The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. DETROIT — “That generation…”

Stephan Karougian, the 80-something male soloist of St. John’s Armenian Church Komitas Choir in Detroit, was telling me about his parents, as I sat in his living room, interviewing him about his life in Armenian music. He shook his head and sighed. He didn’t really expound upon those two words, but his tone of voice was enough to tell the story.

Karougian’s father had been born in Pingyan, a village in the Province of Sivas in Ottoman Turkey, very close to the large town of Agn in Harput province (the Ottoman borders divided up the Armenian villages of that region, which also included Armdan and Divrig). He told me that when his father would gather with friends, they would sing a song in Turkish beginning with the words “Egin de veran olmush” (“Agn is in ruins”). It was a very sad song about their region. But when Karougian first told me about this song, he didn’t say that it was a song about the Genocide, he simply told me that they sang it.

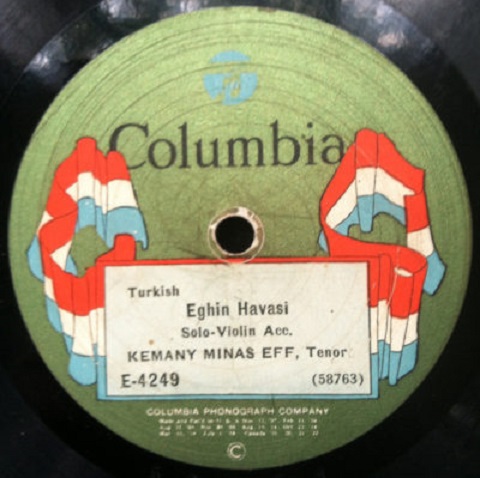

I recognized the words as a variation of the lyrics of Egin Havasi a well-known Anatolian song which has been performed in both Armenian and Turkish. I played for Karougian my copy of the 1917 New York recording of this song by violinist-singer Kemani Minas [kemani is a title in Turkish given to a violin player, as udi is to an oud player]. It was indescribably sad. Karougian listened silently and began again to tell me about his family story, his life story.

Read also

The senior Mr. Karougian had been a volunteer soldier who fought under General Antranig in his campaigns against the Turks in the Caucasus, briefly gaining control of Western Armenia just as the Armenians of those regions were being decimated. They didn’t get as far as Pingyan. After the retreat and the Sovietization of Armenia, Mr. Karougian left for America, sailing first into Istanbul, which at the time was under the post-War Allied occupation. He couldn’t bring himself to go any further. “He didn’t want to leave the land where his fathers were buried,” said Stephan. Let it never be said that the Bolsahyes are not patriotic Armenians.

Karougian settled in Bolis, married and raised a family. He had to be careful though, as he had sustained bullet wounds to the chest in battle. He scrupulously avoided allowing his chest to be exposed in the sight of a Turkish official, as it might be revealed he had served in combat against Turkey. Of course, Karougian was not the only Armenian in Istanbul who had to be careful in his comings and goings. They all did. Mention of what the Armenian people had been through during the First World War was not possible in public. Yet the Armenians found ways in which to remember their past, one of which was through music, and perhaps surprisingly to some, in folk songs sung in Turkish.

Armenians singing folk songs in Turkish was nothing new, as many with roots in Anatolia can attest. Musicologist, folklorist, and student of Gomidas’ music, Mihran Toumajan, refers to the popular Turkish language songs of Anatolia. “These are those songs, which have been utilized equally by all peoples living in Turkey… composed in a simple popular style, easy to understand, probably by ashoughs [minstrels], of which the number of Armenian ashoughs (as is clear from history) has been sufficiently large.” (Hayreni Yerk oo Pan, 1972). 19th century Eastern Armenian writer, folklorist, and children’s author Ghazaros Aghayan also chimed in on this subject: “It is necessary to consider as national-popular [azkayin zhoghovrtagan] those songs and song-mixed tales which although they are not in the Armenian language, but are the compositions of Armenian ashoughs or which are typical of them and are spread among the people…we commit a great error, when we collect and print the Armenian-language ballads of an ashough, but we neglect the Turkish-language songs.” (Daraz, 1893).

Kef Time Music

Not only did the Armenians sing “kef time” songs in the Turkish language, but they also sang of pain of the Armenian Genocide. The once-well-known Der Zor Cheollerinde (In the Deserts of Der Zor) describes the suffering that took place during the death marches, and was created and sung by the women and children during their deportation to the Syrian desert. In the 1920s, more than one Armenian recording artist in America made a phonograph disc of this song.

Yet the Armenians in Bolis, and also elsewhere, had other songs that they would sing, songs whose origin was somewhat mysterious, and ought to be the subject of investigation by folklorists and musicologists. Songs whose meaning was not completely obvious, and which perhaps weren’t originally about the Genocide at all, but which were interpreted by Armenians in 20th century Istanbul, as well as in many parts of the Diaspora, as expressions of their historic pain.

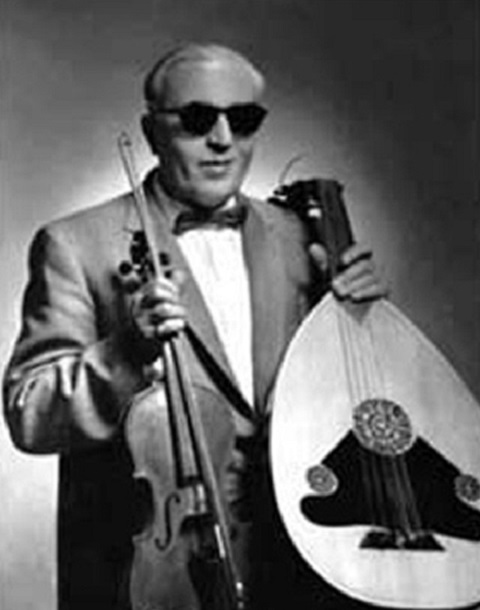

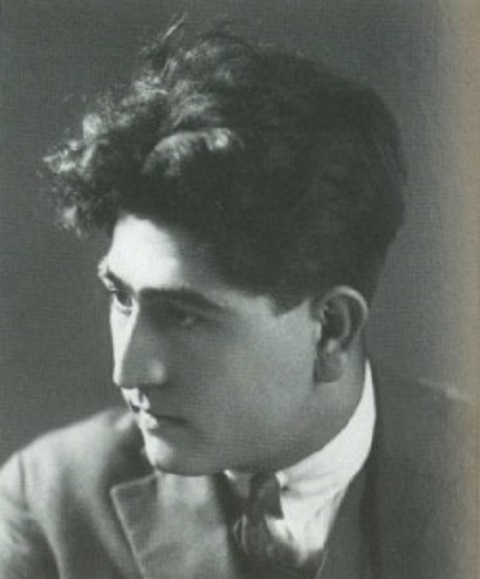

One of those songs seemed to be Egin Havasi, the song Karougian was speaking about. The famed Udi Hrant, for example, had recorded this song in both Turkish and Armenian, and the version recorded in 1917 by the mysterious vaghamerig (one who died young) Kemani Minas, apparently an immigrant from Malatya, was a best-seller in the Armenian-American community for some 15 years. (I would be remiss if I didn’t relay the information given to me by oudist Richard Hagopian that while Minas sang the vocals on that recording, the deeply moving violin was actually played by the master musician Harry Hasekian of Marash, who lived most of his life in Watertown.) But neither Udi Hrant’s, nor Kemani Minas’ recording actually used the words “Agn is in ruins.” Everything about this song was vague.

I had been hearing about other songs like this for some time, though. Deacon Charles Hardy (Kherdian) of Racine, Wisconsin, and currently of the St. James parish in Evanston, Ill., shared with me that his wife, who grew up in Beirut, was the daughter of a survivor from Gesaria (Kayseri, Turkey). Her father used to sing a Turkish song called Gesi Baghlari (Vineyards of Gesi) while working or cleaning his store in Beirut. According to Hardy, the song was really about the Armenian Genocide. I had heard of this song before; it was popular among the Armenians of Gesaria and can be seen referenced in survivor memoirs. I didn’t know it was about the Genocide. On the surface it’s a sad love song with references to the Kayseri region — Gesi is a nearby small village whose vineyards were apparently a sort of vacation spot. It has been recorded by many modern Turkish performers and a glance at the lyrics doesn’t really reveal any direct or indirect references to the Genocide. On the surface it is about the vineyards of Gesi and about lost love. While both Armenians and Turks consider it a sort of regional anthem, some Armenians, at least, in addition to Hardy’s father-in-law, attached an additional meaning to the song. Ethnomusicologist Melissa Bilal, originally of Istanbul, concurs with the opinion that the while the origin of the song may be as yet unclear, Armenians certainly sang it with the intention of expressing their feelings about 1915. She shared with me that she had an aunt who was fond of the song and claimed it was written by an Armenian. Melissa further pointed to the line “there is death, and there is cruelty in this world” as referring to the Armenian experience. Yet it is clear that this song predates the Genocide. I have a recording of it from 1917, that belonged to my great-grandfather Hovhannes Vartoogian, himself a survivor from Fenesse (one of the villages of Gesaria), which was well worn-out and must have been listened to many times. The recording was made at the same session as Kemani Minas’ version of Egin Havasi, by a different singer, a Gesaratsi vocalist named Garabed Merjanian. Merjanian’s lyrics are incredibly hard to make out, but he seems to be singing the following:

The vineyards of Gesi are a field with roses

Mother I am going, and you protect your head

The mother-in-law is faithless and the son-in-law is an infidel (gavur)

Don’t send me, mother, beyond those mountains

May others not burn, my mother burns for my pain

Beyond this mountain, choice mint grows

My tobacco smoldered without my fire being lit [a proverb meaning I didn’t have a chance to enjoy my youth]

A fate happened to me, worse than my death

Don’t send me, mother, beyond those mountains

May others not burn, my mother burns for my pain

While these lyrics are incredibly vague, and could have come from the pre-Genocide version of the song (Turkish sources claim the song was about a young bride in an unhappy arranged marriage who was sent to a village beyond the mountains to her husband’s family), the words Merjanian chose to sing in 1917 were certainly suggestive of war, forcible conscription of the Armenian men from the villages, and other aspects of the Genocide. The line “a fate happened to me worse than my death” alone is certainly suggestive of something more than just an unfortunate arranged marriage. In the end, the story of this song reminds one of two very well known Armenian songs Groong and Dle Yaman, both of which are today often sung in conjunction with Genocide memorials or similar events, but actually long predate the Genocide; Groong dates back to the 17th century. But since Groong is about the sadness of being away from one’s homeland, and Dle Yaman is a sad love song with references to the landscape of the Van region, where Armenians no longer live due to 1915, both have been turned into Genocide anthems. It seems that in an unofficial way, this is also what has happened with Gesi Baghlari in the minds of some Armenians. In fact, the combination of the sad love theme with references to now-lost homeland geography is extremely similar to Dle Yaman.

The song Chanakkale Ichinde (Çanakkale Içinde, or “In the Dardanelles”) has lyrics that are much less vague, yet I kept coming across strange hints about this tune. While on the surface, and according to Turkish sources, it is a Turkish patriotic song about the Battle of Gallipoli, with the narrator a soldier who is marching off to almost certain death in battle, there seems to be more than meets the eye. First of all, it is the only Turkish patriotic song that is continually played by Armenian folk musicians who sing in Turkish. This is bit weird in and of itself — Armenians in America might play a lot of Turkish “kef time” songs, but you don’t see them going around singing the Turkish national anthem. Yet, this song had a degree of popularity in the past, and is still known by many. For one thing, New York oudist Charles “Chick” Ganimian used to play and sing it in his live performances as a wild, heavy kef tune, memorably in a live recording captured on tape in the late 1970s which was later re-released on a CD by Armenian music producer and kanun player Ara Topouzian of Michigan. One might think that Chick simply heard this song on an old Turkish record, didn’t know or care what it was about, liked it, and performed it. Those who accuse American-Armenians of cultural illiteracy probably assumed that this was the case.

However, in a paper written in 2010 by oudist Antranig Kzririan (of Philadelphia, now of Los Angeles), an interesting tidbit was mentioned in his interview with fellow Philadelphia oud player David Hoplamazian:

“There were certain songs that they always sang and played — some were Genocide remembrance songs. These were songs sung in the Turkish language that reminded Armenians of pre-Genocide times. One of Chick Ganimian’s songs was about the killing and death that occurred during the Genocide. I remember how they would argue on stage about whether it would be appropriate to play the song on one particular occasion. This kind of thing was over my head at the time as I was a youngster. I was just happy to meet Chick who was one of the top oud players that my family always talked about.” (Hoplamazian, quoted in Kzirian, The Oud: Armenian Music as a Means of Identity Preservation, Construction and Formation in Armenian American Diaspora Communities of the Eastern United States, 2010)

When I asked Hoplamazian personally what song he was talking about, he couldn’t recall. But based on what I know of Ganimian’s repertoire, the only song he could possibly have been talking about — certainly the only song that has these type of references, which is that popular, and which Ganimian was known for playing on stage, was Chanakkale Ichinde.

The “Turkish nationalist” credentials of the song come into even further question when we realize that the first ever recorded version was made by Greek-American singer Marika Papagika in 1924, just after the armistice between the Allies and Mustafa Kemal at Mudanya. Though the song is typically considered a reference to the Battle of Gallipoli that took place in 1915, the lead-up to the 1923 armistice was similarly called the “Chanak Crisis” and was stand-off between Turkish, Greek, and British troops that took place in the same area. The fact that Marika was a well known Greek nationalist with many patriotic songs to her credit, and that her version has the narrating soldier in the song departing “from Edirne” (instead of Istanbul) where the Greek army was stationed at the time, lends a vague pro-Greek meaning to the song.

The Armenian element to the song becomes much more obvious when we consider the recording made by vocalist Boghos Kirechjian, also known as Udi Boghos, brother-in-law to the well known Udi Hrant. In a special recording session that took place in Istanbul in 1951, Boghos made his recording of this song, along with several Armenian-language songs that were sung by both himself and Hrant, who performed on the oud. The rest of the band was composed of Turkish gypsies. These recordings were made by the US-based ethnic record company, Balkan, which was owned by Ajdin Asllan, an Albanian from New York. They were made for distribution in this country, and not in Turkey. One would assume that releasing Armenian-language songs on disc in Turkey was politically impossible in the early 1950s. Similarly, the public would not accept an Armenian singing a tune that was widely perceived as a Turkish patriotic song. But how did Boghos himself perceive it? We don’t really know, but we do know that Chanakkale was the last major battle where Armenian soldiers serving in the Ottoman Army were armed and allowed to fight in combat alongside their Turkish fellow citizens. After that time, Armenians were sent out of the regular units and formed into labor battalions, where they were used to build roads, and finally dig their own graves, which they were then shot and buried in by their Turkish overseers. In Boghos’ version of the song — and Chick Ganimian’s — we find the line:

“In Chanakkale they shot me / and they put me in the grave before I was dead / Alas, my youth!”

French-Armenian writer Vazken Shoushanian also recalled singing this verse as an orphan survivor in Aintab during the French occupation, when the “deep and centuries-old Oriental city suddenly belonged to us,” and “Like little street heroes we broke through it, chewing and ruminating on some Turkish song, enjoying a sweet freedom, which similarly would come from death:

“In Chanakkale they shot me / and they put me in the grave before I was dead / Alas, my youth!”

Finally, I asked renowned oud player, singer, and expert of Armenian and Turkish music, Richard Hagopian of California, about the Chanakkale song. Hagopian would not confirm that it was about the Genocide, but told me a fascinating story. When Hagopian was young, Soghomon Tehlirian, the man who assassinated Talaat Pasha, retired and moved to Fresno, where he is now buried. A banquet was held in Tehlirian’s honor, at which young Hagopian was present. Some people approached him and said “You know, Baron Soghomon plays the oud a little, and he likes oud music. Why don’t you get up and play something for him.” Hagopian got up and took his oud. “He had a face like an angel,” he now says of Tehlirian. “You would have never thought he had killed a man.” Hagopian, nervous, began to play a bit of a taksim (improvisation) but didn’t know what to play for Tehlirian. “I mean, here is this man, who killed the top Turk.” Since a lot of the music Hagopian played was Turkish, or considered by some to be in a Turkish style, the young musician was nervous and unsure of what piece to perform. Then Tehlirian looked at him and said “Dughas, Chanakkale kides” (My son, do you know “Chanakkale”) “Anshooshd Baron Soghomon, payts dajgeren eh” (Of course Mr. Soghomon, but it’s Turkish). Tehlirian told him, “It doesn’t matter, I told you to play it, so play it.”

Back to Egin Havasi

To return to the beginning of our article, and the song Egin Havasi. Now that we seem to have established the fact that Armenians used Turkish songs with more than one meaning, even if the same songs were sung by the Turks themselves, Egin Havasi seems much more obviously, if not blatantly, a reference to the Genocide ‑ though more specifically, the massacres of 1895-1896.

Avedis Messouments, noted Armenian composer and collector of Armenian ethnographic folk songs, who was born in Arabkir and spent most of his life in France after the war, brought attention to the verses, sung in Turkish, “Agn is in ruins / the nightingale doesn’t sing / My husband is in a far place / my eyes don’t see him.” Messouments continues:

“Therefore, Agn is a ruin … of course, the Armenian didn’t destroy it, but rather the Turk, and it is not the Turk who would weave a song about his destroying. And who is the primary emigrant, if not the Armenian? But the Armenian sang in the Turkish language; first, from fear of being punished for the Armenian language, and then, so that the Turk would also hear it, learn it, and sing it. And that is what happened.”

These were the same lyrics that Stephan Karougian told me about. Another Armenian writer who remembered his elders singing those lines was Nigoghos Sarafian of Paris, who grew up in Bulgaria. Incidentally, the line “Agn is in ruins” is not in Udi Hrant’s published recorded version, though he in the second verse Hrant sings the quite suggestive verses: “Green frogs croak in the ponds / My arms were destroyed, I was left in the desert / Without a mother, without a father, in foreign lands…”

The ethnographer Verjine Svazlian, who wrote a whole book in Armenia about Turkish-language songs of the Genocide survivors (mostly discussing the Der Zor song) quotes these lines but beginning with “May I be a sacrifice to the bygone days” rather than the line about the frogs. The same lines turned up in a performance of the Der Zor song which I found on YouTube, where an individual named Gabriel Assad changes to Egin Havasi halfway through singing Der Zor. Kemani Minas, who recorded the song in New York in 1917, as discussed earlier, didn’t mention any of these things directly. But the fact that he chose to record it in fall 1917 at the same time and place (New York) that Garabed Merjanian recorded Gesi Baghlari, Zabelle Panossian recorded her famous version of Groong and Armenag Shah-Mouradian recorded Gomidas’ masterpiece Andouni, all with similar themes, points to a trend. The fact that he sounds like he’s crying when he sings it, randomly throws the word mayrig (Armenian: mother) into an otherwise Turkish song, and — if I’ve correctly identified him as the violin player Minas Chaghatzbanian of Malatya, who died in Fresno a year later — if we realize that he came to America in 1913 and left his wife Varter behind, and he’s now recording this song in 1917, as the Genocide is ongoing, it all starts to add up.

It is unquestionable that the melody and many of the various lyrics of Egin Havasi existed before the 1895 massacres. In Hovsep Janigian’s Antiquities of Agn, published in 1895, includes the first mention of this song. Janigian, a 19th century folklorist who collected the history, folklore, songs, wedding traditions, and dialect of Agn in his book, claimed that the original song was related to the bantoukhd (migrant worker) movement among Armenians, who would travel to Istanbul or some other far-off urban center to make money for their family who were left behind in the village. The well-known song “Groong” has the same theme. Janigian claimed that what we call Egin Havasi (referred to by him as “Ale Geozlu”, Turkish for “Weeping Eyes”) was written by an Armenian woman in the 1840s or 50s whose husband had gone as a bantoukhd to Egypt. Janigian mentions that the song also has Turkish lyrics, but he didn’t write them down, instead giving several verses of lyrics in Armenian. The lyrics are almost identical to what Udi Hrant sings in his Armenian-language rendition. Most likely, Hrant learned these from his singing teacher, the well known Istanbul “oriental” singer Yeghiazar Garabedian (known to the Turks as Agyazar Efendi), who was born in Agn, and seems to have left as a child due to the devastation of the city in 1896. The folklorist Mihran Toumajan also collected several Armenian-language verses to the song in his Hayreni Yerk oo Pan (volume 2). In a footnote, he tells the reader that he had also heard a Turkish version of the song when he was a child in Sepastia, from a youthful blind minstrel at the Soorp Nshan Monastery. The minstrel’s Turkish language Egin Havasi, Toumajan tells us, was “about the events of 1895.” It turns out that while the city was spared the initial massacres of 1895 by bribing the government (Agn was a wealthy town, whose compatriots living in Istanbul were mostly moneylenders that at one time controlled the Ottoman financial sector), it was later devastated in 1896 in retaliation for the Bank Ottoman incident, whose leader, Papken Suni, was a native of Agn. Evidently, while the song was written by an Armenian, sung in both Armenian and Turkish, and discussed separation and loss, the lyrics specifically referring to the 1895-96 massacres were added later. However, this soon became the most popular version of the song, as evidenced by Messouments, Sarafian, and others who claimed that the first line of the song was “Agn is in ruins.”

As for Stepan Karougian, I finally asked him directly what the song was about. “Egin de veran olmush,” he told me, “Agn kantuvadz eh.” (Agn has been destroyed). I pressed him “what do you mean, destroyed?” “You know, the Genocide…” he responded. Then I asked him, “Didn’t you tell me Udi Hrant used to sing this song in the gazino [Turkish cabaret]” “Of course, how many times did I go and hear him singing there!” “Well,” I asked, “what did the Turks think when he got on stage and started singing about “Egin veran olmush”??”

“I guess, they didn’t know what he was singing about,” replied Karougian. But Richard Hagopian had a different response to this. “They know all of it,” he told me. Searching my record collection as well as YouTube, the only example I could find of a recording where the singer actually says “Egin veran olmush” (Agn is in ruins), was by a Turkish singer, who from what I could tell, was a known nationalist and active politically. There is a lot of talk about cultural appropriation in our day and age, but that takes the cake. Perhaps it is the most correct to say, as with the Genocide in general: they know, but they won’t admit it.

By Harry A. Kezelian III

Special to the Mirror-Spectator