In early April 1917, the United States, besides declaring war on Germany, also ruptured its diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire. Immediately after this decision, German officials, along with Ottoman soldiers, surrounded the campus of the Syrian Protestant College (SPC) in Beirut. SPC closed its doors, and the Germans eagerly awaited a chance and Ottoman permission to occupy the campus. Eventually, the US did not declare war on the Ottoman Empire, and the campus was spared an occupation. But, at this period of uncertainty, SPC professors rushed to the library to burn and destroy all the Armenian books available. These books included the works of famous 19th century Armenian novelists, poets, historians and satirists such as Khachadour Apovian, Raffi, Rafael Badganian, Avedis Aharonian, Hovhannes Toumanian and many others. Perhaps this was the moment when these professors realized that at some point in Ottoman history, the mere possession of an Armenian book, regardless of its content, might be used as a pretext for intervention, occupation and even imprisonment. Thus, they had to burn them all.

Between 1885 and 1918, more than 230 Armenian students graduated from SPC. Most of these students studied medicine, pharmacy and nursing, and some of them read and discussed the books that were eventually burned. This article examines the story of the Armenian medical students at the SPC and highlights their exceptional and difficult roles played during the First World War.

By the end of the 19th century, receiving medical education at the SPC became a possibility for a large number of rich and poor Anatolian Armenians. Various internal and external factors were behind this influx of students from Anatolia to Beirut. Some of these factors included: official language change from Arabic to English in the SPC medical department in 1883; closure of the medical department of Central Turkey College in Aintab in 1888; improvement in transportation methods between Beirut and Adana; importance of medical status and the opening of missionary hospitals in Anatolia.

On July 11, 1883, the Board of Managers of the SPC voted to change the language of instruction in the medical department from Arabic to English, starting after the commencement of the academic year 1883-84. Daniel Bliss, the founding father of SPC, described this event as the most important step taken regarding the intellectual development of the College. According to Henry Jessup, an American Presbyterian missionary, the main reasons for this change were to keep up with the progress of science and allow non-Arab students such as Armenians, Greeks and Iranians who were discouraged by the Arabic language from entering the College and to give students the chance to learn English. Therefore, when English became the language of instruction, the door was opened to all students attending different American missionary schools, from various ethnicities, to come to Beirut and study medicine. Furthermore, with the establishment of the nursing school in 1905, Armenian women from Marash, Adana and Aintab attended SPC to improve their socio-economic status. Thus, before the outbreak of WWI, most of the Armenian students who came to the College had a bachelor’s degree, which they had received from an American missionary school in Anatolia.

Read also

On an intellectual level, students saw medical education as a means to achieve a prosperous professional career and a way to expand their horizons. The professionalization of medicine changed the perception of physicians not only among themselves but also in the eyes of the ordinary people. University certification and the usage of new medical tools such as the stethoscope raised the social standing of the physician and ensured public respect. Perhaps this might explain why there was an interest among Armenians to study medicine, not only in the Ottoman capital but also in Beirut, Paris, Pisa, Geneva and Saint Petersburg.

A few years before the advent of the First World War, Armenian students at the SPC experienced four significant events which had a tremendous impact on their life on-campus. These included the Young Turk revolution and the opening of the Ottoman Parliament, the establishment of the Armenian Student Union, the Adana Massacres of 1909 and the Italian-Turkish War of 1912.

The 1908 Young Revolution put an end to the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II and, for a short period, created a euphoric atmosphere within the empire. Howard Bliss, president of SPC (1902-1920), described the revolution as “Lips unloosed after 30 years of censorship.” To celebrate the restoration of the Ottoman Constitution, students at the SPC participated in public gatherings and demonstrations. Just like in Istanbul, also in Beirut and other cities, people saluted each other as “brothers.” On July 31, 1908, at the Hamidian Garden in Beirut, Armenians participated in the parade and kissed the rifles of Ottoman soldiers as a sign of loyalty. And on the next day, they organized a large demonstration in front of the Surp Nishan church, where Muslim dignitaries also participated and spoke about the importance of “liberty, fraternity and equality.”

Additionally, on the opening day of the Ottoman parliament, the whole student body marched to the Grand Serail in Beirut, where scores of citizens were assembled. With this promulgation, student societies at the SPC flourished, and the College started showing a tolerant attitude towards extracurricular activities, socio-economic and ideological discussions and writings. This permissive attitude allowed Armenian students to form a student union despite earlier faculty hesitancy and reservations owing to officiate wariness of Armenian political activity.

The Armenian Student Union, besides encouraging Armenian students to appreciate their history and language, also collaborated with other student unions to introduce reforms into the Ottoman Empire. Even though the College prohibited the discussion of partisan issues dealing with the political structure of the Ottoman Empire, nonetheless, the students managed to criticize the empire and the socio-political situation.

Dealing with topics on nationalism, patriotism, modernity and progress did not necessarily mean that the students wanted the breakup of the Ottoman Empire and the creation of nation-states. On the contrary, these students criticized the empire for improving it, and they were confident, particularly after the Young Turk revolution, that change was on its way. They emphasized Ottomanism as a means to create an egalitarian multinational state that recognizes the distinctions of its peoples. For Levon Levonian, instructor of Ottoman-Turkish at SPC, the removal of the Sultan’s autocratic rule, which suppressed and controlled political life, helped the people to realize that they are “Ottoman citizens” and should not rely on outsiders in language, education, commerce and technology. Levonian was confident that during this new era, different ethnic and national groups would establish closer relationships with each other, and the knowledge of the Ottoman language will be more widespread.

The euphoric dreams of Armenians were shattered in mid-April 1909 when the Adana massacres started. Reports from the province estimated that the massacres culminated in the death of perhaps 25,000 Armenians.

The massacres played a pivotal role in agitating Armenian students at the College. After all, most of these students had relatives living in the vilayet and had little information about them. On April 27, 1909, Vartan Topalian, Haigazun Varvarian, Boghos Seradarian, Nishan Baron Vartan and Karekin Vartabedian of the senior medical class, petitioned the faculty to be allowed to proceed to the vilayet of Adana to volunteer their services to aid victims of the massacres. The faculty voted “that these gentlemen be thanked for their loyal offer of help to those in distress and anxiety,” but permission was not granted. A few days later, another student, Benné Torossian, left the College against the advice of the president and without permission to take part in the relief work at Adana. As a consequence, the faculty asked the president to reprimand Mr. Torossian for his breach of discipline.

The only relief came to the Armenian students when they were informed that the College was preparing a medical commission to go to Adana. In response to the call of the American Red Cross committee at Beirut, a medical commission reached Adana on May 5, 1909. Dr. Harry Dorman, professor at the SPC, was in charge of the commission, which consisted of two students of the fourth-year medical class, Dr. Kamil Hilal, Dr. Fendi Zughaiyar and Miss MacDonald together with two German missionary sisters from the Johanniter Hospital of Beirut. The commission carried with them a complete set of surgical instruments, including sterilized dressings and sutures, as well as condensed milk, tinned soups and drugs. A few days later, Benné Torossian and Dr. Haigazun Dabanian joined the delegation. Dr. Dorman described the participation of Torossian and Dabanian as “deserving of special credit in coming to Adana at this time, for they knew that in so doing they ran the risk of government suspicion and arrest.”

If the Adana massacres affected the students psychologically and mentally, then the Italo-Turkish war of 1912 affected them physically. On February 24, 1912, two Italian military vessels bombarded the Beirut harbor and sank an Ottoman torpedo boat. The Ottomans were heavily beaten, and their naval presence at the Beirut harbor was annihilated. SPC students, faculty and even residents of Beirut were packed in safe locations, and the “American flag was placed upon the lightning-rod of the College tower.” Howard Bliss described the war as being unnecessarily barbarous. At that time, Bliss was unaware that the Italo-Turkish war was just the beginning, as an apocalyptic war was on its way.

On October 19, 1915, the Ottoman authorities in Beirut requested from the SPC faculty a list of the names of all the Armenian students enrolled at the College, and a “similar list including the names, occupations, and whereabouts of those Armenians, who were formerly enrolled as students but had graduated or had left the College.” Ironically, the Chief of Police added that the request was made “in order to protect the students and not for the purpose of molesting them in any way.” Requesting the names of students and organizing statistics was an essential task given by Talaat Pasha, the Minister of Interior, to all the provinces, including Beirut, in order to keep track of the deported and non-deported Armenians. Fortunately for some Armenian students, Howard Bliss and the faculty took a protective decision and refused to hand in the names of the former students and the nurses, and only accepted to submit the names of enrolled students who were under their “protection.” Bliss probably knew well that by handing the names and addresses of the alumni he would jeopardize their lives, particularly at a time of deportations. After all, Bliss was the one who extended sympathy to all the Armenian students, “who knew, or, worse, did not know, of the tragic fate of their dear ones.” While faculty discussions about the names were taking place, the deportation caravans were already on their way toward the Syrian desert.

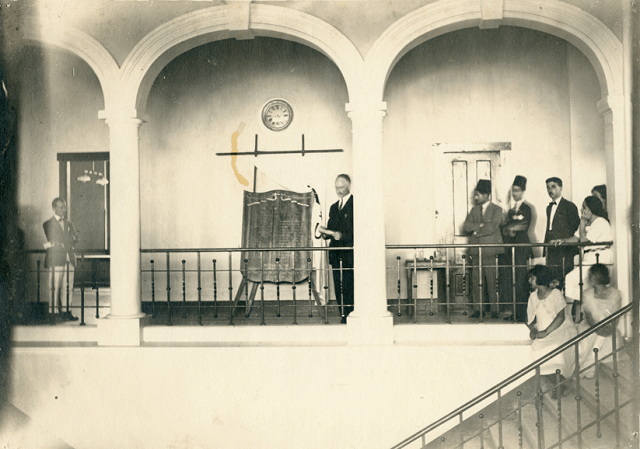

SPC doctors, nurses, and medical students preparing themselves for the Suez Canal expedition. (Source: AUB Archives)

The SPC faculty had the leeway of rejecting some of the Ottoman demands, such as giving the information of Armenian medical alumni, mainly because of the medical services SPC doctors provided to the Ottoman army. With the outbreak of the war, the American Red Cross committee in Syria offered medical help to Jemal Pasha, Minister of Marine and Commander in Chief of the Fourth Ottoman Army. The pasha accepted the offer and “requested that an American field hospital be installed in the desert south of Beersheba to care for the wounded in the attack on the Suez Canal.” Dr. E. St. John Ward, Professor of Surgery at SPC, was chosen as director of the expedition, and Rev. George C. Doolittle of the American Mission, was appointed as associate director. The agreement with Jemal Pasha was that the relief expedition “should serve as a tent-hospital of 200 beds at Hafir el-Auja, a station on the Egyptian frontier, one day’s ride from Beersheba.” On January 17, 1915 in a special train provided by the Ottoman government, the members of the expedition left Beirut and headed safely to Hafir-el-Auja. Besides the director and the associate director, four sisters of the Kaiserswerth Mission, three graduate doctors and 16 senior medical students from the SPC, including six Armenian students, took part in the relief mission. The expedition carried with it a large number of fully equipped tents and a three months’ stock of medicines. The difficulties faced in conducting such a desert hospital were enormous. The water supply was inadequate. Transportation was entirely done by using camels, and sandstorms were frequent. However, the hospital impressed Jemal Pasha and took care of 220 Ottoman soldiers. After six weeks, the last of the wounded reached Jerusalem. With him, the members of the expedition returned to Beirut and organized themselves to show the pasha readiness for similar future work.

When the hostilities at Gallipoli began, Dr. Ward, who had just returned from the Suez expedition, did not wait much to travel to Istanbul with his team to assist the wounded and organize a 500-bed hospital with the American Red Cross. The medical missions sent by the SPC in January 1915 to the Suez Canal, and from May to September to Istanbul, together with the dental services of Dr. Dray to the Fourth Army, created a favorable situation with the Ottoman authorities and prepared the College to survive the war. Jemal Pasha not only kept the College open throughout the war but also furnished it with wheat and food supplies at the most challenging times. Not only the pasha benefited from the services of the trustworthy SPC medical alumni, but the College also had the advantage of bargaining with the pasha on various matters from food and protection to academic curriculum and student activities.

The medical profession during the war became so important that it gave Armenian doctors and nurses the power to survive the Genocide, cure diseases, and most importantly, bribe Ottoman officials to save a family member, a well-known Armenian intellectual or even thousands of deportees. However, it is not my intention to generalize that all these professionals had such an experience; more than 200 Armenian doctors, nurses and pharmacists either were killed during the Genocide or succumbed to the diseases they sought to treat. Nonetheless, many of those who survived were capable of doing so because, in certain situations and at different spaces, they became more valuable than the vast majority of the population. Thus, survival depended on the peculiar relationship between the medical and the national identity of the doctor in question.

The conditions of the war and the deportations of Ottoman civilians created the ideal situations for the proliferation of diseases and the spread of epidemics. Historians argue that more Ottoman soldiers perished from the deadly effects of microbes and bacteria than from bullets and bombs. Malaria and typhus did not differentiate between civilians and soldiers.

Unburied corpses placed on the roads or thrown into the rivers (Tigris and Euphrates), became breeding grounds for disease and contaminated the water. Local villagers blamed the deportees for the crisis and complained to the Ottoman authorities. The authorities, who were worried about their troops, found in these epidemics an excuse to initiate new massacres in the desert camps.

Ideologically, Armenian doctors did not just face microbes on the battlefield or in hospitals but also became part of a community labeled as microbes. Young Turk leaders, who described themselves as “social physicians,” such as Drs. Nazim, Behaeddin Şakir, and Mehmet Reşit politicized medicine and medicalized the “Armenian Question.” Vahakn Dadrian argues that Young Turk doctors and medical personnel abused the medical profession as a tool of Genocide and planned medical murder. For the Young Turk leadership, the war provided an opportunity to solve the “Armenian Question” once and for all by implementing radical medical measures on the Armenian population. For example, Mehmet Reşit, Governor of Diyarbakir province 1915-1918, described Armenians as “a load of harmful microbes that had afflicted the body of the [Ottoman] fatherland.” Reşit fused the language of science and medicine with nationalist rhetoric and firmly believed that as a doctor, it was his duty to eradicate microbes (i.e., the Armenians), from the body (i.e., the Ottoman Empire).

After the end of the war, Bliss asked the SPC alumni to share with the College their war experience. A large number of Armenian students complied with the request and wrote back to the president about their dreadful experience. Most of them were traumatized by the Genocide and its impact on their families. For example, Hovsep Tatarian mentions that he was forced to join and serve in the Ottoman army for 16 months. He was sent to the Egyptian front where he lost his medical diploma, and presumably, Dr. Vahan Kalbian, who was in the Suez relief expedition, found it and sent it to the SPC. In August 1916, the British imprisoned Tatarian, but he was released and allowed to serve in the British army as a medical officer. After serving in the British military for a year, Tatarian traveled to London to continue his medical studies. Still, on his way back to Egypt, his boat was torpedoed, and fortunately, he was saved by the Japanese who took him to France. Similarly, Meguerditch Baghdassarian was taken as prisoner by the British in the Hejaz and interned at Heliopolis. There he was released on parole and put in charge of medical work at the POW camp.

On the other hand, some students expressed disgust and used Orientalist language to depict the empire as backward, chaotic, and barbarian. For example, Sarkis Semerjian indicates that only after the war did he feel powerful enough to describe his hatred of the Ottoman Empire. Additionally, Semerjian used cholera as a metaphor to suggest that the Young Turks were more dangerous than the illness itself.

Hatred towards the Young Turks and the Ottoman regime was not just expressed by Armenian doctors who suffered during the war, but also by Syrian doctors like Amin Abu Fadel and others. Abu Fadel, while serving in Rayak, insisted on helping the Armenian refugees to control the Typhus epidemic, but according to him, none of the officials cared until it became uncontrollable. Like Armenag Markarian, who mentioned the death of his Armenian classmates, Abu Fadel also mentions in his letter the death of his Syrian classmates: Suleiman Salibi, Abdallah Sawaya, and Ali Alam el din.

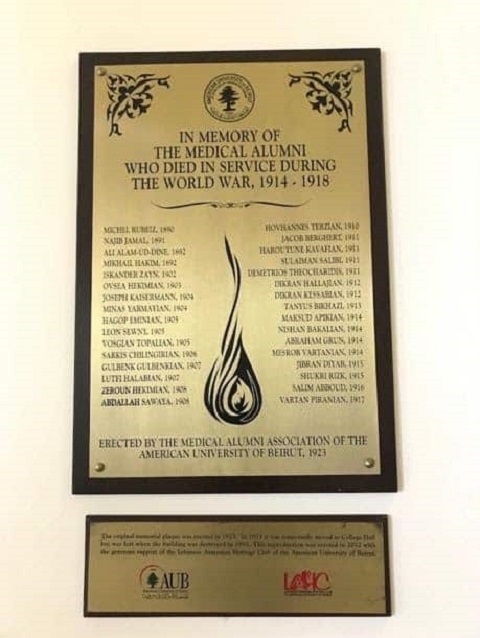

If Tatarian, Semerdjian and Abu Fadel were fortunate enough to survive the war and share their story, other doctors were not. Around 28 Armenian doctors and pharmacists died during the war—some such as Drs. Dikran Hallajian, Haroutyun Kavafian and Minas Yarmayan were deliberately murdered in the courtyard of the hospitals in which they served, while others, such as Drs. Benné Torossian and Armenag Markarian were hanged in public squares presumably for their political activities.

The First World War dramatically affected the lives of Armenian students and alumni affiliated with the SPC. Like other Ottoman citizens, the alumni served in the army, while the students had to bear the moral and psychological impacts of WWI in general and the Armenian Genocide in particular. Armenian physicians used the medical profession as a survival mechanism to overcome the difficulties of the Genocide and the war. They served in the Ottoman army at a time when their entire community was being labeled as “traitors.” Politically, the SPC preferred to sacrifice some of its archival collections and Armenian books, and even to expel its Armenian instructors to please Ottoman authorities or to prevent trouble. But at the same time, the safety of the students and the alumni was much more important than any military order. Bliss and his colleagues vehemently refused to give the list of Armenian students and alumni to protect them. In the end, the war altered not only student lives but also the very essence of identities. The multiethnic empire was destroyed, nation-states were created, and national divisions became apparent.

In the early evening of June 26, 1923, a large congregation of doctors and pharmacists gathered in the upper foyer of West Hall, at the American University of Beirut, to witness the unveiling of a tablet inscribed with the names of thirty-two medical alumni who perished in the course of World War I. Seventeen of these medical professionals were Anatolian Armenians who had come to Beirut in the early 1880s to study medicine at the SPC. During the Lebanese civil strife, in 1976, the bronze memorial was moved to the university’s College Hall to protect it from damage and the possibility of theft – but it lay there for years, and eventually was lost. On November 1, 2012, a new tablet was constructed and permanently installed in its original location in commemoration of AUB medical doctors, pharmacists, and nurses who saved the College from closure during the war and sacrificed their lives for the well-being of others.

Hratch Kestenian

Main caption: Armenian nurses (Rosa Kulunjian and Ossana Maksoudian) of the 1908 nursing class with their colleague (Adele Kassab) and professor (Ms. Jane Van Zandt).