d see ladies foraging on the side of the road. We pulled over a few times to ask what they were picking. They would find one leaf at a time, eventually picking handfuls,” said Zada.

There were certain ingredients that the co-authors found were lost in translation, like those used to make “Poison Ivy” soup. During his first trip to Armenia in 2015, Lee and his students visited Tufenkian in Dilijan. While in Dilijan, the group ate at a restaurant where the cooks were boiling greens and turning them into soup. When he asked his translator what the greens were, Lee was told they were poison ivy. After relaying the news to Leahy and Zada, the three could not wait to visit Armenia and try this daring soup together. However, when they arrived, they realized what they were told was poison ivy was actually stinging nettles.

“There was a lot of dissecting recipes. The Armenian words for the Armenians, and the Armenian names, are nowhere to be found. So, it’s difficult. Aveluk, for example. Aveluk is a green, that’s very common – google it, it’s sorrel. It’s not sorrel, but everything says sorrel. They braid it while it’ fresh, then they dry it, then they rehydrate it. They make salads out of it – salad with yogurt – and also soup. Very, very common everywhere [in Armenia]. Nowhere to be found out here,” said Zada.

A highlight of their trip to Armenia was Gayanei Mot, a restaurant in Yerevan which was owned and run by a woman named Gayane, who passed away last year. Although there are other, more well-known restaurants, Gayanei Mot sits close to the co-authors’ hearts. Ganyane’s restaurant has no signs indicating its existence. When Zada was first introduced to it, he was told they didn’t have menus, “You just walk in and they serve you what they have. It looked like somebody’s living room.” Gayane, who had created an incredibly “home-y” environment, would keep her regulars entertained by jumping on the piano and singing for them.

“It was like a true Soviet Armenian experience, to go there. You can kind of get a snapshot of what it looked like back in the day,” said Leahy, while recounting her own experience at Gayane’s. The co-authors also mentioned that Gayanei Mot was featured on Anthony Bourdain’s “Parts Unknown,” an American travel and food show. Following the passing of Gayane, a close friend of hers took over the restaurant. Although he is giving the restaurant life, the three agreed that Gayane was the heart and soul of the restaurant.

For Lee, an interesting detail of his “Lavash” experience – aside from all the wonderful foods – was unintentionally joining an anti-Sarkissian riot in April of 2018, when the co-authors traveled to Armenia to research recipes. During their visit, they were faced with the unexpected – the country was in the midst of a revolution. On Sunday, April 22, Lee had made plans to visit Geghard Monastery when he was confronted by a large, angry crowd in Yerevan’s Republic Square. He would soon find out that Nikol Pashinyan was meeting with Armenia’s Prime Minister at the time, Serzh Sarkissian. Lee watched, and photographed, as Pashinyan and company exited the Marriott Hotel with their fists raised in protest. He marched with the crowd from the Republic Square to Erebuni, photographing the scenes along the way. The protests ended with Pashinyan’s arrest, and Lee being hit by a police flash grenade. He was rushed to the hospital, where pieces of shrapnel were removed from his legs and stitches were applied.

“Lavash” is available for purchase at: Amazon, Barnes and Nobles, Indiebound, Waterstones (U.K.), Indigo (Canada), and TUMO (Armenia), Abril Bookstore, and Now Serving. The “Lavash” book tour ran from October 24 to November 19, and included stops in California: San Francisco, Orinda, Glendale, Los Angeles; Montreal, Canada; Massachusetts: Cambridge, Belmont; Washington, D.C.; and Seattle, Washington.

Main photo: “Lavash” is available for purchase at Barnes and Noble, Abril Bookstore, and Amazon