The Armenian Weekly. As the Armenia-Azerbaijan war grinds to a disastrous conclusion, Armenians around the world yet again feel abandoned and invisible. We have similarly fought not to be erased by more powerful groups in the California Ethnic Studies Curriculum. The conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh and the fight over California’s Ethnic Studies Curriculum may seem worlds apart, but this perception ignores how “over there” is never that far from “over here.” Most importantly, it ignores the entangled histories of white supremacy, ethnic violence and foreign policy at the core of the empire. Because of our unique position, Armenians have often challenged conventional categorization and been subject to erasure when they don’t fit within master narratives about religion, whiteness/non-whiteness, native/foreign. However, these erasures situate Armenian marginalization within a global racial field and demonstrate the need for more nuanced analysis and a liberatory and coalitional politics that sides with the weak, rather than the powerful.

For much of the past year, I’ve worked with a coalition of Armenian and West Asian American Ethnic Studies scholars to support Armenians’ inclusion in the California Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum, a course of study slated for inclusion in California secondary education. After being initially excluded entirely, subsequent curriculum drafts referenced Armenians solely in relation to genocide, then in relation to political upheaval in the Middle East, and finally as decrying other genocides and fleeing communism in an appendix. Pushing for the expanded inclusion of West Asian communities like Armenians, Arabs, Persians, Kurds and Assyrians within the main text of the curriculum, we have advocated for careful attention to the slippery racialization of people from this part of the world and worked to make sure a century of our stories in the US, and especially California, was not erased. I was proud to see the Armenian community galvanized; public comments from Armenian Americans were among the highest of any group.

However, the draft model curriculum exposed a microcosm of blind spots on the American right and left that especially impact Armenian Americans. Predictable critics on the right parroted Trump, coming out against an “un-American” curriculum that courageously exposes histories of white supremacy, indigenous genocide and chattel slavery. Meanwhile, Zionist organizations instrumentalized several Middle Eastern minorities like Armenians – often against our wishes – in service of a bad faith campaign to exclude Arab Americans (and only Arab Americans) from the draft. At the same time, many academics and politicians on the left used a few popular data points – like the ubiquitous Kardashians – to claim Armenians were unequivocally white, Christian and therefore globally privileged. In public comments, politicians repeated that Armenians were distracting from federally recognized minority categories – African, Asian, Latino and Native American – or diluting Ethnic Studies in favor of “multiculturalism studies.” One prominent academic even dismissed our efforts as “that inclusion bullsh*t.”

Rather than deal with this political maelstrom, in September, Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed Assembly Bill 331 entirely, casting doubt on the place of high school ethnic studies at all.

Read also

For Armenian Americans, this rebuff was especially devastating since it occurred in a moment of accelerating crises for our community, including the shattering of Armenian neighborhoods in the Beirut port explosion, attacks on Armenian churches and schools in California and the existential threat from the full-blown war with Azerbaijan and Turkey. Caught between more powerful coalitions – and categories – more often than not, we were ignored.

The conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh and California Ethnic Studies Curriculum may seem worlds apart. But they aren’t. The treatment of American ethnic communities in their countries of origin and their geopolitical stature have always informed claims to opportunity and inclusion in America. On the flip side, the way we treat ethnic Americans at home indexes how our foreign policies engage ethnic groups abroad. The way we do, or don’t, understand the world underscores how we narrate the lives of Americans of all backgrounds.

By the 20th century, the United States had exported enough of its racial theories that few parts of the world were untouched by them. In the nineteenth century, Armenians were central players in Ottoman dramas of difference, which intimately engaged American racism. Beginning in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire repeatedly banned Armenian migrants from leaving and/or returning to the Empire, especially those it could identify as having spent time in the United States. When concerned Armenians would return infused with “radical” American politics, the Ottomans colluded with the US government to strip Armenian American returnees of citizenship, alternately expelling, interning or slaughtering them. Explicitly linking Armenians to Chinese immigrants and Native Americans, the Ottoman state argued that Armenians constituted an undesirable, alien race, and replicated US settler colonial logics by displacing and exterminating Armenians in several waves of violence that culminated in the Armenian Genocide. In spite of humanitarian support, even those European governments not at war with the Ottomans in World War I followed suit, largely abandoning Armenian citizens, employees, colleagues and students.

In the United States, Armenians were both fetishized as persecuted Christians and marginalized as not quite white. White co-religionists who proselytized to them in the Ottoman Empire often excluded Armenians from Protestant churches, and prominent Americans like Alexander Russell Webb and Charles Henrotin, the director of the Chicago World’s Fair, were on the Ottoman and Turkish payroll, deployed to claim that massacred Armenians had simply gotten what was coming to them. In the 1920s, the US and European powers kowtowed to Turkish pressure to deny the Genocide in exchange for economic concessions, the prospect of oil rights and an alliance against Bolshevism.

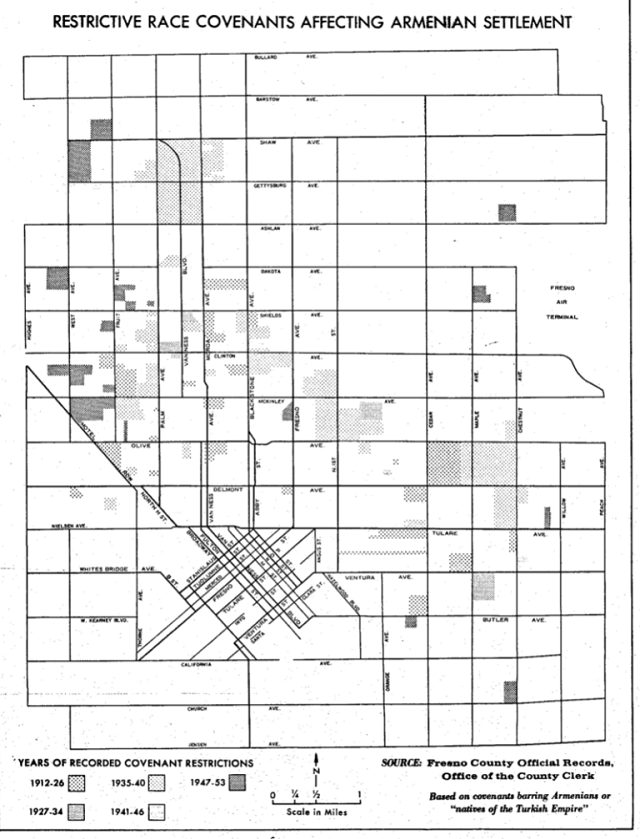

Restrictive Race Covenants Affecting Armenian Settlement. (Source: Fresno County Official Records, Office of the County Clerk, cited in Minasian, Armen Don. 1972. “Settlement Patterns of Armenians in Fresno, California” Master’s Thesis. San Fernando Valley State College. Northridge.)

American politicians insisted restrictive immigration quotas be judiciously applied to Armenians, and nearly every country in the Western hemisphere explicitly listed Armenians as undesirables. While naturalization cases, anti-miscegenation law, restrictive land covenants and informal school segregation contested Armenian whiteness in the legal sphere, slurs like “Fresno Indian,” “dirty Black Armenian” or “low class Jew” reiterated Armenian difference, especially in places like Fresno where they constituted a demographic “threat.” Sometimes mislabeled as “Semitic,” Armenians were denigrated as progenitors of the “Armenoid” racial type, a swarthy, hook-nosed archetype that encompassed Arabs and Jews, prevalent in KKK literature throughout the twentieth century. The threat of deportation loomed over Armenian Americans during the Great Depression, and the Bureau of Investigation—later the FBI—maintained files on the Armenian American community because of its suspect ties to co-ethnics in the Soviet Republic and orientalist assumptions about its inherent violence.

By the time I was born, the US government had quashed claims for genocide recognition and reparations for generations. It had also designated the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) and Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide terrorist organizations – classifications that helped land Armenians on terrorist watch-lists after 9/11. And while some Armenians emigrated to the United States as refugees following the Lebanese Civil War and pogroms in Azerbaijan, many remained discriminated against through programs like NSEERS (National Security Entry-Exit Registration System) and the Muslim ban.

Under Trump, these abuses have accelerated. In 2017, the U.S. State and Justice Departments conspired to quietly acquit Turkish nationals who beat dozens of Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish, Assyrian and Greek American protesters in Washington, D.C. Trump’s uncritical endorsement of Turkey and 3,000-percent increase in military aid to Azerbaijan, already armed to the gills by Israel, have led to dramatic military escalations in the region. And the lack of American press coverage of Turkish President Recep Erdogan’s denigration of Armenians as “leftovers of the sword” tacitly endorses his vision of a neo-Ottomanist empire built on ethnic cleansing. That Erdogan, his Azeri counterpart Ilham Aliyev and Putin lead repressive kleptocracies – who have not joined the chorus of world leaders congratulating Joe Biden’s electoral win – should demonstrate beyond any doubt the linkages among global dictators.

I don’t rehearse this litany of injuries as a way of scoring political points, and this narrative should not detract from the many instances of Armenian successes despite disadvantages. However, these shameful episodes have been suppressed by Armenians, as well as critics on the right and left, because they uncomfortably suture foreign and domestic concerns the United States has long swept under the rug: especially a deferred reckoning with whiteness, religious intolerance, greed and a global economy of suffering.

That Armenians, Arabs, Turks, Kurds, Persians, Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, Assyrians and other West Asian and North African communities have been racialized together, and belong within Ethnic Studies should be indisputable. Moreover, their inclusion is neither multiculturalism, nor importing into non-whiteness those who, critics claim, can and do pass for white. Instead, blind spots around these communities’ marginalization – and the cognitive dissonance their varied status produces – trace how oppression is enacted within a global racial field. More importantly, studying these communities in relation to other marginalized groups honors Ethnic Studies’ methodology and resists the interconnected erasure of Armenian American histories in the United States and abroad.

That the US Congress finally recognized the Armenian Genocide last year, and that justice-minded activists have finally begun paying attention to Turkish and Azerbaijani aggression are life-saving first steps. But they are not enough.

This moment of crisis requires a dramatic reconfiguration of the scope of our politics, and sensitivity to the blurry lines between past and present, home and homeland. The idea that the local and global are two separate and discrete spheres is an illusion, an imperial fiction that relies on received knowledge, ethnic exceptionalism and theoretical laziness. What’s happening on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border is not a conflict between Islam and the West. Nor is it a blood feud dating back to time immemorial, in which there are two equally matched and interchangeable sides. Instead, it is a war waged – and despicably won – by empires.

Armenians’ confusing and often contradictory place in American racial systems, foreign policy and humanitarianism represents imperial techniques that uplift and suppress categories for the sake of self-interest and convenience, often to divide and conquer. Our invisibility and abandonment in Artsakh – and Ethnic Studies – represent a failure of American education, analysis, activism and more damningly, of ethics.

However, these interlocking crises should be a call to action, for Armenians and non-Armenians alike, all those who subscribe to the modest and uncontroversial goal that fewer people live in fear. They require nuanced analysis, speaking truth to power, and unequivocally condemning violence, authoritarianism and imperialism wherever they occur. They require that we side with the weak and place contradictions at the center, not margins, of our research. Finally, they require a fundamentally different vision of liberation, in curriculum design as in foreign policy, that refuses the zero-sum logic that to uplift one community is to ignore another. Including Armenians and other West Asian groups within Ethnic Studies recommits to relational scholarship and coalitional activism, enacting a dramatic reimagining of our collective liberation.

For more information on the campaign for West Asian American Studies, please see: https://