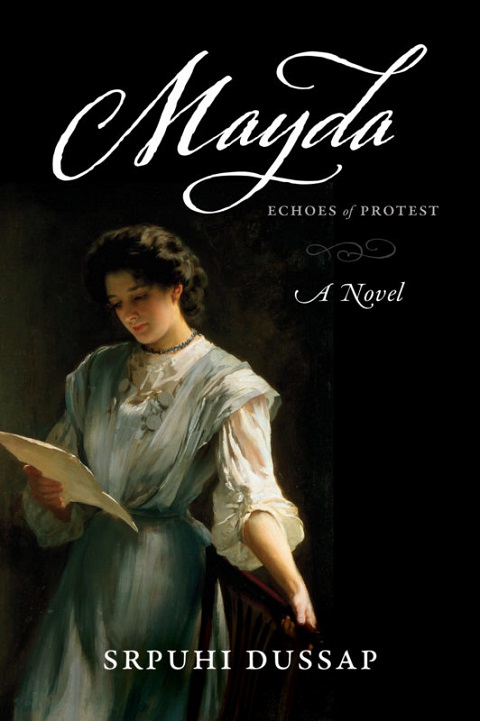

Billed as “the first Armenian feminist novel,” Mayda packs a wallop. Srpuhi Dussap’s book, beautifully written and surprising until its final pages, treats important political and social issues but never bores. Conventional by upbringing and somewhat weak-kneed by temperament, Mayda does a lot of growing up in Dussap’s 1883 epistolary novel. The chains that for so long bound women in all aspects of their lives at the time are eventually shattered as Mayda matures and follows the wise counsel of her older best friend and consort, Mme. Sira.

Mayda is born into a bourgeois Bolsetsi family and lives life with all the social advantages, discreet charms and privileges of the Armenian amira bourgeoisie — until her husband unexpectedly dies, leaving her penniless with a daughter, Hranush, to care for. Now Mayda must face the awful but undeniable fact that none of her society friends will acknowledge her anymore. For all practical purposes, she has been entirely stripped of any social standing.

Mme. Sira however will have none of her self-pity. She exhorts Mayda instead to be independent and to live her own life — not common for women of her social milieu at the time: “The past pampered you as a tender child. The present will make a woman out of you in the face of misfortune, giving you courage…Be as great as justice, as great as truth, as great as sacred love. Avoid darkness, avoid falsehood.“ Coincidentally this was basically the same advice that Dussap gave the great novelist Zabel Yessayan who visited her in her youth: namely, study, make something of yourself and then advocate for change in order to better women’s lot in society.

As the plot in Mayda twists and winds, Mme. Sira is not just a friend. She may be considered the conscience of both Mayda and Dussap as well, often railing against the unjust treatment of women under Ottoman law. The short-lived Ottoman Constitution of 1876 having done little to alleviate the harsh lot of minorities and woman, she declared, “What does the law do really?”

Mme. Sira writes Mayda in a long disquisition: “The law ties a noose around (a) woman’s neck that it tightens or loosens as need be. What is (a) woman before the laws of the most civilized nation in Europe if not the property of her husband?…Her lot is silence.” This seems obvious to us today, but at the time these words were quite remarkable. The illustrious Krikor Zohrab took great offense and condemned Dussap’s book.

Dussap herself was born into a wealthy Catholic Armenian family, studied in Europe, married a Frenchman and then devoted much of her life to philanthropic efforts and helping the Armenian communities spread across the Empire in any way that she could.

Thwarted love, betrayal, death, deceit: Mayda overcomes all these and more as she makes a place for herself and her daughter Hranush in a world full of trickery and evil. Mayda holds its own as one of the best epistolary novels to date. As morally relevant as Richardson’s Pamela and in places as devious as Laclos’ Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Dussap’s book — one of the first to be set down in colloquial Western Armenian rather than its literary variant — is written in simpler everyday language. Here’s an example of Dussap’s elegant and dramatic writing, in a letter from Mayda to Mme. Sira: “I was oppressed by the burden of my depression and the new responsibility fated by my condition. I was aimlessly flowing in the abyss of despair when your redeeming voice urged me to get up, take courage and ensure my daughter’s steps in the treacherous road of life.”

Dussap would publish three more novels that all center on the condition of women in society —Siranush (1884) and Araksia, or The Governess, (1887) — before abandoning literature after the death of her daughter Dorine from tuberculosis in 1891.

This edition of Mayda was published in 2020 by AIWA Press (Armenian Women’s Association), the tenth title in an invaluable series of translations of Armenian women authors. Previous books include Shushan Avakyan’s remarkable translation of Shushanik Kurghinian’s I Want to Live, as well as The Other Voice by the late Diane Der-Hovanessian, and Antonina Mahari’s My Odyssey. Also included are three works by Zabel Essayan: The Gardens of Silihdar, My Soul in Exile and Other Writings, and her seminal In the Ruins, a literary reporting of the horrors that the author witnessed in Adana immediately following the 1909 massacres. These publications are of particular importance as they make Western Armenian literature available to the English-speaking public. They rescue a part of Armenian and Turkish history that is vital to understanding everything from the psychological and economic mores of Ottoman society to the eventual Armenian-Turkish conflict which led to the Aghed in 1915-1923.

Finally, the works have strong literary value in and of themselves: one hopes that Mayda, for one, may soon be part of all university curricula that examine 19th century feminist writings. Kudos go to Nareg Seferian for his precise and flowing translation of Mayda — a book that everyone should read, whether their interest lies in feminism, Armenian Studies, or simply good literature!

Purchase Mayda: https://aiwainternational.org/product/mayda-the-first-armenian-feminist-book/