The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, accessible online models of Armenian cultural sites can transport Armenians to the Motherland from the safety of their homes. These 3-D models are available online via CyArk, a nonprofit organization committed to “digitally record, archive and share the world’s most significant cultural heritage and ensure that these places continue to inspire wonder and curiosity for decades to come.” The global breadth of their digital database has been used to educate on a multitude of histories and cultures, document the existence of threatened monuments, inform on-the-ground preservation work of ancient sites, and tell the stories of the people who still use them today.

CyArk has worked with the My Armenia Program at the Smithsonian Institution for their “Armenia: Creating Home Folklife Festival” in 2018, the United States Agency for International Development, the Ministry of Culture for the Armenian government, and trained many Armenian students from the TUMO Center for Creative Technologies in Armenia to document sites such as the Geghard Monastery, churches in Ani, the Areni-1 cave complex, and the Noravank Monastery.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Kacey Hadick, CyArk’s Director of Project Development over Zoom to discuss the increasing salience of cultural heritage sites which have been digitally documented and are publicly accessible online during this time.

He emphasized that it was the passionate and hard-working TUMO students — the bright fruits of Armenia — who documented the different sites, problem-solved to technologically accommodate their varied environments, and acted as dedicated translators and mediators between the CyArk team and the local Armenian priests and archaeologists.

Read also

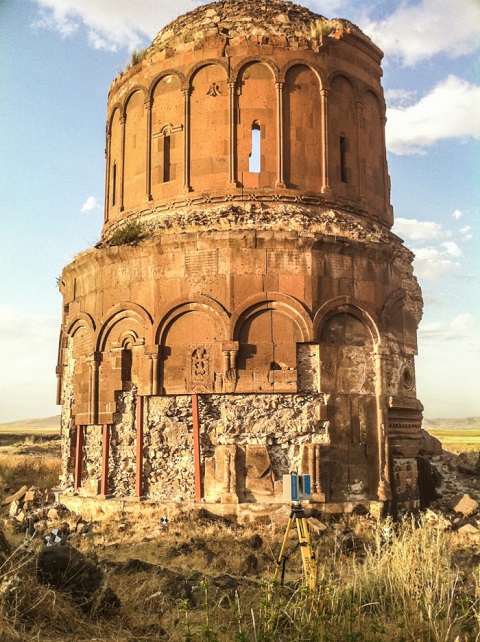

The young group of students completed the modeling with the assistance of the CyArk team through laser scanning in combination with photogrammetric documentation. The laser scanning contributes the base of these digital constructions by emitting countless pulses of light which travel through space until they hit a wall or object. When a pulse is reflected off of the surface back to the scanner, the scanner registers the location of the surface it hit, generating “this really dense cloud of points,” in a 3-D blueprint of the space. Then, photogrammetry is used, taking large amounts of photos of the space and overlapping them at common points while contributing color and texture to the model. Through using these two technologies in tandem, “in the same way that a tablecloth is draped over a table,” the quilt of photogrammetry photos are bent and draped over the shape of a space, generating a realistic 3-D model of a monument or structure.

These digital models are not only a window into the physical realities of the sites, but the living stories, traditions, and oral histories of those who frequent and upkeep them. Hadick explains, “These 3-D visualizations provide a medium for storytelling, just like the way a photo or a video can be used, like how a documentary film can provide a really powerful view and give a voice to the people who have a connection to that place… who populate it. I think virtual reconstructions of places can also serve that same purpose of providing a medium or a canvas,” through which one can tell the stories of the people who have formed relationships with the sites “who remember that place and can put it in context in the long history of times,” breathing life into them.

The power in these digital reconstructions is their ability to connect people during this time of such disconnection to the art historians, archaeologists, and priests who upkeep and use the structures, to the timeless culture and contested history the sites speak of, and to the landscape of Armenia. They have the capacity to connect us to a piece of our heritage when rich cultural experiences are so desired. Though “Virtual reality or 3-D models will never replace the feeling that you get when you go to these places,” due to their presence, smell, size, spiritual invocation, and place amidst Armenia’s geography, they are glimpses of Armenian beauty and wonder.

These cultural heritage sites are waiting in CyArk’s digital database to welcome us with open arms. Especially now when travel is less accessible, they exist at our fingertips to be seen, enjoyed and celebrated wherever we may be – a taste of Armenia from the safety of our homes.

The digital models of Ani, the Geghard Monastery, the Areni-1 cave complex, and the Noravank Monastery can be accessed on the CyArk website at https://www.cyark.org/explore/, and virtual tours of the Areni-1 cave complex and the Noravank Monastery with information from local archaeologists and priests can be accessed through the My Virtual Armenia application which can be found on Google Play or the App Store.

By Isabelle Kapoian

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

Main caption: Using a light scanner in Geghard Monastery