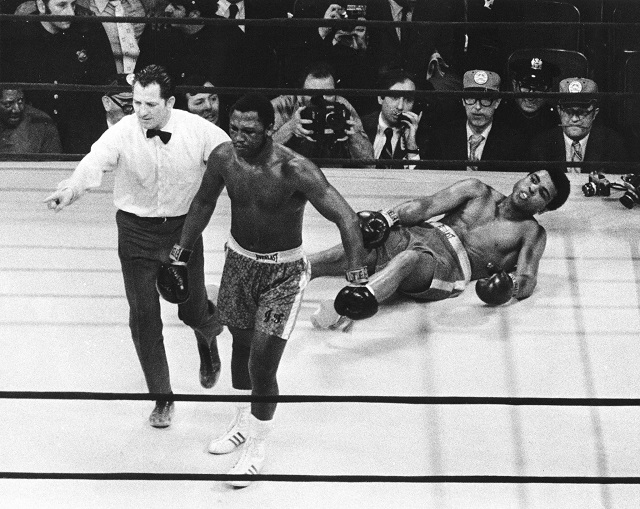

The Armenian Weekly. In 1971, I was 12 years old, and Muhammad Ali was all the rage in Tehran. All were in awe of the brash young American boxer who was a sight to behold in and outside the ring. But the mood in my insular working-class Armenian neighborhood was ecstatic when Ali lost to Joe Frazier in the historic fight that year. My friends and I cheered for Frazier. That’s because the Christian Frazier had beaten the Muslim Ali. All we knew was that a few years back Cassius Clay had converted to Islam and had taken the very Islamic name, Muhammad Ali. That was enough for the Armenians to judge the quality of Ali’s character. In our small world, that was enough to decide who to cheer for in a boxing match. There was nothing more to ponder or consider in my ghettoized community on the outskirts of Tehran, where self-awareness was primarily defined by Christianity, the 1915 Genocide and Armenian nationalism.

In 1974, by forces beyond my control or understanding, I ended up in New York City. I was going to a public high school in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The student body was 95-percent Black and Latino. The school seemed to be straight out of a scene from the 70s sitcom Welcome Back, Kotter, or should I say, the other way around. Most of my teachers were young progressives committed to their craft; they taught me a great deal. About a year later, I read the Autobiography of Malcolm X. It was the first book I managed to read in English. I struggled, but somehow managed to get the gist of it.

In the short time since I had first watched the Ali/Frazier fight, my life had changed; I had experienced and seen so much. Nixon had been impeached and resigned in disgrace. I had watched on TV the ragtag North Vietnamese, by sheer force of will, expel the humiliated world superpower from their homeland. New York City was bankrupt and yet edgy with an alluring vibe. The color and character of the diverse neighborhoods, which have since given way to banal gentrification, was captivating. Boomboxes blared in the graffiti-covered subway cars that creaked and clanked, that were hellishly hot in the dog days of summer and ice cold in the winter. The city was alive, vibrant.

But, back to Ali and Malcolm X. In high school, it did not take me a long time to learn a bit more about US history. In Iran, I had learned about racism and the scourge of slavery in Western countries, but there was no depth of knowledge. In the US, I came to know more about Ali and the kind of man he was. Against all odds and at great personal cost, Ali had defied, resisted and fought a system that had no qualms about forcing Black men to soldier in Vietnam while perpetuating the racist status quo here at home. His resolve and the simplicity of his message spoke volumes about the man and his character. Of course, Malcolm X had a direct role in Ali’s awakening. Malcolm X spoke powerfully and did not mince words in exposing institutional racism and violence in the US. Like so many other Black leaders of conscience, he too paid the ultimate price for having the audacity to demand the right to live with dignity.

Read also

As the years passed, I witnessed first-hand the consequences of deeply rooted systemic physical and economic violence against African Americans. Acts of police brutality, vigilantism and killings are too many to recount. What I will recall that horrified me most was the 1985 police bombing of the MOVE compound in Philadelphia. The compound was in fact a house in the middle of an urban city block. Six MOVE members and five of their children perished in the conflagration. Some 60 houses, almost the entire neighborhood, were burned to the ground. To the establishment in power, these were armed radical Blacks who needed to be dominated and put in their place. But African Americans do not have to be armed and radical to meet death and destruction. In 1921, during two days of racial violence, White vigilantes set to flame some 35 blocks in a prosperous Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The violence killed and injured hundreds of Blacks and rendered thousands of them homeless. American history is replete with such acts of wanton violence and horror against people of color.

This pattern has not ended. In fact, in the past decades, we have seen police forces nationwide become more militarized and aggressive with the sharp points of their bayonets always aimed at the Blacks. The same is true of White supremacists who are armed to the teeth and seem to be itching to unleash terror and mayhem against their perceived enemies.

Today is June 9, 2020. The New York Times front page article is headlined, “George Floyd, Whose Death Energized a Movement, will be Buried Today.” The United States is convulsing, once again, in reaction to the shocking repeated acts of police violence and vigilantism against its Black citizens. I am reminded of an Armenian saying that translates to, “The knife has reached to bone.”

But what does this have to do with me? You may ask what does it have to do with Armenians?

The Armenian national consciousness is marked by the denial of justice for the Genocide, the ultimate crime of violence, committed against our people more than a century ago. We carry that wound and live, every single day, with the generational trauma of that state-sponsored violence. Our national wound will not heal until justice is served. But to deserve justice for one’s own cause, one must support the cause of fellow citizens who struggle for human rights and dignity. If we remain silent and do not actively engage in the movement for social justice, here and now, we will be on the wrong side of history. How could we then expect others to support our just cause?

When I was 12, I should have cheered for Muhammad Ali. But I guess I could be forgiven. It was a long time ago. I did not know any better.

Vahak Khajekian

Caption: Boxer Joe Frazier is directed to the ropes by referee after knocking down Muhammad Ali during the 15th round of the title bout in Madison Square Garden in New York on March 8, 1971. (Flickr/Rogelio A. Galaviz C.)