The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. PARIS, FRANCE – While the footprint of Armenians in France can be traced back to the Middle Ages, it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that they made an indelible mark on the country, particularly in Paris’s arrondisements [administrative districts] that served as a point of refuge for Armenian Genocide survivors and gave them the chance to recreate their lives in their adopted country. In the 1920s, an estimated 50,000 Armenians lived in France, ranging from laborers to intellectuals to artists, who became active members of society and paralleled their livelihood with ardent efforts to preserve their profound culture. The community ingrained itself in the social, political and economic fabric of the country that exists to this day.

When the pandemic began circulating throughout Western Europe earlier this year, France took strict measures, including closing travel borders, shutting down nonessential businesses and restricting travel to within 60 miles of a citizen’s home. Although the restez chez vous [stay at home] orders, which have been in place since March 15, have been challenging for the people and the economy, which have not faced a crisis of this magnitude since World War II, infections have slowed. The current estimate in the country stands at 145,000 confirmed cases and 30,000 deaths among the population of 67 million. To ease the economic and social implications, preexisting government-funded programs, like food vouchers, have increased and a plan is in place to ease lockdowns starting in mid-May.

Amid the backdrop of the Tour Eiffel, the stamp of the Armenian community in Paris is evident throughout its neighborhoods, from the commanding Armenian Cathedral off the Champs-Élysées, to the solemn genocide memorial of Gomidas Vartabed in Jardin d’Erevan by the Seine, to the ever-present institutions that open its doors to not only Armenians but to the masses. The estimated 100,000 Armenians who live in Paris perpetuate their heritage with pride and protect their history with vigor, flourishing particularly in the artistic, academic, journalistic and cultural sectors, despite the deadlock caused by the pandemic.

Editor-in-Chief of the Nouvelles d’Arménie and Co-President of the Coordination Council of Armenian Organizations of France, Ara Toranian has been a vigorous figure of the French-Armenian scene and reflects the gumption of Armenians who continue to carry out their work in a society that has been shut down.

Read also

“As everywhere in the world, the pandemic has impacted community life,” said Toranian. “All activities have been stopped, masses were celebrated behind closed doors, and many media, especially print, have had to stop production.”

On his end, Toranian was able to publish the April and May issues of Armenian News (Nouvelles d’Arménie) and is currently laying out the June issue with his editorial staff. He acknowledges that the paper’s financial situation is “very difficult since the advertising budget has collapsed.” A burglary in their office premises last October contributed to the uncertain future of the newspaper, which continues to report, despite the dismal updates.

“The pandemic has resulted in the death of many association leaders and it’s been a real slaughter,” said Toranian, who notes that the community section has been replaced by obituaries. “We regret the death of Patrick Devedjian, president of the departmental council of Hauts-de-Seine, and a former minister and lawyer who was very involved in the defense of the Armenian cause.”

Just two months prior to his death, Devedjian was in attendance at the CCAF’s annual dinner in January, sitting between France’s President Emmanuel Macron and Turkish historian Taner Akçam.

“Partrick Devedjian was in great shape that night,” said Toranian, who highlighted that the CCAF awarded him with a medal of courage in 2016, which took place in the presence of then-President François Hollande. “He seemed happy and proud to see the progress made by the Armenian community in France, which is the only one, along with the Jewish community, to be able to organize this type of event.”

Thanks to the staunch efforts of committed individuals like Devedjian, the Armenian Genocide is officially recognized by France and the nation continuously advocates for awareness and justice. But for the first time since the 1970s, the April 24 commemorations were cancelled because of the pandemic, a contrast to last year, when several thousand people attended the commemoration, during which Prime Minister Edouard Philippe “made a speech of exceptional strength.”

“Although the commemoration came at the hardest time of confinement, we still got it done,” said Toranian, who noted that their organization respected the limit of no more than six people present at a gathering.

The ceremony took place on April 24 in front of the poignant Gomidas memorial statue, dedicated to the 1.5 million martyrs who perished in the Armenian Genocide. Those in attendance included Nicole Belloubet, Minister of Justice, who represented the French government, Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris, Hasmik Tolmadjian, Ambassador of Armenia to France, Mourad Papazian, co-president of the CCAF and Toranian.

“The protocol manager for the Orsay wharf, Hélène Stein, read a short text paying tribute to the victims and we observed a moment of silence before concluding the ceremony,” said Toranian, who, along with CCAF focused on bolstering virtual commemorations with the campaign slogan, “I stay at home, but I don’t forget.” They also included genocide-related publications in the press, including the daily Le Figaro, the leading newspaper of France.

Creatives Aram and Virginia Serovpyan have forged artistic lives in Paris since the late 1970s, making the enriching past accessible to current and future generations. They both serve on the board of the Péniche Anako, a cultural mainstay on a canal barge on La Villette Basin, that once symbolized Armenian Genocide survivors and now serves as a center of music and multi-cultural performances on a boat formerly owned by the Armenian Red Cross. Since its founding 10 years ago, Virginia and her husband have organized concerts, from jazz to folk to bluegrass, along with lectures, screenings and dramatic readings, among many other imaginative endeavors. The open-door policy enhances the cultural exchange and dialogue.

“It’s an amazing project that exists with a shoestring budget and where many artists, young and old, have met, some of whom have continued together to form their own groups,” said Virginia, who serves as director of programming of Péniche Anako, which has been dubbed “Paris’s alternative cultural scene.”

She said people of all nations come together, especially from places that are “community centered,” like South Americans, Middle Easterners and Africans, linking all kinds of artistry and ideas.

The music and programming, however, has been interrupted.

“There has been a loss of cultural life during the pandemic,” said Virginia. “We are encouraged to do things online, but it doesn’t take the place of human interaction.”

Professionally trained musicians, the Serovpyans are entrenched in the Armenian cultural life and generously share their knowledge through workshops, performances and presentations, and tours in and out of France – but now find themselves communicating and teaching virtually.

They teach modal music digitally to their students, three fourths of whom are not Armenian, and they continue to collaborate with the Paris-based Polish theater group Teatr Zar, which asked the couple to create recorded audio listening lessons.

“It’s demanding to prepare but it’s very interesting for us too because there is learning on both ends as we figure out virtual techniques like sound engineering,” said Virginia, a soloist and concert artist originally from Washington D.C. “It’s definitely a challenge and you can say it’s satisfying in a different way since we can continue our work.”

Aram and Virginia founded the folk and troubadour music ensemble, Kotchnak, close to 40 years ago, as well as the Centre for Armenian Modal Chant Studies – Akn, originated in 1998, which specializes in liturgical chant and where Aram serves as Director of Armenian Liturgical Chant. Virginia is a soloist of both professional ensembles that attract French and Armenian audiences. They have also shifted their ensemble’s activities to the online platform.

“It certainly does not replace face to face teaching,” said Virginia. “When we are physically together, we live and feel the music, and that’s something that can’t be replaced by the internet.”

But “the show must go on” according to Aram Serovpyan, who is originally from Istanbul and holds a PhD in musicology. A source of frustration has been the postponement of a CD recording project with Akn that was originally slated for the last week of April.

“We had people coming from different countries, like Poland and Belgium, to complete this project and everything was arranged until the lockdown went into effect,” said Aram, who served as the Master Singer of the Armenian Cathedral in Paris for 30 years, noting the importance of being “alert and inventive every second.”

During their time indoors, Aram posts videos on their YouTube channel, including excerpts from Lenten and Easter chants. They are also working on musical programs and preparing songs from the region of Akn to be featured by Houshamadyan, a non-profit founded in Berlin, Germany that reconstructs and preserves the memory of Armenian life in the Ottoman Empire through research.

“It has been fruitful and we appreciate the time we have,” said Aram. His wife notes they have “projects galore” and find inventive ways to keep themselves productive. Their three children, Shushan, Vahan and Maral, have also embarked on creative paths.

The Serovpyans observe that the situation in Paris is slowly improving, though the abundant cultural life of the city is still on pause.

“The coronavirus has pretty much put a stop to the gatherings so only people who have the means and ideas to do things online have continued to share their music,” said Virginia. “We’re continuing with our projects as much as we can but we are in an artistic community where most of our work has to do with gatherings, so we are all at a standstill.”

The pandemic hit just as Collectif Medz Bazar, an urban Diaspora band, was entering an extensive world touring schedule, inspired by the release of their third album, “O” (see this Mirror-Spectator review). Influenced by their own musical traditions, the group invigorates traditional classics while collectively composing arrangements of folk music and original compositions. Within their layered songs they share inflections of bountiful genres and sounds, from Middle Eastern percussion to Iranian folk music to hip hop, with a strong message of upholding equality and addressing social and political issues.

While their plans to perform their cross-cultural and unique blend of music in countries such as Portugal, Germany, Switzerland, Turkey, Georgia, France and the US have been put on hold, the ethnically mixed eight member band – Raffi Derderyan, Shushan Kerovpyan, Vahan Kerovpyan, Elâ Nuroğlu, Marius Pibarot, Ezgi Sevgi Can, and Sevana Tchakerian – are not sitting idly by, even as their bandmates are living in different countries.

“However difficult it is for everybody, we try to live the present situation in a constructive and uplifting way, using the overwhelming time at home to write, create, practice, observe the world around us and take care of ourselves,” said the Portugal-based Vahan Serovpyan, who is a co-founder of Collectif Medz Bazar and plays the percussion and piano.

“Seeing our musician friends and inspiring artists responding to the pandemic in such creative ways gave us ideas to keep on creating and producing music for our audience,” said singer and accordionist Tchakerian, a co-founder of the band, who currently lives in Armenia.

Before the pandemic struck, the band enjoyed a full week of rehearsals in Paris in mid-February, leaving the musicians with a lot of material to work on independently. Their first confinement video, filmed from each band member’s home, was the Kurdish song Min Digo Melê.

Collectif Medz Bazar, which formed in 2012, is open to livestreaming a concert in the near future if they can find a way to synchronize their microphones live – but they miss the synergy of a live concert.

“During these last few weeks musicians coped, sometimes through silence, sometimes

through home recordings and live concerts, but at the end of the day, the emotions shared by

an audience experiencing a concert can’t be delivered digitally or replaced with technological tools,” said Tchakerian, who acknowledged unease about the unpredictable future of the culture and the arts during this time of crisis.

The band members, however, lean on one another and find inspiration as they evolve personally and professionally.

“We immediately found a connection among one another,” said Serovpyan. The band at first played covers and folk music from Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish, Greek, and North American traditions, but “started finding our own sound, which consolidated as we began writing originals.”

The tightknit group draws from its strong foundation of friendship and respect as they weather current challenges and collaborate to create new musical works while sharing it with their audience.

“The music world, like all others, is somehow adapting to the situation,” said Serovpyan. “But even when isolated, we tend to gather, in a different way, through social media, posting music and videos, and other means of exchange, and above all, we take the time to question what seemed obvious or unquestionable.”

Looking towards the future landscape of music and the world at large, Tchakerian is aware life will be different and the pandemic may spur change.

“Most of us will be much more socially conscious, change our way of consumption, and we won’t take little things for granted anymore,” said Tchakerian. “I think this has been a humbling experience for us humans, because it touches all of us, regardless of our socioeconomic situation.”

For Serovpyan, he vacillates between the impression that things will change and that not much will be affected in the long run. What is clear, however, is that the pandemic has shown cracks in society that have been ignored.

“Even the established discourses and ways of life have been exposed to the public in all their fragility, giving an opportunity to question the systems we live in and the authority of those in power,” said Serovpyan. “Many people have opened their eyes and witnessed things that were conveniently denied. There is a lot to think about, a lot to change by our own will.”

Collectif Medz Bazar has come far since their first gatherings almost a decade ago where they simply had the desire to “jam and share music we loved with each other.”

“As we grew, the band gained different meanings for each of the members,” said Tchakerian. “When performing in Turkey, I personally feel it as an act of activism and that we contribute to the reviving, even slightly, of our indigenous cultures, languages, songs in our ancestral lands.”

Living in Armenia for the past five years, Tchakerian has witnessed transformation in the homeland, the power of the youth and the encouragement of free thinking, uniting those who strive for “tolerance, openness and love.”

“I hope that the arts will find their essential role in motivating people, defending freedom and expressing love and fraternity,” said Serovpyan. “We in Medz Bazar are certainly determined to pursue this mission.”

Right before the pandemic became headline-making news, Armenian youth were enjoying each other’s company in a cocktail bar in Paris’ city center, organized by the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) Young Professionals Paris Chapter, where a hundred young Armenian professionals came together for social and networking purposes. As of now, the chapter’s programming has been cancelled through the summer, including their popular annual outdoor event, according to Robin Koulaksezian, a member of the YP Paris Committee.

The leadership and members remain connected mostly through their Whatsapp group and partake in virtual events with fellow chapters.

“We are participating in the YP Live events, organized by different YP chapters each week, which have been very popular during the lockdown,” said Koulaksezian. They are also coordinating with AGBU France to bring attention to AGBU’s humanitarian relief aid related to COVID-19.

The Paris YP Chapter focuses on two main activities – conferences with entrepreneurs, such as Armenians who have founded their own start-ups, or young Armenians in the fashion industry in Paris; and Afterworks, which encourages French-Armenians to come together and support one another’s professional ambitions and cultural traditions.

“Afterworks are organized every two months and we plan various activities such as Armenian cooking workshops, wine tasting and yoga classes among others,” said Koulaksezian, who recently published a travel guide book, Little Armenias, about the Armenian Diaspora in the French and English languages. “Our group is composed of French-Armenians of all backgrounds including some who grew up with AGBU’s activities, others who are second and third generation, as well as those who came from Armenia to study and work in Paris.”

Jirair Jolakian, Director and Editor of Nor Haratch Weekly, which is published three times a week in Armenian and once a week in French, describes the Paris Armenian community as fruitful and productive, particularly in regards to the cultural life.

“Though the population is spread out and there is no centralized body, it is a colorful and active community,” said Jolakian. “The April 24 commemorations unite Armenians as well as the annual telethon and fundraisers that benefit the homeland.”

The activities that contribute to the richness of the community, however, have come to a halt since the pandemic penetrated the country and particularly the capital city, where Nor Haratch is published.

“The pandemic brought with it new challenges, including a disruption in postal services that didn’t allow the print copies to reach the homes of subscribers,” said Jolakian, who increasingly turned his attention to the newspaper’s website where the news was updated daily, with a special focus on COVID-19 and how it has affected France, Armenia, Artsakh and the world at large. Articles closely followed the uptick in cases, new scientific discoveries and government responses. The site, which is in both French and Armenian, also reports on the political news of Armenia and those related to Armenians.

“Our digital site and our newsletter filled in the role of the print paper so we could still deliver the news every day,” said Jolakian. “We were able to keep our audience informed digitally of the ongoings in our community, Armenia and Europe.”

Nor Haratch comes on the heels of the historic independent daily Haratch, founded in 1925 by Schavarsh Missakian, that served as the longest-running French-Armenian publication until it ceased operations in 2009. In order to uphold the journalistic tradition of the French-Armenian community, Jolakian, alongside other noted intellectuals, reignited the newspaper. As it ushers in a new chapter of growth and readership, Nor Haratch provides much-needed dissemination of the news during these turbulent times.

“The pandemic caused significant changes in our community but we tried to find local solutions,” said Jolakian. “News shifted more towards digital, classes were taught virtually and workshops were done online, showing us that from now on we should all be more prepared for what’s to come.”

Jolakian’s service to the community expands beyond the world of journalism. Before his commitment to Nor Haratch, he formed deep roots in the Armenian theater scene in Paris over the last three decades, and with a close collaboration with metteur en scène Arby Ovanessian, he helped stage close to 150 plays independently, without the support of an established organization.

He looks towards the future generations to continue their involvement in the Armenian cultural life in Paris and perhaps place more of an onus on sharpening the Armenian language skills.

“Paris, and France in general, have had challenges in preparing the upcoming generations to speak the language,” said Jolakian, who directed an educational theatre workshop in Armenian at MGNIG organization. “In the past, the Armenians from the West brought in new forces to strengthen the teaching of the language, but now it’s been replaced with Eastern Armenian and there is no language unification.”

One place for the youth to be exposed to the Armenian cultural life is Péniche Anako, which Jolakian, one of the founders, describes as a vibrant gathering place, allowing participants to “engage in Armenian cultural events, enjoy Armenian food and mingle with people of all backgrounds in one of the most important centers for world music.”

Dr. Dickran Kouymjian, who established the Armenian Studies Program at California State University, Fresno, currently resides in Paris, a city he has spent a considerable amount of time in during his productive career, which includes teaching at the Sorbonne. He continues to partake in the academic and day-to-day life in Paris, which he says “has been impacted by the pandemic in the same way as it has around the world.”

“Nearly all programs have been cancelled, including the annual April 24 march that leads to the Turkish Embassy, and was instead replaced by a virtual program,” said Dr. Kouymjian, Emeritus Professor of The Berberian Chair of Armenian Studies. “Most gatherings, Armenian or not, have been forbidden by the French government. As in the US, there is a thawing out of confinement, but it is fortunately not as chaotic.”

He notes that the presence of the Armenian community is “quite large” and permeates into the academic fields, including the Chair of Armenian Studies at Inalco: Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales and at the Institut Catholique, both in Paris, where there are “vast Armenian holdings in its library.”

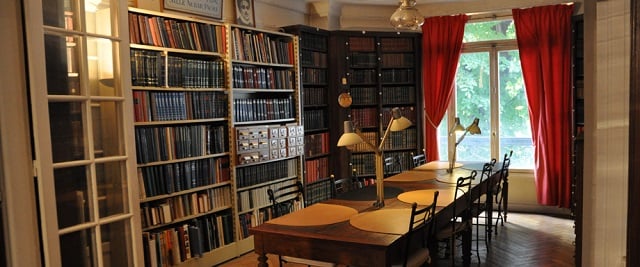

Dr. Kouymjian also cites the Bibliothèque Noubar (AGBU Nubar Library) as a significant resource that is “very rich” and open daily to the general public.

Founded in 1928, the Nubar Library, named after its founder, Boghos Nubar Pasha, was a “major cultural center for the post-genocide Armenian diaspora,” according to director and historian Dr. Boris Adjemian, who asserts that the library has long been among the “pillars of Armenian cultural life in Paris” and the only one that exists today.

“In the last decades, the role of the Nubar Library has changed a lot,” said Dr. Adjemian. “It strengthened its role in scholarship, developed partnerships and co-sponsored activities with many universities, research centers and other Armenian, French or foreign institutions, and its audience became more international, affecting the Armenian diaspora and beyond.”

The doors to the major research center, with over 43,000 books in its library, have been sealed for over two months.

“Since the lockdown was implemented, travels in and out of Paris were drastically limited, and all the cultural institutions were closed,” said Dr. Adjemian. “However the activity of the Nubar Library does not only depend on its visitors, since it acts like a research center on the genocide, diaspora and other related topics so this activity was not interrupted.”

Some of these projects included teaching a class on the history of the Armenian Genocide to international students at the American University of Paris, which was taught online, and several research projects such as the publishing of a book on the history of Armenian immigration to France, that will be released later this year. The Nubar Library continues its editorial activity and has published, on a regular basis since 2013, the bilingual (French and English) multidisciplinary journal Études arméniennes contemporaines, which is accessible online.

As weeks of the lockdown stretch into months, people at home are turning to more lighthearted outlets that also help entertainers muster through the cancellation of live performances. Pop rock musician Mika Apamian utilized his YouTube Channel to share “Le Grand Confinement” parody videos and songs with his audience – maintaining his creative spirit while offering a moment of escape for his listeners. The covers, which range from Lady Gaga’s Shallow to Queen’s Don’t Stop Me Now along with French singers Johnny Hallyday, Patrick Bruel and Charles Aznavour, offer levity during the unlikely times of the pandemic, which forced his tour with French singer Clarika to be cut short.

“The first day of the quarantine in Paris, I was singing Charles Aznavour’s song Hier Encore and it became clear to me that there will be a big difference between yesterday, today and tomorrow,” said Apamian, a self-proclaimed fan of Aznavour who he has imitated for years. “So I had the idea of rewriting the lyrics and making my first video.”

In just a couple of days, the video reached 5,000 views and he decided to continue the “Le Grand Confinement” series after receiving favorable feedback. Apamian harnesses a positive view of the situation, looking at the lockdown as time to create.

“People thanked me for giving them happiness and joy during these difficult times,” said Apamian. “They also congratulated me for my voice and my energy in the videos.”

Apamian, who composes his own music and plays guitar, cello and duduk, released his debut album “L’Année Du Taureau” while performing as a regular at the historical landmark Maxim’s de Paris. The comedian-singer keeps himself busy through the production of his parody videos, practicing instruments for hours on end, and teaming up with other artists virtually – he recently played the duduk in an online collaboration with Clarika.

“This particular period allows me to think about my role in society,” said Apamian. “I know that I don’t want to live like I did and that I want to build something new. I hope a lot of people found the time to think about themselves and what they really want for our world.”

Main caption: Mika Apamian