ԵՌԱԳՈՅՆ

By Gus Gomez

Singapore visitors are—with good reason—impressed by the marvelous architecture of the Raffles Hotel and many other prominent buildings in this island nation located at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, which includes Malaysia and portions of Thailand and Myanmar.

A more in-depth look at Singapore’s history also reveals a history of civic and commercial involvement by Armenian merchants and entrepreneurs who helped to develop this Asian hub in earlier times. This history is memorialized in part by the existence of Armenian Street in the central district of Singapore.

Some, guided by a spirit of travel and adventure, have come upon this jewel of knowledge entirely by chance—as compared to scholars in search of a better understanding of history.

Read also

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is a nation in Southeast Asia founded in the 1960s. It is, in fact, one large island in addition to several dozen smaller islets. Today, it is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in Asia, with a population just over 5 million.

The country emerged as a sovereign nation in 1965, following its separation from Malaysia. In modern times, Singapore served as a trading post under the control of the British with the arrival of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles in the early 1800s, later followed by occupation by Japan during World War II.

Singapore gained independence from Great Britain in 1963 along with Malaysia. Its history reveals it was once known as Singa Pura, meaning Lion City.

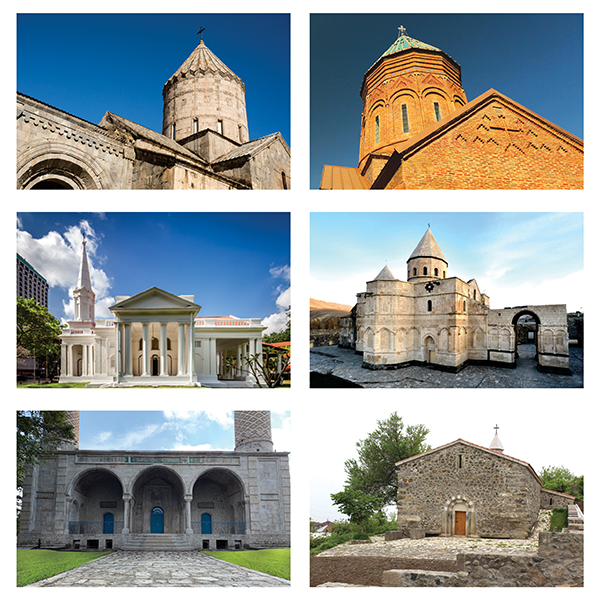

Armenian Street in Singapore first opened as Armenian Church Street sometime after the construction of the Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator. The street is essentially tucked between Coleman Street and Stamford Road near what is now one of the largest financial districts in the world.

Today, the street serves primarily as a pedestrian mall with store facades featuring galleries, restaurants, and other attractions adjacent to the Singapore Art Museum. Singapore Management University School of Law is located at the northeast end of the street, housed in a modern sleek structure just east of the Singapore River and Fort Canning, famous for Raffles House and Fort Canning lighthouse.

The Armenian population in Singapore is described as a small community with a significant presence in the early history of Singapore, numbering about 100 individuals at their peak in the 1920s, according to Wikipedia. They were among the earliest merchants to arrive when Singapore was established as a trading post by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles.

The first Armenian settlers in Singapore were descendants of Armenian people who migrated from Persia to other places including India and the Malay Peninsula. In the early 1800s, Armenian trading firms like Sarkies and Moses became more prominent in Singapore’s economy. Armenian merchants began investing in land by the 1830s.

One merchant, Catchick Moses co-founded the Straits Times (named after the Singapore Straits, the narrow ocean waters which separate Singapore from Indonesia). The newspaper went on to become the most prominent English language newspaper in Singapore.

Later, Agnes Joaquim cultivated a hybrid orchid flower which eventually became the national flower of Singapore, the Vanda Miss Joaquim. Her younger brother became a respected lawyer and served as president of the Municipal Commission, Singapore’s town council.

In the 1880s, the Sarkies brothers—Martin, Tigran, Aviet, and Arshak—founded the Raffles Hotel (named after Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles). The colonial-style hotel is one of the most famous hotels in the world. Today the hotel’s main entrance still opens to Beach Road—what used to be a quieter street along the seashore but is now a busy shopping area along with other luxury hotels in Singapore.

Over the years, the grandest balls and banquets were hosted at Raffles, according to Australian author and historian Nadia Wright, who is of Armenian descent. In fact, for a short time at the turn of the 20th century, the three major hotels in Singapore were owned or managed by Armenians.

In total, about 830 Armenians lived in Singapore between 1820 and 2000, as noted in Wright’s book, “Respected Citizens: The History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia.” The Armenian community virtually disappeared by the 1970s. But the small Armenian diaspora’s contribution to business and cultural endeavors was significant.

Armenian Street is of further cultural significance in Singapore, which includes other thoroughfares representative of the ethnic, cultural, and spiritual diversity of this country. The Sultan Mosque, for example, is located at the end of Arab Street.

As author Nadia Wright points out, every municipality has street names peculiar or unique to its history and culture. In Singapore, Armenian Street brings this point home, even as the city has transformed into a vibrant financial center in Asia.

Gus Gomez is a former mayor and councilmember in Glendale and is now a Los Angeles Superior Court Judge. He recently visited Singapore and came upon Armenian Street while exploring the city.