BY HRATCH TCHILINGIRIAN,

Oxford

EVN Report — Long before the start of the armed conflict in Karabakh, the “authentication” of the history of the region had become the scholarly battleground of historians, political scientists, archaeologists, researchers and bureaucrats. The consequences of Soviet scholarship—particularly in the process of constructing histories—have been disastrous and continue to have a negative impact on how conflicting parties view “the other.” It should be noted that, even today, nationalist forces among the conflicting parties in the South Caucasus continue to exploit the propagandistic histories created in the Soviet period to shape public perceptions about “the other” or “the enemy.”

Read also

Despite the lack of linguistic and cultural similarities, Azerbaijani historiography has constructed an “Albanian connection” in the ethnogenesis of the Azerbaijani nation. Under this narrative, historic Caucasian Albania (which is not related to the modern-day country of Albania) is presented as the social, cultural and territorial predecessor of contemporary Azerbaijan; thus, refuting Armenian claims to Karabakh.[1] In recent years, references to Armenians in primary historical sources in the new editions of early chronicles on Karabakh published in Azerbaijan have been deleted or altered.

The roots of this historiography go back to the Soviet policy of “nativization” (korenizatsiia), whereby the construction of “national histories” in the Soviet republics was part of the official state “teaching” that national identity is inseparable from the given territory of a national republic. The “nativization” policy was intended to promote, for instance, national cultures and higher education, and increase the number of natives in the Communist Party structures within a given republic. In line with this policy, the “official history” of the majority ethnic populations and that of their republics became virtually interchangeable. The Soviet state’s political operational code was “one republic, one culture.” Thus, “Azerbaijani historians produced histories of ‘Azerbaijan’ in the medieval period based not on the historical facts of a prior national state but on the assumption that the genealogy of the present-day Azerbaijani republic could be traced in terms of putative ethnic-territorial continuity.”

While the ethnogenesis of the Azerbaijanis is a matter of academic debate, most scholars agree that Azerbaijan, as a national entity, emerged after 1918.[2] The debate on what to name the Azerbaijanis goes back to the late 19th century; the population of Azerbaijan, formerly categorized as “Turk” or “Transcaucasian Tatar” was formally re-identified as “Azerbaijani” in 1937. [3] Indeed, the founder of the first Republic of Azerbaijan, Mohammad Amin Rasulzadeh, admitted that naming the new republic Azerbaijan “had been a mistake.”[4] In June 2000, Nezavisimaya Gazeta quoted Vafa Guluzade, a prominent advisor to the President of Azerbaijan, affirming that “the very concept ‘Azerbaijani’ is an anachronism from the Soviet period. Our language is Turkish, and by nationality we are Turks.”[5]

In the Middle Ages, the territory of what is Azerbaijan today was inhabited by indigenous Caucasian peoples, which included the Christian Caucasian Albanian kingdom.

In the context of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, the “Albanian connection” has become a politicized issue of irredentism. Azerbaijani historians, by establishing a connection between present-day Azerbaijanis and Caucasian Albanians, in addition to providing a common national history, sustain the idea of ethnic continuity and presence in Karabakh and “demonstrate” that Karabakh Armenians are relatively recent immigrants to the region and thus a “non-indigenous” people living on ancient Azerbaijani lands.

Modern Azerbaijani authors omit references to Armenians who inhabited Karabakh before the Turkic invasions of the region. For example, the new edition of 19th century chronicler Mirza Jamal Javanshir’s Tarikh-e Qarabagh has deleted statements that “in ancient times [Karabakh] was populated by Armenians and other non-Muslims,” and most other references to the Armenian presence in Karabakh.[6]

Indeed, a retired colonel of the Azerbaijani Army, Isa Sadykhov, chairman of the Azerbaijani Association of Reserve Officers, took “comfort” in such “historiography”: “It is comforting to note that, in recent times, our historians and politicians have increasingly raised the issue of lands given to the Armenians.”[7] As scholar Shireen Hunter wrote, “Azerbaijan is bedevilled by [the Soviet] legacy” of reinterpretation of the region’s history and culture. “Indeed, many of the same methods of historical revisionism are used by the current leadership and nationalist leaders.”[8]

Reinterpretation of history has been intertwined with Azerbaijanis’ self-perception in contemporary times. An Azerbaijani diplomat in Washington, D.C., Elin Suleymanov, put this more succinctly: “Azerbaijan’s complex identity will continue to evolve based on how the past and its consequences are reinterpreted to deal with the present.”[9]

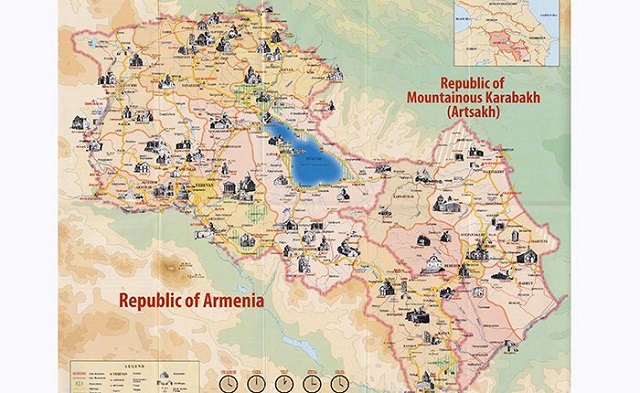

Over the decades, historians in Armenia have been engaged in refuting Azerbaijani historical claims, especially since the intensification of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict in the late 1980s, using evidence from prehistoric periods, primary medieval sources and modern scholarship on the region. But, Karabakh Armenians living on the land, rather than in history books, point to hundreds of ancient monuments, ruins of religious buildings, churches and monasteries as “living witnesses” to Armenian presence in Karabakh. Wholly innocent of scholarly learning, one middle-aged Karabakh farmer living near the 13th century Monastery of Gandzasar told me during fieldwork research: “This monastery kept us Armenian. The writings on these walls made us know who we are. There is a khachkar (cross-stone), the size of a car, on top of this mountain; our ancestors placed it there to indicate that this is Armenian land.” Ryszard Kapuscinski calls these khachkars “symbols of Armenian existence, or else boundary markers, …signposts. You can find [them] in the most inaccessible places.”[10]

The history of Christianity and the presence of the Armenian Church in what is today Karabakh is recorded by numerous historians starting in medieval times to the present.

A 1600-Year Christian Heritage

In the fourth century, soon after Armenia’s conversion to Christianity, the Kingdom of Albania (again, not to be confused with the Albania in the Balkans), which included the provinces of Artsakh (the future Karabakh) and Utik, converted to Christianity through the efforts of St. Gregory the Illuminator, the evangelizer of Armenia. Grigoris, the grandson of St. Gregory, was appointed the head of the Albanian Church around 330 A.D. He was martyred in 338 while evangelizing in the northeast region of the country near Derbent (currently in Russia’s Dagestan region). His body was brought to Artsakh and buried in a church in Amaras, in the Martuni region. In 489, King Vachakan the Pious renovated the complex and built a special chapel dedicated to Grigoris. Until today, the monastery of Amaras has remained one of the most important shrines in Karabakh and is considered a holy site for pilgrims.

The Albanian Church, like that of Iberia (until 608), having been established by Armenian missionaries, pledged canonical allegiance to the Armenian Church. At the wake of the controversy over the “dyophysite” Christology of the Council of Chalcedon, the three churches jointly convened the Council of Dvin in the sixth century and rejected the decision of Chalcedon. In 552, the seat of the head of the Albanian Church was moved from Derbent to Partav and an Albanian Catholicosate was established. The patriarch of the Albanian Church was given the title “Catholicos of Aghuank” (Artsakh and Utik) and received his ordination and canonical authority from the Catholicos of Armenia.[11]

From the 11th to the 13th century, more than forty monasteries and major religious centers were built in Karabakh through the patronage and efforts of the “Armenian princes of Artsakh.” As historian Bishop Makar Parkhoutaryants put it: “In time, these monasteries became ‘chimneys of enlightenment and a warm hearth of Christianity, incense-full houses of worship, protectors of faith, hope and love, defenders of nationality, language, literature, and holy places that unwaveringly defended the unique and orthodox doctrines of the Armenian Church.’”[12]

One of the most famous clans to have contributed to the revival of the Church and piety in Artsakh is the Hassan-Jalal princely family who, besides building the famous monastery of Gandzasar, have given several Catholicoses and bishops for the service of the church in Karabakh. The epitaph of Metropolitan Baghdassar, the last clergyman in the Jalal clan, who is buried in the courtyard of the monastery of Gandzasar, reads: “This is the tombstone of Metropolitan Baghdassar, an Armenian Albanian, from the family of Jalal the great Prince of the land of Artsakh, dated July 3, 1854.” Prince Hassan Jalal was also buried in the same monastery in 1261.

Starting in the 15th century, the monastery of Gandzasar became the seat of the native Catholicos of the Albanian Church. The existence of a separate Catholicosate in Karabakh, with its own autonomous religious institutions, attests to the importance of the region as a religious centre.

In the 19th century, the status of the native Catholicosate was drastically reduced. When tsarist Russia liberated Karabakh from Persian domination, Catholicos Sarkis of Karabakh, upon his return from exile, was demoted to the rank of Metropolitan by a decision of the imperial authorities in 1815. Metropolitan Sarkis headed the See until his death in 1828. After his death, upon the request of the Meliks (princes), Catholicos Yeprem of Etchmiadzin, in 1830, ordained Baghdassar, a nephew of Sarkis, Primate of the Diocese of Karabakh. He was ordained in the Mother Cathedral of Etchmiadzin. Thus, the Catholicosate of Karabakh was reduced, first to a Metropolitan seat and then to a diocese of the Armenian Church under Etchmiadzin.

Between 1820 and 1930, Karabakh was a hub of vibrant religious and cultural life. The Diocese of Karabakh and Swiss missionaries—the Basel Evangelical Association—operated ten schools in Shushi alone and founded the first printing press in the region in 1828. Church- and privately-owned printing houses published over 150 titles on biblical, theological, philosophical, scientific and literary subjects. More than a dozen newspapers and journals were also published in Shushi, such as ethnographer Yervant Lalayan’s Ethnographic Journal (the first volume). A remnant of this religious-cultural renaissance is the famous Cathedral of Our Saviour (built between 1868 and 1887) in the Ghazanchetsots neighborhood of Shushi.

Prominent scholars and teachers taught at the diocesan school in Shushi, the well-known monk-teacher Hovsep Artsakhetsi among them. He was the first Armenian philosopher on Synthetic Logic after the German school of philosophers, and wrote on logic and epistemology. His first work, First element of Philosophy: Logic, was published in 1840. Interestingly, there were also women monastics and deaconesses in Shushi, a rare phenomenon in the Armenian Church, who were involved with social and pastoral work under the aegis of the Diocese.

The Church in the Early Soviet Period

In 1923, when Soviet rule was established in Mountainous Karabakh, the Armenian Church was the first national institution to face monumental obstacles as a result of the growing Soviet pressure on religious institutions. The Armenian prelate of Baku, Bishop Mateos, in a letter dated November 3, 1924, addressed to the Supreme Religious Council in Etchmiadzin, reports that, despite the “state’s general decree on freedom of conscience and religious services,” local communist leaders are taking violent and extreme measures against the priests and the church. The people and the priests, “ignorantly thinking that these are state laws, are not daring to complain to the higher authorities… They have neither protection nor chief-prelate; they are left in doubt.” At the end of the letter, Bishop Mateos urges the Supreme Religious Council to send a prelate to Karabakh without delay and, in the meantime, asks them to write formally to the central authorities in Karabakh “to bring to their attention the illegal acts of the regional officials.”

In response to the recommendation of the prelate in Baku and in view of the growing persecution of the church in Karabakh, in 1925, the Catholicos in Etchmiadzin appointed Archimandrite (later Bishop) Vertanes as the prelate of the Church in Karabakh and dispatched him to the region to oversee the administration of the Church. Since the city of Shushi was out of bounds—the Armenian neighborhoods had been burnt down and the Diocesan headquarters closed—the new prelate chose the monastery of Gandzasar as his diocesan center. He visited the churches and monasteries in Karabakh and sent several reports to Etchmiadzin about the worsening conditions of the Church and the pressure on his own activities. The Commissar for Internal Affairs of Mountainous Karabakh closely monitored his activities.

In 1929, the now Bishop Vertanes, in a letter to Catholicos Gevorg V (1911-1930) in Etchmiadzin, laments the situation of the Church in Karabakh. “Everyday, dozens of churches and monasteries are being closed, clergymen are being imprisoned and exiled. …Please help us in this dire situation… all we are left with is 112 functioning churches, 18 monasteries and 276 priests.” In the meantime, the efforts of Etchmiadzin to negotiate with the authorities over the plight of the church in Karabakh did not yield any results. On February 7, 1930, Bishop Vertanes was arrested and jailed. Having spent almost two years in prison, he was released on January 1, 1932, as “the Supreme Court did not find [him] guilty of any crime.” Upon his release, he returned to Etchmiadzin “to recuperate” and was never allowed to return to Karabakh. Thus ended the activities and formal existence of the Armenian Church in Karabakh.

There were 250-300 priests serving in Karabakh and its regions from the late 19th to the early 20th century. In 1996, there were only six clergymen in Karabakh, including the prelate, Bishop Barkev Martirossian. For more than fifty years, there were no functioning churches or clergymen in Karabakh.

The Return of the Church in Karabakh

In March 1988, in an effort to pacify the popular uprising and demonstrations in Yerevan and Stepanakert, which had started the previous month, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union issued a decree on social-economic developments in Nagorno-Karabakh. This also created a climate for a cultural and religious revival in the region. Prior to the formal opening of the church, a renewed interest in religion and the church was created by the visits of preachers belonging to the Church-loving Brotherhood of the Armenian Church, who, starting in 1987, attracted a group of people who later “converted” and became “committed Christians.” This coincided with the time at the beginning of the “national liberation movement,” when, secretly, protest signatures were being collected in Karabakh. In early 1988, these new converts started to secretly collect signatures to have churches reopened in Karabakh (this was in addition to the larger signature campaign taking place for political and territorial changes). The signatures were presented to the Soviet authorities and a copy was given to the Catholicos in Etchmiadzin.

This campaign of the “believers” in Karabakh provided Catholicos Vazken I with additional leverage with the authorities to re-establish the long-defunct Diocese. In November 1988, he appointed Barkev Martirossian as Prelate of Karabakh. However, prior to the announcement, he had sent a young native-born priest, Fr. Vertanes Abrahamyan, to Karabakh with the returning delegation that had visited Etchmiadzin. Fr. Vertanes (renamed after the last Bishop of Karabakh) was the first clergyman to visit the enclave in decades. He stayed with believers and “secretly baptized people in homes because the OMON forces [Special Forces of the Soviet Interior Ministry] were spread throughout the regions and were chasing the youth who were active [in the Karabakh movement] and arresting them.” About seventy people were baptized, creating the core of workers who would later help in the reopening of the churches.

Soon after, the newly-appointed Prelate, together with four priests, came to Karabakh to establish the Diocese. The first church was formally reopened on October 1, 1989 at the Monastery of Gandzasar, after six months of preparatory work and reconstruction. On that day, the Bishop declared in his sermon: “Today is the beginning of our victories.”

The first task of the church leadership in Karabakh was to renovate churches and provide places of worship. Special attention was given to the opening of historically important monasteries, such as Amaras and Gandzasar. Between 1989 and 1991, the clergy were involved in active evangelization throughout Karabakh. Sunday Schools were established, teachers were trained to instruct the children and prepare them for baptism. Weekly lectures on religion and Christianity were presented by the Bishop at the Stepanakert Institute (later the Artsakh State University) and other schools where several hundred students would gather to hear the lectures. During the 1989-1990 academic year, a seminary was opened by the Diocese, with 12 students, but it closed in less than a year because of the war. Since all male citizens of Karabakh between the ages of 17 and 45 are required to serve in the army, all the students were conscripted. This has greatly affected the Church’s recruitment efforts to secure priests to serve the growing needs of the Diocese. The bishop was allowed to keep only three young deacons in his diocese by special permission of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR) Defense Minister. Another significant project of the Diocese of Karabakh was the establishment in Yerevan in 1990 of the Gandzasar Theological Centre, which produced literature and religious publications en masse for both Karabakh and Armenia. At least until 1995, it employed more than forty scholars, theologians, experts and support personnel, and is the publisher of the first Theological Journal in Armenia and Karabakh.

Within three years of its re-establishment, the Armenian Church had regained its legitimacy not only as a religious institution, but also as a national institution that fought alongside the people of Karabakh. Freedom of religion, ushered in by the collapse of the Soviet Union, coincided with the struggle for liberation. The evangelistic efforts of the church were eclipsed by the national aspirations of the people and the mass mobilization process for Karabakh’s independence. The Church was one of the first national institutions that was “reclaimed” by the people, even by those who were unbelievers, as a historically significant source of their religious and national identity. The functioning of their “mountain-protecting monasteries” and churches provided hope for Karabakhtsis who were facing uncertainties in their struggle, while the prospect of war with Azerbaijan was increasing.

In the early days of the Karabakh Movement, until the declaration of independence in 1991, the Church played a surrogate role as the advocate of the people and their rights, similar to the role of the churches in Poland and East Germany. In the absence of recognized political leadership, the Church became the unofficial representative of the people of Karabakh to the outside world.

Notes

[1] For a list of works, see note 21 on page 239 of this book.

[2] For a list of works, see note 24 on page 239 of this book.

[3] Azerbaijani historian Suleiman Aliiarov, ‘Bizim sorghu’ in Azarbaijan 7, 1988: 176.

[4] Touraj Atabaki, Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and Autonomy in Twentieth-century Iran. London & New York: British Academy Press, 1993: 25.

[5] RFE/RL Caucasus Report, Vol. 3, No. 25, June 23, 2000.

[6] Garabaghnamälär, Baku 1989.

[7] Zerkalo (Baku) May 5, 2001.

[8] Shireen T. Hunter, ‘Azerbaijan: search for industry and new partners’ in I. Bremmer and R. Taras (eds.) Nation and Politics in the Soviet Successor States. Cambridge University Press, 1993: 237. Cf. Graham Smith et al. Nation-building in the Post-Soviet Borderlands. The Politics of National Identity. London & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998: 50f.

[9] Elin Suleymanov, ‘Azerbaijan, Azerbaijanis and the Search for Identity’. Analysis of Current Events 13, 1, February 2001. Islam is another issue, for example, Hadjy-zadeh writes: ‘le nationalisme turc, qui est entré en conflit avec I’islam, a contribué substantiellement à modifier l’identité azérie’ (see Hikmet Hadjy-Zadeh, ‘L’Azerbaïdjan entre turcité, islam et modernité’ in T. Gordadzé and C. Mouradian (eds.) Etats et nations en Transcaucasie. Paris: Problèmes politiques et sociaux No. 827, Série Russie. La documentation Française, 17 September 1999. See also anthropologist Fereydoun Safizadeh’s presentation of post-Soviet Azerbaijanis’ “dilemmas of identity” in ‘On dilemmas of identity in the post-Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan’. Caucasian Regional Studies 3, 1, 1998.

[10] Ryszard Kapuscinski, Imperium. New York: Vintage International, 1994: 43.

[11] Բագրատ Ուլուբաբյան «Դրվագներ Հայոց Արևելից կողմանց պատմության (V–VII դարեր)», Երևան, 1981, 201-4.

[12] Մակար Եպս. Բարխուդարեանց, «Պատմութիւն Աղուանից» Հատոր Ա. Վաղարշապատ, Տպարան Մայր Աթոռոյ Սուրբ Էջմիածնի, 1902: 194.

This article is an excerpt from Hratch Tchilingirian’s, The Struggle for Independence in the post-Soviet South Caucasus: Karabakh and Abkhazia. London: Sandringham House, 2003, pp. 20-25; 155-167. The ebook can be freely downloaded at: https://oxbridgepartners.com/hratch/index.php/publications/monograph/524-karabakh-and-abkhazia