The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. When I was living in Chicago I went to a restaurant one evening where a local Armenian band was playing. It was a typical “kef” lineup: oud, guitar, dumbeg, and clarinet. As the boys started to tune up, they were asked what number they would begin with. One of the musicians suggested something, and the oudist played the first few notes of the melody to confirm the tune they were speaking about. They nodded at each other and then, instead of going into one of the typical Armenian or Turkish songs one would hear in such a venue…they launched into a heartfelt rendition of Ara Dinkjian’s composition, Picture.

At what point does an artist become a phenomenon? At what point, a legend? At what point do we stop discussing who influenced that artist, and start to discuss whom he himself has influenced? Although I am certainly not the first to realize or write about this fact, I want to note that in the case of composer and oudist Ara Dinkjian, it is certainly a fait accompli: Ara Dinkjian is a legend in Armenian music and has been for many years now.

His compositions, almost all instrumentals when done by him, have become international hits. (We might also ask, at what point does a song become a “classic”?) They have then been given lyrics in Turkish and Greek, and the resulting songs have also become international hits. Why in Turkish and Greek? In his early career (1980s) it seemed Ara’s music was gaining the most popularity in those countries, though he himself was born and raised in New Jersey, where he still lives. Perhaps the Armenian community was not ready for him in those days. He was ahead of his time. When it came to listening music, concert music, our community still could not think past Gomidas Vartabed and the classical school. The oud was proper in dance music where it had to battle for dinner-dance and wedding reception supremacy with the keyboards and modern pop styles that became popular in the 1970s and 1980s. The primary artist who did play the oud in a concert setting, George Mgrdichian, essentially made his fame by using that instrument to play the works of Komitas Vartabed.

Read also

I will not attempt to explain here the somewhat circuitous route by which Ara Dinkjian eventually became acclaimed by the Armenian public, but acclaimed he is, and in addition to the Turkish, Greek and Hebrew lyrics, his songs are now being given Armenian lyrics by the likes of Istanbul-Armenian singer Maral Ayvaz.

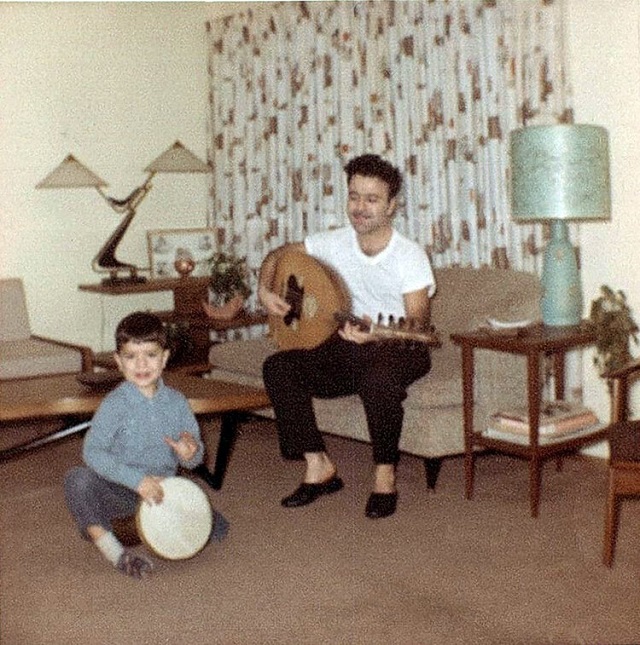

What is it that speaks to the hearts of all three peoples? Very simply, Ara grew up in the atmosphere of Armenian-American kef music, based as it is on the Anatolian folk music of Western Armenian regions like Sepastia, Kharpert, Dikranagerd, and Cilicia, where Armenian, Assyrian, Kurdish and Turkish traditions came together and on the other hand, the urban café music of Istanbul and Izmir, a style that was composed, performed, and propagated by generations of Greek, Armenian, Sephardic Jewish, Bulgarian, Gypsy and Turkish artists, in the mostly Greek-owned tavernas and gazinos (cabarets) of the city.

The same music was transported to these shores and performed at New England Armenian picnics and Manhattan’s Greektown nightclubs alike, and engendered generations of Armenian-American performers in what came to be known as the “kef” style. In the atmosphere of giants of the music like his father, vocalist Onnik Dinkjian, and Onnik’s often-time bandmates, oud master Johnny Berberian and clarinet virtuoso Hachig Kazarian, Ara grew up and absorbed sounds that he would recreate in his own compositions — compositions that spoke to hearts of Greeks, Turks, Kurds, Israelis, Arabs, and Armenians alike. In that sense, Ara has followed in the footsteps of the famed Armenian composers of Middle Eastern music in the Ottoman era, like Tateos Ekserjian, known as Kemani Tateos Effendi (1858-1913) and who was interestingly born exactly one hundred years before Ara Dinkjian and who also composed essentially listening music. When someone like Richard Hagopian, or even a Turkish or Arab oud player, opens a concert of Middle Eastern music, he often begins by playing Tateos Effendi’s famous Rast Peshrev. The younger Armenian musicians in Chicago chose Ara Dinkjian’s Picture.

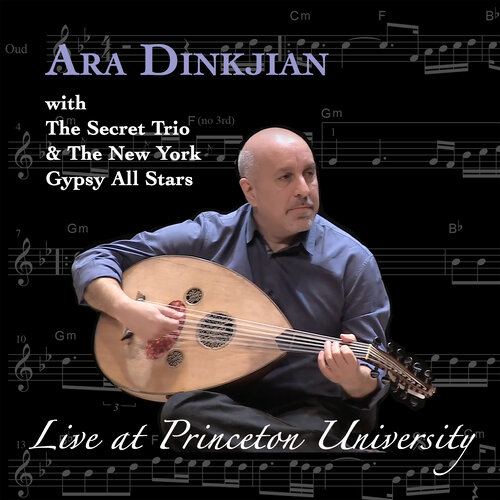

To hear the oud as concert instrument is also not new to Ara nor even to his predecessor George Mgrdichian. To find a famous Armenian composer who wrote his own pieces and performed them on the oud, we need go back only as far as Oudi Hrant Kenkulian (1901-1978), who gained great fame in the United States during his many trips here in the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, we can take the thread back even farther to the Armenian ashughs like Sayat Nova who both composed and performed — though, to their credit, they also wrote lyrics in a highly complex poetic form and sang them. Ara is not a singer, but his performances are complex in another way, as well as ground-breaking — they represent the fusion of Middle Eastern music with jazz and avant garde musical concepts. Although Souren Baronian and to an extent Chick Ganimian were the first to venture into that territory years ago, Ara (and his bandmates) break entirely new ground. But to see why that is so, let’s review his most recent release, Live at Princeton University.

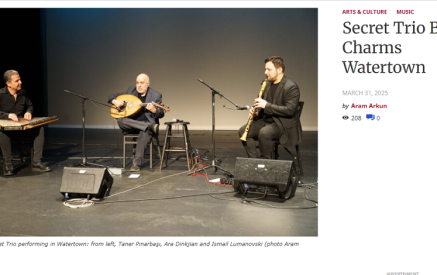

The set opens with the now-classic Picture. Like all the songs on this album, it is a Dinkjian composition. Ara, playing oud, peforms the first half of this live 2017 concert with his group “the Secret Trio.” The other members of the trio are Tamer Pinarbasi, a Turkish kanun player, and Ismail Lumanovski, a Macedonian Roma (Gypsy) clarinetist. The trio are based out of the New York area. All three musicians comport themselves well on this moving piece, which includes solos by Lumanovski.

Slide Dance opens with Pinarbasi’s innovative kanun playing imitating (to this critic’s ear) waterfalls or waves in the ocean. Amazingly, the effect is not just an auditory gimmick but harmonizes with the overall piece and is somehow at the same time executed in the 10/8 meter. (The song is a composition by Dinkjian in the style of an Anatolian Armenian line dance). Lumanovksi executes a number of glides and gypsy-like techniques, however his technique is used to create more of a jazz “sound” than a gypsy one. Both instrumentalists take solo turns, play off each other, Lumanovski plays a jazz inflected variation on the melody while Pinarbasi harmonizes (or rather, creates counter-melodies) to amazing effect, and they attempt a unison riff at one point. Dinkjian plays the melody at times and participates in some unison runs, but spends much of the piece seemingly sitting back and letting the other two musicians take the spotlight, but in reality he is playing the equivalent of rhythm guitar — something rather difficult to do on the oud, which does not lend itself to playing chords (it is traditionally a melodic instrument only). And then, all of sudden, he will punctuate the piece with a totally untraditional rapid attack on a few strings, between playing rhythmic chords on the oud. It is hard to put into words what Ara does here, but it is certainly far outside the box when it comes to oud playing.

Ara’s playing also recalls the fact that he has been a guitar player for many years as well, often playing rhythm guitar for his father Onnik’s or John Berberian’s albums in the 1970s. It is also obvious that none of this is written down, so the amount of virtuosity, as well as the amount of time they must spend playing together, is evident.

The Last Sultan is a new composition by Dinkjian. This impressionistic piece seems to paint a picture of the last days of the Ottoman Empire just after WWI. The melancholy tone of the song seems to recall Mehmet VI who was facing the end of his once powerful empire, while he himself was merely a pawn of the Young Turks, until the Damat Ferit Pasha government took over after the war and he became a pawn of the British. The piece, which is reminiscent of the compositions of Tateos Effendi, is played masterfully and delicately by the three musicians together.

The Invisible Lover, a well known Dinkjian composition, begins with Ara playing an exquisite, dark, introductory taksim in the Hijaz mode on the oud. The mostly straightforward interpretation of the pieces is however played by the three musicians with incredible unity and some interesting kanun effects from Pinarbasi. Lumanovski’s clarinet really shines in this piece, especially when he gets to take a solo. The interplay of the musicians here to create a piece that is more than the sum of its parts is incredible.

Sinanay, better known as the Greek popular song Hoppa Nina Nina Nai (Siko Khorepse Koukli Mou), is given its Turkish name here. This folk song, which is native to the Pontic Greek community of Niksar (just north of the once-heavily Armenian Tokat) was made popular in a Greek translation in the 1950s by Stelios Kazantzidis, whose father was Pontic Greek born in the nearby port city of Ordu. The musicians approach this song lightly, first led by Dinkjian on the oud, and then by Lumanovski on the clarinet with Dinkjian and Pinarbasi playing harmony, again, not typical for their instruments. After about a minute and a half of a slow, non-traditional, yet pleasant interpretation of the melody, the musicians break into a dance-like recreation of the popular Greek song, complete with imitation of bouzouki by Pinarbasi and jazz-type techniques from Dinkjian. Many of the pieces on this album could be described as Middle Eastern Balkan music that uses jazz style techniques rather than strictly a Middle East/jazz fusion, as the blues-inflected tonalities of American jazz are not usually heard here. But, midway through Sinanay, the band completely takes us by surprise, as Dinkjian and Pinarbasi start to create an aural effect of whirling on their instruments and Lumanovski goes into a solo on the clarinet with a mixture of klezmer, New Orleans jazz, Gypsy-influence, which sounds like it came out of one of the more trippy albums by the Beatles. Returning to the main theme of the song and closing out, this number gets an audible huge round of applause from the live audience, captured on the recording.

The second half of the half features Dinkjian together with a group known as the New York Gypsy All Stars. Pablo Vergara (keyboard), Panagiotis Andreou (bass) and Engin Kaan Gunaydin (percussion) play in this band along with Pinarbasi and Lumanovski.

The first song in this part of the album, a new composition entitled American Gypsy, is dedicated to Ara’s good friend, the late Haig Hagopian. Hagopian was a clarinet player in Armenian-American kef music for many years and was indeed known for a “Turkish gypsy” influenced style. The heartfelt melody and interpretation creates a nostalgic impression to memorialize days gone by in the Armenian-American kef scene where Haig Hagopian was a major figure. The playing on this song is more “kef” inflected than others, and yet also more American-influenced, showing who Haig was. Even when Dinkjian takes an oud solo, it is reminiscent of the oud style of Charles “Chick” Ganimian, with whom Hagopian played for many years. Throughout this whole album of his own compositions, Dinkjian rarely takes a straight oud solo. This one is played with deep feeling and soul, attributes that Hagopian highly valued, and which stand as a testament to Dinkjian’s friendship with the late clarinetist. Anyone who knew Haig Hagopian musically and personally would recognize the elements of this song that make it stand out as a tribute to him.

Pilaf is another new Dinkjian composition. The American inflection is strong here (with bluegrass or country-western influences), and the overall impression is that of Armenian-American life, exemplified by things like shared meals of pilaf. There is humor of course in that idea as well as in the musical ideas of the song. The “popping” of the the drums, the plucking of the oud and kanun strings and the way the clarinet is played, themselves give an impression of the bubbling of the boiling water for the preparation of pilaf. Listening to this, I could literally see family members dancing out the back door of their house, hands full of plates of delicious Armenian food and a bowl of steaming hot pilaf, for an outdoor family meal. Dinkjian, Pinarbasi and Lumanovksi all get to take nice jazz- or bluegrass-like breaks.

Common Spirit is a Dinkjian composition dedicated to the togetherness and peace between the world’s ethnicities and religions. The heartfelt melody gets the message across in something that sounds like it could be a pop ballad, a patriotic song, or a hymn. Dinkjian takes several great, brief oud solos in this one that have all the marks of his style but quickly return to a unified “common” expression with the other musicians. The melody seems to cry out for lyrics, but it would take a truly great lyricist to do it justice.

For Alexis, written for one of Dinkjian’s students, is an instrumental workout in a fast version of the 9/8 meter common in Anatolia and the Balkans. Lumanovski takes a clarinet solo which is backed by strange, echoing, moody, perhaps rock-influenced background sounds from the rhythm section, ending with a bass solo. While the melody is relatively not complex, it is difficult to perform because of the meter and the mode (Karjighar) in which it is written.

The final cut, Anna Tol’ Ya / Homecoming is a medley of two great Dinkjian compositions. The first is obviously a play on words for Anatolia, while the second is a popular tune known often by its Greek title Dinata, Dinata. The band goes into full kef mode for this track. I would be surprised if people weren’t dancing in the aisles. Ara takes a nice oud solo, but as always gives a lot of room to his bandmates. Pinarbasi’s kanun taksim is excellent on this track, with some unorthodox melodic progressions and jazz influences. Following that, the band goes into Homecoming, causing the audience to clap along. The contrast between loud and boisterous dance music alternating with a soft, almost chamber music interpretation is again seen with this tune. Lumanovski is given a solo where he shows off his Gypsy-style clarinet chops. The dance beat returns, again the audience claps along, and bursts into applause at the finish.

Ara Dinkjian, who has played these compositions of his countless times, manages to create something new with this album. His interpretations, along with those of his bandmates – especially Pinarbasi and Lumanovski – show an impeccable musicianship, and a driving, passionate, ingenious gift for improvisation. These songs have become such classics that even their composer now approaches them in a different light. This album could have been titled “Dinkjian Plays Dinkjian” – and this time, Dinkjian has outdone himself.

For more information visit www.aradinkjian.com.

Harry Kezelian

Main caption: Ara Dinkjian and The Secret Trio