GLENDALE — The Artsakh war of 2020 may have had disastrous results, but it also led to unprecedented fundraising in the Armenian diaspora. Armenia Fund, a nonprofit nongovernmental pan-Armenian humanitarian organization in the United States, set new records during the war. After the war, questions began to be raised about the allocation of those funds. Maria Mehranian, chair of the board of directors of the Armenian Fund, Inc. from 2016, and in 2004-2008, provided information about the current situation and its context.

Armenia Fund: Background

The Armenia Fund was created over a quarter of a century ago in 1994, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, as a result of the Armenian Earthquake of 1988, Armenian independence, and the ensuing liberation war in Artsakh. It provides humanitarian aid and develops infrastructure for Armenia and Artsakh, including schools, hospitals, clean drinking and irrigation water systems, and highways.

Read also

Mehranian said, “Parallel organizations were born in the diaspora through the efforts of many concerned individuals. Armenia Fund Inc. was created originally in the United States to bring immediate relief to Armenia and Artsakh. It is a 501c3 registered with the state of California, and all its tax returns and financial information are placed on the website of the Secretary of State of California.” Its headquarters are in Glendale and it originally only worked in the West Coast. The East Coast of the US had its own board and separate structure from 1993 to 2018, but after the dissolution of the latter, the East Coast also came under the jurisdiction of the Armenia Fund.

The Armenia Fund is run by a board of 13 individuals, of whom 10 who are representatives of various Armenian-American churches or organizations. These include the Armenian Assembly of America, Armenian Catholic Eparchy of the US and Canada, Armenian Cultural Foundation, Armenian Evangelical Union of North America, Armenian General Benevolent Union, Nor Or Charitable Association, Armenian Relief Society of Western USA, Nor Serount Cultural Association, Western Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America, Western Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of North America. Mehranian said: “So our board members are the representatives of the stakeholders of our community. We have meetings quarterly, or more when needed, and most decisions are taken at these meetings.”

Mehranian, like the treasurer and secretary, is not on the board as a representative of any particular community organization but says she feels she is there on behalf of the Armenia Fund itself. She has always been involved in Armenian issues in her life, she said. Her maternal grandfather was the famous Yeprem Khan (Davtian), an Armenian freedom fighter who played an important role in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution. After graduating Damavand College in Tehran, she went to graduate school at the University of California, Los Angeles, to study urban planning. She eventually became the Managing Partner and Chief Financial Officer of Cordoba Corporation, which is a civil engineering, construction management and program management firm specializing in transportation, education and facilities, and water and energy. It is headquartered in Los Angeles.

Mehranian organized a trip for a delegation of California State Assembly and State Senate members to Armenia in 2001. During the visit, a series of meetings were organized with some members of the international board of the Hayastan All Armenian Fund to explore a blueprint for project development. Back in California, Mehranian began collaborating with the Armenia Fund for several years, and eventually was voted in as the chair of its board. After her election, during the 2004-2008 period, she reorganized the West Coast office, enhancing its operations through state-of-the-art software, data analysis, donor retention, and other development strategies.

Mehranian explained that because of her professional background, “I understand infrastructure. Professionally, it is a joy for me to contribute in thoughts, calibration, and the implementation and completion of projects.”

Though she had left the board after her achievements to focus on other things, around eight years later, when the idea of merging the East and West Coast Armenia Fund organizations was entertained, the Armenia Fund board in California thought her corporate experience would be helpful for this process. She was invited back and Mehranian accepted.

Operations

There are only two full-time employees of the Armenia Fund in its Glendale offices. Their expenses are raised, Mehranian said, through a standalone event held once or twice annually, which usually produces around two to three hundred thousand dollars.

While large and mid-scale donors contribute throughout the year, and some smaller donors also give regularly, the main method of fundraising is the annual Thanksgiving Day telethon, which began in 1996. The telethons usually focus on soliciting funds for a major project. Over the years, the cost of the telethon was gradually reduced from $700,000 to around $250,000, through lessons learned by experience, Mehranian said. In the last five years, expenses have fluctuated between $180,000 and $300,000, and they are taken from the total donations.

Projects are initiated in three ways, she said. Individual donors sometimes set up projects which they pay for, like a center against domestic violence, but want the Armenia Fund to supervise. Other donors have ideas for projects but want the Armenia Fund to set up the project as well as to implement it. The largest projects are requested by Hayastan All Armenian Fund, and Armenia Fund provides at least part of the money necessary to carry them out.

The All Armenian Fund projects generally are for things like roads or other expensive infrastructure. In the case of the Goris-Stepanakert road or the Vartenis-Martakert one, the cost was broken down so that each meter of road, at a cost of 200 or 250 dollars, could be sponsored.

There are also mid-sized projects which the West Coast office initiates. Twice a year Armenia Fund representatives from the US go to Armenia, once for a meeting with their implementing partner organization, Hayastan All Armenian Fund, and once to visit projects and participate in opening ceremonies. During these trips, Mehranian said, they also conduct their own need assessments. Among the ideas they came up with were projects for drip irrigation, solar panels and a maternity hospital in Stepanakert. The drip irrigation project cost half a million dollars, for example.

The money that is raised in the US for the large-scale projects, like roads, is sent in full to Armenia. The money raised for the smaller individual donor projects usually is kept in the US and sent as needed to Armenia and Artsakh, Mehranian said. The money for the mid-sized projects, like the drip irrigation one, is sent in parts. First a down payment is given, and then after a visit to the project and various reports about progress, further payments are released gradually. The money raised meanwhile is kept in a general account in the US.

All projects except those already set up by donors, whether large or small, are done through the approximately 20 person staff of the Hayastan All Armenian Fund. Before commencing, there are always memorandums of understanding for descriptions of projects, including budgets and timelines, sponsored by the Armenia Fund in the US. Bids are put out through the staff for projects. Three bids from three different contractors are required for each project, and the lowest bid is chosen, Mehranian explained. The staff there then supervise and report back on projects. Deadlines are set in the US and monitored. A third-party auditor is sent to Armenia to do financial and forensic reports.

The Hayastan All Armenian Fund takes seven percent of the total funds they receive for their expenses, Mehranian said, including overhead, program managers, construction people and labor.

She pointed out two advantages to working through the Armenian staff. First, there are strict codes for certification concerning construction, and not all organizations are subject to this level of scrutiny. Second, there is the advantage of having people familiar with local officials and conditions.

Mehranian gave the example of a trip of some doctors from a hospital in Glendale to Noyemberyan Hospital in Armenia. They were to stay 10 days to do volunteer surgeries but, all of a sudden, the local governor came and locked the hospital. The president of the hospital also refused to let the doctors come in, declaring that they would mess up the hospital. Mehranian immediately called the Hayastan All Armenian Fund which intervened and quickly made arrangements to resolve the impasse, allowing the doctors to do their work.

Corruption

The Velvet Revolution coincided with a scandal involving Ara Vardanyan, executive director of the Hayastan All Armenian Fund. He was arrested in July 2018 on accusations of embezzlement and misuse of funds. He apparently used funds for gambling, though he replaced at least part of these funds. This situation led to talk of closing down the organization or replacing it with a new one but then a new director, Haykak Arshamyan, was appointed in October of that year and worked to regain the confidence of the public, though in 2019 US donations were historically fairly low to the Armenia Fund. Furthermore, the auditing company for All Armenia Fund was changed.

Mehranian remarked that construction in general is a very complicated process. Often the project description and specifications change from design to construction. Even in the US, large companies often face performance problems and cost overruns. They present low bids and end up with numerous changed orders. In the recent history of infrastructure development in California, there are many examples of failure in large scale projects. Often contractors cut corners in favor of a shorter timeline and higher profit margin. In other words, she concluded, irregularities can happen anywhere.

However, she noted that having an international board of the All Armenian Fund with stakeholders from the global Armenian diaspora has reduced the possibility of corruption.

Artsakh War

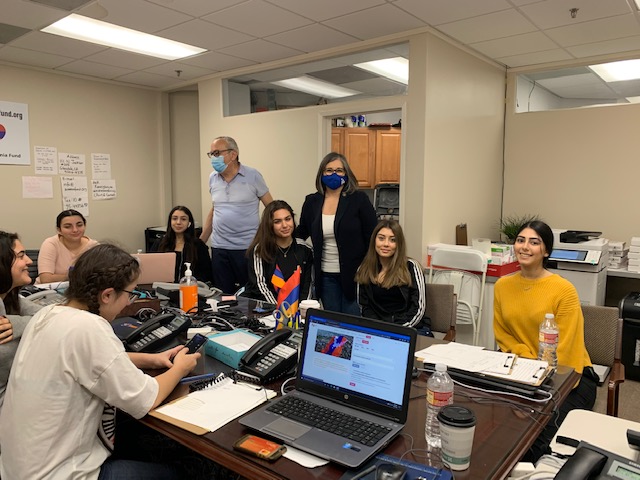

Everything suddenly changed when the war started. The message was spread by the Armenian government and many organizations that all donations to support Armenia and Artsakh should be via Armenia Fund in the US. The Glendale office was only staffed by two people, but there were 170 people on average walking into the office every day over two months to bring in their donations, Mehranian said, with lines extending down the street. It was unbelievable, she exclaimed. Between 2 and 2.5 million dollars was collected each day.

It was necessary to have 180 volunteers help. There were over 200 fundraising events, some virtual and some in-person, held during this period. Some 175 Instagram fundraisers were held, and 200 on Facebook. There were car show rallies, festivals, bake sales, jewelry sales and clothing sales, a petting zoo and even golf.

In addition to the regular Thanksgiving telethon done by the Armenia Fund, a special Armenia Aid Telethon was organized by an independent group of Armenians on October 10 which the Armenia Fund staff helped, and the $35 million it raised was given to the Armenia Fund. The Thanksgiving Telethon was announced in the beginning of November and 22.9 million dollars were collected from November 10 till the end of the month. Money is still coming in. Over 100 million dollars has been collected in the US so far, including this sum. Outside the US, 110 million was collected, according to All Armenian Fund figures.

During the war, money was sent by Armenia Fund in increments of 10 million. Mehranian said, “Every time we sent money had a specific memorandum of uses that we wanted, mostly for transitional housing, temporary shelters, food, generators and heating equipment. We were very specific.” Aside from money, Armenia Fund also sent certain types of medical equipment, especially wound related, such as suction machines and portable MRIs. From September 27 to December 18, 150 tons of goods were sent to Armenia in two major cargo shipments, along with 20 pallets of goods a week.

The war created an extraordinary situation, with Armenia and Artsakh facing an existential crisis. It led to the doubling of the size of the Armenia Fund database over the course of six weeks, Mehranian said. There were 175,000 individual donors, and the number of donations were higher, in the range of 250,000, because some people gave twice or thrice. “The reason they gave was the war,” she said.

She said that the fund did a statistical analysis and found that many of these donors had not previously donated, and were largely Armenians originally from Armenia. She said, “So it is a whole new universe of donors. Historically we have had a small number of big donors who give 1-3 million dollars, and then we raise another few million from large numbers of smaller donors. The average donor at the day of the [annual Thanksgiving] telethon gives 100 dollars. She is a woman between 35 and 55 years old. This is very different from what we have seen now.” The average amounts during the war were higher, but she speculated that they might be single-cause donors. Another unusual element was the millions of dollars that came from matches from corporations.

Finally, there were so many donations that the receipts for tax purposes had to be outsourced to a special mailing house, Mehranian said, which still is continuing to send them out.

After the War

The defeat in the war created a lot of despair and anger among Armenians who blamed the current government of Armenia, amidst a very politically tense environment. One point of controversy was the decision of the board of trustees of the Hayastan All Armenian Fund through a series of votes during the war to transfer over 100 million dollars to the Armenian government for emergency use and allocation. Arshamyan at a November 19 press conference declared that this decision was necessary because of a “force majeure” situation, and that the government largely was using the money to address the refugee problem plus healthcare.

However, meanwhile when social media spread reports that that some government officials received bonuses in this period, this led to rumors of misuse of funds, while the government, seemingly in disarray because of the preceding events, has not yet been able to provide detailed reports of its use of the money.

Even President Armen Sarkissian of Armenia in a December 6 statement declared that the government should consider eventually reimbursing the Armenia Fund for the aid and urged the government to release a detailed report on its use. Nonetheless, Sarkissian, chairman of the Hayastan All Armenian Fund board of trustees, had voted in favor of the transfer of funds during the war, according to documents released by the All Armenian Fund.

Arshamyan, the All Armenian Fund’s executive director, on December 18 pointed to the board’s authorization, and stated, according to azatutyun.am, that he asked the Ministry of Finance to provide a written report about the use of the transferred money but at that time had not yet received an adequate response. The All Armenian Fund, he further reported in a December 24 interview with Never Mnatsakayan of 1in.am, continues its own efforts to support refugees in Armenia, wounded soldiers, and families in Artsakh.

Mehranian declared that as the board of Armenia Fund in the US has the usual practice of visiting its project implementations every year, it expects that after covid-19 related travel restrictions are lifted, a small group of board members will visit Armenia to help organize information concerning the details of the expenditures of money raised in the US.

As far as future fundraising goes, the lessons of not just the wartime campaigns but of the past three or four years point to a shift in modality, Mehranian speculated. In the past, development directors would focus on a few big donors but now more funds are raised through websites and events. This means, she said, it is more and more important to have a good staff to work the database and expand outreach to large numbers of people.