The Armenian Weekly. The difficulties specific to nursing homes in the current pandemic have been in the news recently and usually focus on the fatalities due to the virus. Yet these facilities have been entrusted with the care of our most vulnerable and revered family members, our parents, our grandparents, our aunts and uncles. Mary Beth Lescault, owner and director of nursing at The Cove at Grace Barker in Warren, RI wants to reassure family members that, “This is an environment where if you want to see true empathy and dedication and heroism, if I may, this is it. These people every day come in and do what they have to be doing. They are caregiver, they’re family member, they’re friend, they’re confidante, they’re support, they’re shoulder to cry on even though we can’t get close to do that.”

The personal nature of caring for our frail elders and the priority of that care are the overriding sentiments of everyone who spoke with the Weekly recently about their motivation and commitment in the field, including those in skilled nursing facilities, under hospice care, and participating in programs that allow them to remain in their homes.

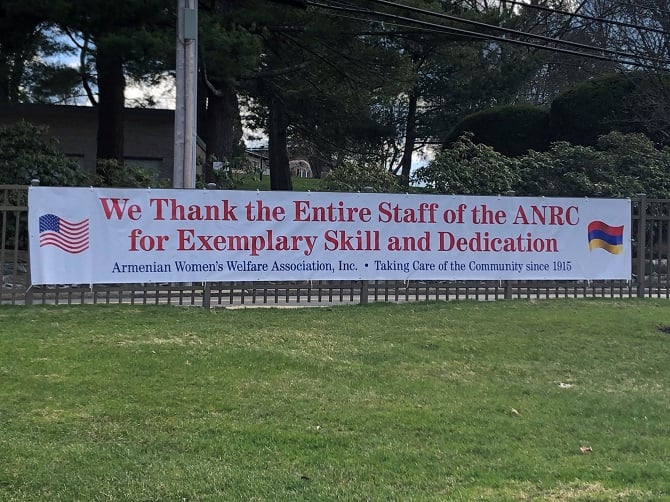

“It’s very personal to us,” said Stewart Goff, RN, MS, the CEO of the Armenian Nursing and Rehabilitation Center (ANRC) in Jamaica Plain, Mass., where about one-third of the resident population is Armenian. Goff’s wife Carolyn is Armenian, and her grandmother Arousiag Kharibian was a member of the Armenian Women’s Welfare Association (AWWA) which owns and operates the center. Those family relationships contributed to his appreciation of Armenian culture and history.

At the Armenian facility, it was the collective view of the staff that COVID-19 was inevitably going to get into the building. “In a disaster, you have to shed the rules you normally follow,” said Goff, who noted that crisis situations are nothing new for him. He led his staff in immediate preparations, restricting visitors and creating an isolation wing that has grown from eight beds to 20 on the second floor of the facility. Staff members were screened for fevers and other possible symptoms at a single entrance; they were also instructed on how to manage infection control standards and set up an effective system for distribution of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Read also

Ultimately, COVID-19 did enter the facility through a food service worker who showed no symptoms in the morning but had a fever midday and eventually tested positive. According to Goff, it was just three days after that when fevers began emerging in residents at the nursing center.

Early in the crisis, Goff instituted a weekly email update to family members of the residents in order to keep them informed and help reduce an influx of calls. His wife Carolyn is voluntarily managing the HelpLine, and ANRC Board President Susan Deranian is volunteering several days a week in full PPE, placing FaceTime and Skype calls between family members and residents.

As of April 13, the ANRC has had five deaths, three of which are considered COVID-specific, and two of which involved residents who were already quite ill. All had tested positive. Goff felt it important to note that the center would typically experience two to seven deaths monthly pre-pandemic. When it comes to the necessary supplies to continue fighting the crisis, Goff expressed that it’s a continuing challenge, but the community has come together to help, particularly with PPE. For instance, St. Stephen’s Armenian Apostolic Church in Watertown has shared all the gloves they had on hand.

With regard to how the staff are coping, Goff said, “We all have a weariness, but we all, I think, are feeling an exhilaration by seeing the way each of us is stepping up.” Goff explained that taking the long view of the crisis is important for everyone, including the family members of loved ones at the ANRC. “I’m hopeful that it will feel less of a disaster after 12 weeks, so six weeks from now, I’m hopeful we don’t feel in this emergency mode.”

One person on the front lines of caring for the elderly during this critical time is Karine Birazian Shnorhokian, MSN, RN, who has been the Regional Case Manager of Clinical Representation for Care One New Jersey for a little over a year, but it goes much further than that. When the crisis began, she immediately volunteered to serve on Care One’s COVID-19 task force, placing herself directly on the front line of the Care One facilities’ response to the virus. The Care One organization consists of skilled nursing/long term care, assisted living, memory care and rehabilitation facilities on the east coast.

Shnorhokian credits her Hai Tahd work as executive director of the Armenian National Committee-Eastern Region (ANC-ER) from 2006 to 2009 with her ability to think “outside the box” when responding to the crisis. She had been an ICU nurse for 16 years in Chicago before receiving the call from the ANC-ER and she readily made the decision to move to New Jersey, leaving nursing to serve the Armenian cause. “I don’t regret one day, looking back, of what I had done in my life,” recalled Shnorhokian. “Working for the ANC and doing all of that Hai Tahd work, especially during that time, was some of the most amazing things that I carry with me.”

In the course of her work with the task force, there was a request for help at one location particularly affected by the virus, a 200-bed facility with elderly and frail residents, many of whom also have dementia. Although everyone is scared when it comes to dealing with the virus and the potential to bring it home to family, Shnorhokian, in typical fashion, immediately volunteered, was assigned a full patient load and worked a 15-hour shift. “It was one of the hardest days of my life,” she recalled. “I felt like I was never catching up with the needs of the patients. Some of them were really sick, showing signs of COVID.” She mentioned that the phone might have been ringing, but she didn’t even remember hearing it, leading to the concerns of family members during this time, particularly given the restrictions on visitations. “Our priority and goal right now is to take care of your loved ones,” stressed Shnorhokian. “Please be patient. The reality is that the staff are being put into extraordinary situations.”

Shnorhokian has been frustrated, however, that they didn’t know sooner about the threat of the coronavirus because things could have been handled differently if they had known in February what they found out in March. Although there seems to be enough PPE at their facilities right now, she is concerned about running short soon. She commended Care One on its response so far. “We’re not second-guessing expenses. We’re doing whatever we can to make staff and patients safe and protected given the events we’re going through right now.”

None of the Care One skilled nursing facilities can take patients on ventilators at this time because of the building requirements necessary for such care, which led to Shnorhokian stressing the importance of families having serious discussions about code status (the level of medical interventions a patient wants if their heart or breathing stops). “I’m very passionate about advanced care planning, about hospice, about palliative care. I feel that it is an underutilized benefit.” But as survivors of the Genocide, Armenians are culturally averse to discussing end-of-life or hospice. Shnorhokian feels, however, that “the biggest gift we as Armenians can give to our loved ones is not having that guilt for your family members” about not knowing what you would want in such a situation.

Shnorhokian recalled one instance with an elderly COVID-19 patient, during which she and a social worker were able to advocate for the patient, connecting them with the doctor and ultimately transitioning them to “do not resuscitate” and “do not intubate” status, getting hospice involved to keep the patient comfortable. She then mentioned her lengthy conversation with the granddaughter of a 95-year-old patient with dementia suffering from COVID-19. The family member was unwilling to place her loved one in hospice care and keep them comfortable at the nursing home. As of the first week of April, the patient was in the hospital on life support, and Shnorhokian expressed her sincere dismay at the suffering of that patient.

Of course, hospice care has had to change under the current conditions as well. Many long-term care facilities like Care One have hospice patients in residence. In a conversation with Dalita Getzoyan, MA, MT-BC, LPMT, a music therapist with Continuum Care Hospice of Rhode Island, she said, “It seems like almost overnight, I went from being allowed anywhere to having just a couple of facilities I could go to and some people at home who were still comfortable having visitors. And now, I’m not allowed anywhere.”

One facility where Getzoyan regularly saw patients before the pandemic was The Cove at Grace Barker where Lescault said they stopped visitations very early in the crisis, even before RI Gov. Gina Raimondo called for the complete cessation of nursing home visits. Lescault expressed the belief that their policies, similar to other nursing homes, have helped to mitigate the spread of the virus. As of April 9, there were no known COVID-19 cases at The Cove. While Lescault said it’s very unfortunate that music therapists are not allowed to visit at this time, she did say that at the end of life, compassion dictates that one visitor at a time is allowed, including a religious leader (for the sacrament of the sick), while following all the protocols with PPE.

Ani Kiledjian, MA, also works as a music therapist for Continuum Care in RI. From the beginning of visitation restrictions, Kiledjian has been able to maintain some level of contact with her patients at facilities that allow the hospice nurses to visit. “I have had moments where either the hospice aide or hospice nurse will go into a facility in full gear, gown, masks, gloves, and have their time with the patient and then have some time with me. That’s been really beneficial,” said Kiledjian.

Kiledjian and Getzoyan are now offering music therapy to their patients and family members remotely through video conferencing and various social media applications. Through the use of their appropriately-encrypted work phones or tablets, they are able to maintain proper HIPAA confidentiality. For Getzoyan, it’s only recently that she’s had success arranging remote visits with her patients. With relief in her voice, she said, “The sessions were short, maybe 20 or 30 minutes, but they went really well, and I could see the patients responding to the therapy.”

Getzoyan and Kiledjian say they’re both heartbroken that they are unable to support patients who are at the end of life and have benefited from music therapy. Coping with those losses has been challenging for them and involves the understanding that, unfortunately, it’s not something they can control, despite their “heart of healthcare,” as Getzoyan stated. Reflecting on a patient without any family, Kiledjian said, “We are his family.”

When asked what recommendations she would have for people who have loved ones in hospice care, Getzoyan told the Weekly, “The most important thing is not to be afraid to reach out when there is difficulty. Use your resources. As the hospice staff, we still want to be there for family members. We can also help with the grieving process which is significantly heightened at this time. Know that you are not alone.”

Kiledjian and Getzoyan credited their Armenian upbringing with the empathy, commitment and compassion they bring to their work as music therapists in hospice. Both mentioned the strength and resilience necessary for survival, particularly related to the transgenerational trauma transmitted through those who survived the Genocide. “I have patients who have been through similar trauma and grief, some of whom, for instance, are World War II veterans,” said Kiledjian. “My exposure to my rich culture and history has enabled me to connect with these patients with ease and understanding, to help them as well as their families develop tools to cope with their trauma.”

“Being Armenian and having been an advocate for human rights for as long as I can remember have significantly impacted my work as a music therapist in hospice,” said Getzoyan. “Growing up learning about the Armenian Genocide, the trauma that occurred and the impact it has had on multiple generations has helped me develop an innate empathy for others’ grief and suffering. We understand the complicated emotions that can come with loss, including all the stages of grief. We have also learned how to work through these feelings and come out on the other side of it thriving.”

As providers on the front lines of the COVID-19 crisis, all those who spoke with the Weekly expressed concern for their family members and the possibility of transmitting the virus unknowingly to them. This concern not only related to the close Armenian family relationships they share, but also with the Easter holiday coinciding with the crisis and requiring social distancing.

Shnorhokian specifically addressed her decontamination protocols. Her husband Vahig owns a small family dry cleaning business, and they have three children: Aren (8), Aleen (5) and Armen (2). Before returning home from her long shifts, she removes her scrubs and shoes in the parking lot and puts on clean clothes and flip flops, sprays disinfectant on everything, then drives home and removes her clothes again before going straight to a scalding hot shower. All her clothing goes directly into the wash. This is the new normal, and her children know that they need to wait until after her shower to go near “Mommy.” Despite all these measures, Shnorhokian worries about somehow bringing the virus home and also exposing her in-laws, Arturo and Sossie Arlia, who have been caring for the children.

Shnorhokian expressed her gratitude to her entire family for helping her to maintain her sanity during these unprecedented times, including parents Vivian and Krikor Birazian, sister Nayiri Karapetian who is a nurse on the front lines in a hospital, and sister Sona who is a teacher. Her love for family and her Armenian upbringing is evident in all she does. Shnorhokian outlined the sense of obligation that comes with working for the Armenian cause and the ability to work tirelessly for a common goal. “Here it is very similar; our healthcare professionals are working tirelessly leading a courageous fight helping to save those we are caring for knowing the ultimate goal is to combat this disease. Though these times are uncertain, I’ve never felt more confident in my ability to lead and manage this crisis, and I thank my Armenian identity for all of this,” said Shnorhokian.

“The first thing that comes to my mind is the ARS (Armenian Relief Society)…because my grandmother (Baidzar Garabedian) and my mother (Suzanne) were active members. My whole life I saw this call to service, whether it was to the Armenian community through the ARS or through the church. It was very natural for me to get into healthcare,” explained Melissa Simonian, former ARS Eastern Region board member and recording secretary of the Providence “Ani” Chapter. Simonian works for PACE Rhode Island as the Rehabilitation and Nutrition Services Manager; she’s also on the clinical management team.

PACE is a non-profit provider of wraparound health services for frail elders who meet the medical criteria for nursing homes, but they or their family members want them to be able to remain in their homes. Participation is voluntary, and services are funded through Medicare and Medicaid. PACE is national, but each state has its own organization. In RI, there are 350 elders utilizing its services. Participants, about 99 percent of whom are both Medicare and Medicaid qualified, receive complete services, including medical, nursing, rehabilitation, adult day care, specialist care, medications and durable medical equipment through the organization’s home care, day centers and health centers.

Since the COVID-19 crisis, of the three centers in RI, only the largest in Providence remains open to minimize contact and help mitigate transmission of the virus. The state of RI actually asked PACE to keep the Providence day center open in order to potentially accept those who, while not formal participants of the program, might need to be at the center for safety purposes, but their usual center is closed due to the crisis. PACE is able to provide medically complex care, whether in the day center or in the home, for people who may be quadriplegic or suffering from severe dementia or are more self-sufficient.

As part of the response to COVID-19, Simonian explained that the majority of care is now being provided in the home and is limited to essential services as determined by their interdisciplinary team. Prior to the virus, the day center would have about 100 participants, but now it can only accommodate 15 to 20 due to social distancing restrictions. Outfitted with PPE, staff from the day centers are now providing services in participants’ homes. Simonian stressed that many family members are essential workers which has led PACE to provide more home care services of daily living for participants, along with respite in the case of dementia. The PACE plan during the crisis “has been very thoughtful. An incredible amount of work went into this in order to get us here, a lot of hours for us to feel comfortable with really doing a 180 for caring for our folks. We’re settled in now,” said Simonian.

As in the nursing homes, participants with PACE have become accustomed to their routines. Simonian explained that about 75 percent have a behavioral health diagnosis, and the risk of depression is clear, caused by the necessary changes in routine due to COVID-19. “Our social workers have been pounding the pavement” in response, said Simonian, making sure to connect with participants and family members in the home or by phone. “It’s been a very delicate balance between keeping them medically stable and psychologically stable.” She stressed the constant need for phone calls to maintain some semblance of touch, to participants, family members, as well as staff who need additional support during the crisis.

As of April 10, Simonian said that so far only one of their participants tested positive for COVID, spending a couple of weeks in the hospital and being discharged into their care. PACE is now providing that participant’s care, following all the Department of Health guidelines with PPE.

Looking into the future of elder care post-COVID-19, Simonian discussed the familial type relationships they have with their participants, saying that for many of them the PACE staff are some of the only people they see since they have no family. “They buy us Christmas presents. They hug us when they come into the day center,” she said, while sharing her concerns about probable necessary changes after the crisis, since touch has been a way to show care for the participants.

As a descendant of Genocide survivors, Simonian offers some comforting advice. “I think people need to find what’s going to help them get through. It could be faith. It could be a favorite hobby. Unless you care for yourself, you’re not going to be able to care for anyone else. For me, it’s faith. I grew up in a very faithful family and it works for me.”

As a note, just before publication, the Weekly received word from Karine Shnorhokian that she and her husband Vahig tested positive for COVID-19. While Karine’s symptoms currently remain relatively minor, Vahig has a fever and cough. So far, their three children are symptom-free. The Weekly extends its best wishes to the Shnorhokians for a speedy and complete recovery.