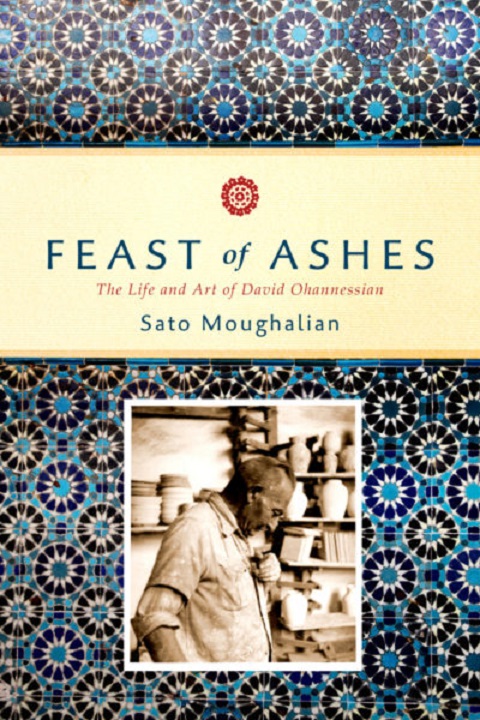

Feast of Ashes, by Sato Moughalian Redwood/Stanford University Press, 2019

Reviewed by Christopher Atamian

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

Read also

Born in 1884 in the village of Mouradchai outside of Eskishehir in Western Anatolia David Ohannessian led an idyllic childhood playing in the fields and enjoying age-old traditions and familial love. He would later move to Constantinople and Kütahya, marry and become a master ceramicist commissioned to renovate the tiles some of the Muslim world’s most celebrated mosques and monuments.

Ohannessian completed commissions that stretched half-way across the world to England and the United States. He would also get be caught up in the conflagration of World War I and the mad plan of the Young Turks to exterminate the Armenian people.

Marched into the desert in 1916 with his family, Ohannessian managed to not only survive but later, to thrive. In Palestine and later the State of Israel, he rebuilt his Kütahya studio, which had been known by the Gallic name Société Ottomane de Faïence.

The new workshop on the road to the Dome of the Rock would become a New Kütahya, where the ancient Ottoman ceramics tradition still thrives, displaying beautifully colored glazed tiles and pottery painted in every possible hue of the color palette. Along with a few other famed potters, Ohannnessian took in surviving Armenian orphans and founded an entirely new school: in Jerusalem today the name Armenian is synonymous with an entire artistic tradition.

His granddaughter, Sato Moughalian, the author of Feast of Ashes, grew up in the leafy New Jersey suburb of Highland Park surrounded by other immigrant families, many of them Jewish. Her parents had barely escaped Nasser’s nationalization of Egypt in the 1950’s and they now led productive lives, her mother an English teacher, her father an engineer. A lone beautiful vase made by her Grandfather David decorated a mantelpiece their suburban living room.

As a child Moughalian learned about World War Two and the Holocaust, but knew little of her own history. She studied hard, attended Barnard and became a renowned flautist and founded the Perspectives Ensemble, that contextualizes the work of musicians and visual artists. When her mother died, she left a Memory Book of sorts behind for Sato and her cousins. Sato took down the beautiful blue glazed vase from its perch once more, and thus began a multi-year quest to learn about her family’s history and in particular that of David Ohannessian, master ceramicist:

“But my grandparents had survived. And my parents had survived. They had made a giant leap of faith and traveled to yet another foreign country in the hopes that they could root themselves in a different kind of society—one that was free of constant threats, upheavals and loss. I came to see my grandparents’ fundamental task had been to keep their family alive. Not only had they done that, heroically, but they were also able, somehow, to take a centuries-old art form and give it a new life in Jerusalem…They went on to create a family of seven children, each of whom would add his or her gifts to the world.” (p7)

The journey took Moughalian around the world to Turkey, England, France, Israel, Palestine, Armenia and even back home to Brooklyn. Family history but also a desire for setting the record straight drove her forward as she explained to me: “Although Ohannessian’s story had been told, cursorily, in various art histories, those texts generally contained significant errors about him and portrayed him as a voiceless, powerless artisan, dependent on the benevolence of British Mandate patrons. This was a grossly incomplete description. I wanted to draw a clearer line from the first half of his career in Kütahya to the second in Jerusalem.”

Few books become instant classics, but Feast of Ashes comes close. Part family biography, part art historical narrative, part historical rendering of the Great Catastrophe, the book has received critical acclaim and was long-listed in the 2020 PEN American Literary Awards/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography. Moughalian’s prose is not literary per se, but it possesses an immediacy and sense of storytelling that draws the reader in from the very beginning. An example of Moughalian’s powers of description gives an idea of the complexity of her grandfather’s work on a fountain niche: “For the drum, Ohannessian inlaid molded tiles — crosses in shades of aqua and turquoise and stars in darker hues and white and circled the base of the cupola with another row of blue rumis. He arrayed the dome with mosaic tiles in the forms of eight-pointed rosettes, stars and crosses. On this curved ceiling, however, he altered the color scheme, glazing the crosses in white and stars in shades of blue.” (p222)

Moughalian’s effort deserves particular support for another reason: published in 2019, Feast of Ashes was just picking up steam when the COVID-19 pandemic curtailed her book tour. Among other cancelled dates, the author was never able to deliver the 2020 Dr. Berj H. Haidostian Annual Lecture at the University of Michigan. In private conversation, Moughalian draws a direct link between the events of 1915 that her family underwent and the current attempt by an Azerbaijan and Turkey seemingly determined to repeat history: “I’m keeping a very close watch on the events in Artsakh. It’s crucial to speak up. It’s impossible not to think of the Genocide, the mass violence, deportations, and other expropriations of 1915-17, especially as Erdogan seems to have made explicit references to it.” Indeed with this terrible war currently unfolding in Armenia, the story of David Ohannessian’s survival is doubly important, and ultimately perhaps, doubly reassuring.

Main caption: Sato Moughalian