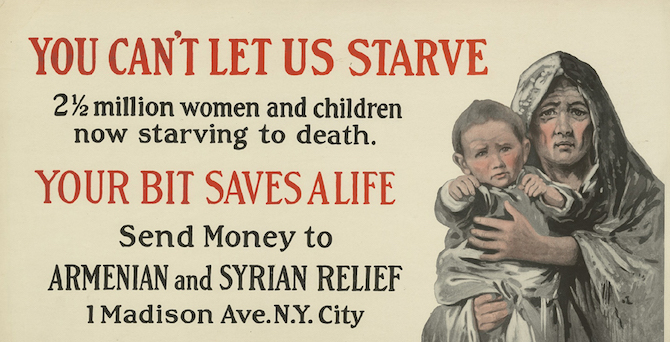

ԵՌԱԳՈՅՆ. Transit advertisement published by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, 28 x 53.5 cm.

From the Princeton Poster Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Negationism effectively prolongs a genocide, which ends only once it is acknowledged by its authors, judged by international instances and punished; according to this model, and considering that the present-day Turkish government denies that there was genocide – as had its predecessors – it is possible to say that the Armenian genocide never ended, that it has been ongoing since 1915

By Lelag Vosguian

As we enter the month of April, as the snow melts into Spring, as the days are stretched longer and shine brighter, Armenians around the world prepare for the commemoration of the Armenian Genocide. They will take the opportunity to grieve their loss, pay their respects to their ancestors and assert their survival and resilience, as they have done for the past decades.

Read also

I believe that we live in strange and wondrous times, that our lives today participate in a fantastic moment of transition in the history of the world. It is hard to believe how fast, how drastically technology has evolved over the past two decades, in the past year, alone. Today, information technologies allow us to have access to any event in any part of the world in real-time. We receive live updates, earthquakes, wildfires, floods, suicide bomber, car crash, virus, death tolls – death tolls rising – and we go on about our business, we are afraid, it never stops.

The question which interests me, the one which animated my post-graduate studies is How can one talk about the Armenian genocide today? Or, more problematically, Should one (still) talk about the Armenian genocide today? Considering the very real tragedies that are part of our everyday lives, considering how many disasters will occur today, in our world, considering the infinite number of contradictory, complementary and competing memories which coexist within the inheritors of different crises, wars and genocides, within one world, country, city, home – considering that there are genocidal policies in place in different countries around the world right now, is it ethical to claim space and attention to talk about an event which occured over a century ago, in a faraway land? Considering that I am writing these very words on unceded land, do I have a right to petition your time and energy to tell you about my victims, my ancestors who are long dead and gone, instead of taking this opportunity, now that I do have your attention, to raise awareness on current, ongoing crimes against humanity?

This is the part where I quote Adolf Hitler who, on August 22nd 1939, in Obersalzberg, right before the invasion of Poland, promised total impunity to his officers by posing Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenian people? In fact, the quasi-totality of books and articles I have read about the Armenian genocide give, at one point or another, a version of this quote. The message is clear: there is a causal effect between the lack of response in 1918, and Hitler’s ability to carry out his genocidal policies; and it is imperative to realize that the Armenian genocide did set a weighty and substantial precedent, which participated in the creation of a world where, henceforth, the Holocaust could happen. This conjecture implies that the Holocaust might have been prevented had the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide been subjected to a thorough trial, followed by judgment, retribution and memorialization; it concludes that recognition and reparation are essential not only for the Armenian and Turkish people, but also for the world at large, for History to come.

We are in 2020, we have a unique perspective on the past century, and it is time to complicate this conjecture. While it is true that the methods used by the Young Turks served as a model for the Nazi regime, while it is necessary to establish a link between the two cases, the conclusion we tend to draw from Adolf Hitler’s “Armenian quote” is no longer persuasive on its own. From our vantage point, we know that despite the prototypal process which followed the Shoah – official judgment by a competent and efficient international instance, condemnation on the world stage, media coverage of trials and more or less global mobilization – other genocidal cases have been witnessed over the past fifty years. How do we account for Cambodia, Rwanda, Darfur, considering that we do speak of the annihilation of the Jewish people? Did we not believe that we lived in a changed world where genocide would be allowed to occur never again?

And so, maybe the knot is situated elsewhere; maybe the problem is not in the way a genocide is “handled” by the international community, in the way it is “dealt with”; maybe the problem is in the concept itself, in the word genocide, that terrible, unknowable thing.

The word was created by the combination of the ancient Greek genos – race, tribe – and the Latin suffix cide – act of killing, and was used for the first time in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin, a lawyer of Polish-Jewish descent, in his volume Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, first treaty adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948, entered into force in 1951, recognizes that, “whether committed in time of peace of in time of war”, genocide is a crime under international law. It further defines the concept in its Article II as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Gregory Stanton, from the genocide prevention organization Genocide Watch, has elaborated a model which apprehends genocide as a (sometimes non-linear) process which consists of ten (permeable) stages: classification, symbolization, discrimination, dehumanization, organization, polarization, preparation, persecution, extermination, and denial. According to this model, denial of intent or actions is not something which occurs after a genocide, but is instead part of its mechanism – it is integrally part of the genocidal apparatus. Therefore, and according to this model, negationism effectively prolongs a genocide, which ends only once it is acknowledged by its authors, judged by international instances and punished; according to this model, and considering that the present-day Turkish government denies that there was genocide – as had its predecessors – it is possible to say that the Armenian genocide never ended, that it has been ongoing since 1915.

***

I always have the urge, at this point, to briefly revisit the history of the Armenian genocide, to talk about what happened, when and where and in what order; I have the urge to inform, cite sources, defend my story. I cannot assume that my interlocutor is familiar with this narrative, nor can I be assured that my reader sympathizes with my position. In this moment, it is my duty to convince you that the Armenian genocide happened. Why is it, that one hundred and five years later, this chapter of a people’s history remains shrouded in suspicion, doubt and controversy? Why is it that we cannot talk about the event without questioning it? One of the reasons may be that genocide, in itself, is unbelievable, unjustifiable and unimaginable. Gas chambers are not believable; women and children walking in deserts; pregnant bellies slashed, horseshoes nailed to bare feet, naked girls crucified. No matter what we know, despites the photographs and testimonies, we cannot understand comprehend imagine explain fathom grasp the reality of genocide; even if we do believe, we believe the unbelievable.

And so proving that a genocide occurred, is almost impossible. How can one prove the “intent” of erasing an entire group of people – not only physically, but erasing their past and future, their life as well as their death and its memory, erasing all traces of their existence, and then erasing the erasure itself? How can one individual, one witness, one survivor present the totality of a state-sanctioned operation which involved virtually every level of government, as well as the civilian population, and which further was mindful of covering its tracks? Most of the time, the convoys were kept in the dark, the existence of the deportees hung in uncertainty and their interpretation of events was informed by rumours and lies. They did not know, could not comprehend the scope of what was happening. Those who survived underwent physical, sexual, psychological trauma which necessarily affected their memory of the period in question. Often, it seems, they did not wish to speak, to testify and share their experience. The survivors were busy surviving, and they could not-would not relive-rehear their story by telling it to their children, by contaminating their descendants with the evil of times past and overcome. And while the survivors tried to forget this experience, the pain, the shame, the humiliation, bury it in a desert silence, the genociders were asserting their innocence, burying their crimes in this same desert. Paradoxically, both were robbing their respective descendants of the truth of their origins; the silence of one and the resounding denial of the other left the next generation with little information and less proof.

In a way, me not knowing my family’s history is the only proof I have, proof that an entity actively set to erasing it. How meagre the inheritance, how poor this knowledge of where I come from and how miserable my chances of persuading you who doubts. How inadequate I feel to convey the truth of genocide, and to convince you of its effects that long endure after the signing of treaties. How ashamed I feel when, assuming the posture of the denialist, I ask for proof.

But of course, proof does exist, and archives have been searched. The happenings of 1915 were common knowledge in the world even as they were unfolding, and historians have since proved beyond reasonable doubt that they predicate the use of the term “genocide”. And yet.

Today, despite the recognitions, memorials, commemorations, most genocides remain non-events or “anti-events”. While the Holocaust was able to integrate our collective consciousness as a historic fact, some argue that most every other genocidal case in History remains fiction – suspect, doubtful, up to debate. How can we strip the word of the denial that is inherently part of its definition? How does a genocide evolve into a fact? Considering that the etymology of the word event relates to something to come, an outcome or a result, could one argue that these historic moments are becoming, and that they will be allowed to be, to come, only once they are accepted, recognized, memorialized by their authors? That the perpetrator is the only one who holds the power to end genocide, while the international community acts as a (symbolic) witness to the avowal of the culprit’s guilt?

What are the effects of this systemic negationism on the descendants of victims and perpetrators of crimes against humanity? How can Armenians evolve in the world when they remain victim-survivors, when their pain is not validated, when their human, territorial, cultural, economical losses are not legitimized? How can Turks interact with the world when they remain executioner-negationists, and can Turkey ever hope to be recognized and respected as a democratic society by the international community so long as it hasn’t faced the specter of its past? Can there ever be hope for cooperation between Armenia and Turkey so long as the latter refuses to affirm that yes, it was genocide? And can there ever be hope for reconciliation and lasting peace when History remains falsified? How can one grieve their Loss when it is negated by the very same one who caused it? One hundred and five years of genocide, stagnating in its ultimate stage, will end only when the denial ends.

***

Descendants of victims of ongoing crimes against humanity are born with a singular heritage: the responsibility to keep alive a memory which will forever remain inaccessible to them. But the descendants of the genociders are also born with a difficult heritage: in order to respect their ancestors and prove their loyalty to their legacy, they must deny that said genocide took place. Of course, Turkey was born from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire – and it is not easy to come to terms with the fact that one’s country was built upon what is possibly the worst crime in international law. It is not easy to betray one’s parents grandparents great-grandparents by accusing them of having committed the most vile crimes, accusing them of deceit, theft, rape and murder.

But the denial is as genocidal as the killing. It is as criminal. And, today, it is an obstacle for justice and harmony between two neighboring nation-states which did not even exist in 1915. It is not easy to forsake one’s history and culture and to admit on the world stage that In 1915, the Ottoman government led by the Committee of Union and Progress carried out a genocide against the Armenian people living in the Ottoman Empire. It is not easy, yet it can be done. It must be done.

A number of philosophers, cultural theorists, literary theorists, psychoanalysts, sociologists, historians and artists have informed my writings. The works of Marc Nichanian, Hélène Piralian, Emmanuel Alloa and Stefan Kristensen have been key to this piece.

Lelag Vosguian holds a master’s degree in Comparative Literature (2018). Her thesis, entitled Le témoignage en littérature d’un héritage traumatique; le cas du génocide des arméniens, is published and accessible on Papyrus, the Université de Montréal’s online institutional repository for theses.