The Armenian Weekly. In this week’s empowerment series, we learn about three Armenian women who dedicated their lives to science in the 1900s. Paris Pishmish, Alenoush Terian and Anna Kazanjian Longobardo were scientists at a time when being a woman in the field did not come easily.

Nonetheless, they blazed trails and took on leadership roles in a field where few women existed. In their careers, at a time in which few women filled these roles, they not only held the titles as firsts, but their work impacted the work of future generations.

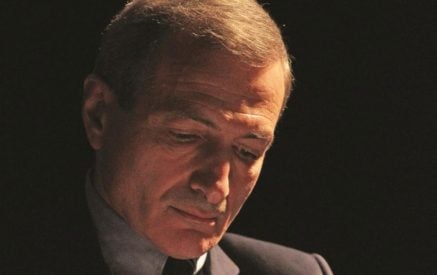

Paris Pishmish de Recillas

As a Mexican Armenian woman, Paris Pishmish, known as one of the preeminent female astronomers not only worked hard in her own career, but she also carved out time to mentor other women who wanted to become astronomers as well.

Pishmish, born Mari Soukiassian in Constantinople on January 30, 1911, was the daughter of Soukias Soukiassian, the great-grandson of Mikayel Amira Pishmish who was a member of a powerful class of Armenian commercial and professional elites titled amiras. Filomen, her mother, was Mateos Izmirlian’s niece who was the Patriarch of Constantinople from 1894 to 1908 and Catholicos of All Armenians until 1910.

Pishmish attended an Armenian elementary school and later became the first woman to graduate from Istanbul University with a degree in mathematics and classical astronomy in 1933. She then graduated from Harvard University with her Doctor of Science in mathematics in 1937; in 1939, she became an associate researcher at Harvard College Observatory. An expert herself, she drew great inspiration from the likes of astronomers such as Harlow Shapley, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, Bart Bok, Donald Menzel and Fred Whipple, to name a few.

During her time at Harvard College Observatory, she met a Mexican mathematics student named Felix Recillas, started tutoring him in German, and ended up marrying him in 1941. Their two children, Elsa, an astrophysicist and Sevin, a mathematician, helped transform the field of astronomy in Mexico. Pishmish stayed in Mexico and taught at the National Autonomous University connected to the Tacubaya Observatory as an astronomer for over 50 years. Women in the early 1900s were not encouraged to pursue careers in the sciences despite their talents or desires. At the start of her career, Pishmish worked as a translator as well as a support scientist at Erwin Finley-Freundlich before she went on to work on her own projects.

Her work was unique as she focused more on the kinematics of the galaxy, as well as the photometry of nebulae and the determination of radial velocities. She developed the first-ever photometric investigation of stellar clusters – revealing three globular clusters as well 20 open stellar clusters and worked on figuring out the effects of interstellar absorption on stellar distribution while relying on various stellar populations to explain the origin of the spiral structure of the galaxy.

Translation – she was incredibly smart!

She shared her work with the world, publishing more than 135 scientific articles in well-known journals including the Astronomical Journal, Astrophysical Journal, Astronomy and Astrophysics; she also presented at conferences, including one at the Byurakan Observatory in Armenia at the invitation of Viktor Hambardzumyan.

Her accomplishments were beyond extraordinary. She introduced the field of applied astronomy to her students in Mexico, and many of her students later became very well-known astronomers—Arcadio Poveda, Eugenio Mendoza, Enrique Chavira, Debora Dultzin, Alfonso Serrano, Alejandro Ruelas, Marco Moreno.

She was awarded a Science Teaching Prize by UNAM for her diligent work as a teacher and mentor as she advised her students and coworkers, setting a prominent example of devotion to science.

As a strong, passionate woman in the astronomical field, Pishmish was involved in a variety of organizations such as American Astronomical Society, Royal Astronomical Society of Great Britain, Academy of Sciences of Mexico, Mexican Physical Society and International Astronomical Union (IAU) where she was a member of several commissions.

Pishmish penned a memoir titled Reminiscences in the Life of Paris Pişmiş: A Woman Astronomer along with her grandson Gabriel Cruz González, where she described her visits to Armenia and her love of the language and culture. Fluent in Armenian, Turkish, French, English, German, Italian and Spanish, Pishmish was able to share her research and learn from her colleagues around the world.

She died on August 1, 1999, but her work and legacy live on through her students and her contributions to the field of astronomy.

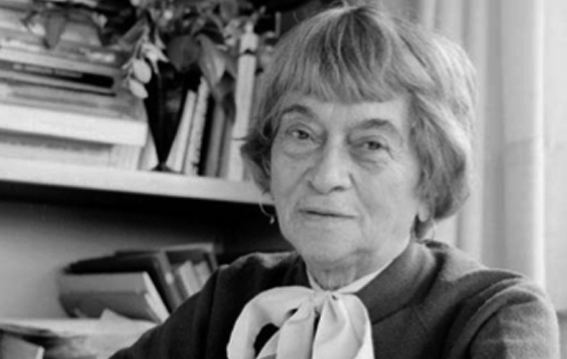

Alenoush Terian

Alenoush Terian, regarded as the ‘Mother of Modern Iranian Astronomy,’ was an astronomer and physicist, born and raised in an Armenian family in Tehran, Iran. The first Iranian woman to become a physics teacher, Terian was the founder of the first solar telescopic observatory in Iran.

Born to a French mother and Armenian father in 1921, she was fluent in French, Persian and Armenian, and understood Turkish and English.

After graduating from the University of Tehran in 1947, she worked in physics laboratories and quickly became head of operations. She aspired to continue her studies in France and worked tirelessly to convince her professor, Mahmoud Hesabi, to help her get a scholarship. He, however, refused to help her simply because she was a woman.

But Terian stood firm. She didn’t let his unwillingness to help discourage her from pursuing her dreams. She persevered and went to Paris with the help of her father and studied at the Faculty of Atmospheric Physics of the Sorbonne, eventually earning her master’s degree in 1956. She was offered a teaching job there but respectfully declined because she wanted to go back to Iran. Confident in her trajectory, she became an assistant professor of Thermodynamics in the Department of Physics at Tehran University.

She was the first female professor of physics in Iran in 1964. Two years later, she became a member of the Geophysics Committee of Tehran University and in 1969 was selected as the chairwoman of the study group of solar physics at the Geophysics Institute at the university. She then went on to work at the solar observatory which she founded and eventually retired in 1979.

She never married or had any children of her own, but she dedicated her entire life to her students and the classroom. One of her students stated, “She always said she had a daughter called moon and a son called sun.” In her will, she left her home to the Armenian community of Nor Jugha and to students who did not have a suitable place to live.

On her 90th birthday, the Iranian Parliament honored her during a ceremony. She passed away in 2011 leaving behind an indelible mark on history, astronomy, physics and the Iranian-Armenian community.

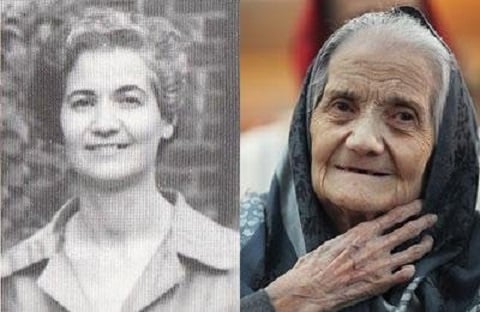

Anna Kazanjian Longobardo

Finally, we meet Anna Kazanjian Longobardo – the first woman to receive a B.S. in mechanical engineering from Columbia University. One of the founders of the Society of Women Engineers, she was elected as a fellow and became the first woman to receive the Egleston Medal for her engineering achievements. She was later listed as one of New York’s “100 Women of Influence.”

Although she was born in New York City in 1928, she was born into a family of Armenian immigrants. Her father was an Armenian immigrant from Aleppo, Syria, and her mother was an immigrant from Constantinople, Turkey. Anna’s mother’s maiden name was Yazejian; her family survived the Armenian Genocide during WWI and was able to move to the United States. Additionally, her uncle Haig Khojassarian, also referred to as Hojassarian, was a well-known educator and leader.

Kazanjian exhibited a passion for science at an early age. She was devoted to her work but also spent ample time motivating other women. “We, the women, should work on our self-esteem and not allow failures,” she said. “I try to do it with my own children and my grandchildren… to make them feel that they’re capable – within their capability that they should try hard, because the world is their oyster. And I think that made a big difference,” she said in one of her interviews. Kazanjian spread her positivity and confidence to all women.

In addition to her accomplishments, she was one of the first women in the United States to work on board Navy submarines, destroyers and other vessels. She designed a submarine-towed buoy, which was used to calibrate sonar and her design helped raise navigational accuracy for submarines – the ones that operate below periscope depth.

In 1956, she worked on analog and digital programs including the development of navigational systems and the creation of the “Saturn” missile and the “Viking” space system as well as the “Avangard” project.

She began to work on calculating the flight of “Atlas” type ballistic systems designed for the Pentagon and designed specific guidelines that allowed her to hit the target at 10,000 miles. Her work was included in an extremely confidential collection, which only the country’s top officials were given access to and two years later, NASA used these calculations in order to launch satellites.

Anna Kazanjian Longobardo is currently retired and serves on various boards such as Woodward Clyde and Woodward Clyde Federal Services. The former vice chair of the Engineering Foundation Board as well as vice chair of the Bronxville Planning Board, she is still involved with the Barnard Science Advisory Council and Mechanical Engineering Advisory Board and currently lives in Bronxville, New York.

The lives and work of Paris Pishmish, Alenoush Terian and Anna Kazanjian Longobardo are truly inspiring. These three Armenian women persevered even in the face of adversity. When they weren’t heard, they spoke louder. They didn’t acquiesce to societal norms. They not only worked to advance their own careers, but they spent time to mentor, guide and inspire their students, colleagues and communities.

Together, they represent what it means to be powerful, intelligent leaders empowering women to fight for their dreams.