Introduction

When it comes to the South Caucasus, Iran is historically and geographically a crucial regional actor alongside Russia and Turkey. To assert its influence in the Nagorno-Karabakh/Artsakh conflict, Tehran had offered to mediate between Armenia and Azerbaijan on various occasions, but its efforts were unsuccessful due to the lack of interest of the conflicting parties. Iran’s interest in the region was a reflection of its balanced foreign policy towards the region and in favor of the status-quo.

Even though Iran has publicly declared its support for Azerbaijan’s “territorial integrity,” Tehran has been suspicious of Baku’s rapprochement with Tel Aviv. However, the recent war limited Iran’s options, so Tehran could not intervene in the conflict in favor of Armenia out of concern that this would antagonize Turkey which was directly involved in the war. This article will analyze the domestic and regional factors that limited Iran’s options during the war and whether Iran has been sidelined after the armistice and lost its influence over the region. These domestic and regional concerns and factors were interconnected. That is, the cheering of Iranian Azeris for the advancement of the Azerbaijani army in Artsakh was related to the growth of Turkish influence in the South Caucasus. From the Iranian perspective, any prolongation of the war would have a spill-over effect and give Western powers the pretext to use the “Azeri card” to destabilize Northern Iran. For this, Iran welcomed the outcome and joined with the winning side to gain a share from the “spoils of war.”

Read also

Why were Iran’s options limited?

In an exclusive interview with the Armenian Weekly on January 22, 2021, Dr. Hamidreza Azizi, a visiting fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), said, “Iran was always in favor of preserving the status quo, as it would guarantee a sort of leverage over both Yerevan and Baku. However, Iran never officially recognized the Armenian-controlled lands in and around Karabakh as an independent entity, but as territories belonging to Azerbaijan. As such, when Azerbaijan decided to resort to the military option, Iran could not condemn Baku or pressure it to stop the move, as it was seen as an attempt by the Azerbaijanis to retake their lands.” Over the past three decades, Tehran benefited from the Armenian control of the border area and enjoyed extensive cooperation with Armenia in these territories, including the establishment of a hydroelectric plant that serves Iran’s border regions. However, given the domestic, regional and military balance of power on the ground, Iran was isolated and left with no option but to revise its policies during the war. Dr. Azizi argues that Iran’s position toward the recent conflict was basically “reactive,” not pre-planned or an active change of approach toward the conflict.

Iran has always been suspicious of Israel’s intentions in Azerbaijan. There have been recent high-ranking official meetings between Azerbaijan and Israel during which both sides signed economic, security and military agreements. Moreover, Israel used Azerbaijan as an intelligence base to spy on Iranian military activities in Northern Iran. Azerbaijan was one of the first countries to buy Israeli long-range, precise and tactical kamikaze drones. In 2016, when Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu visited Baku, he revealed that Azerbaijan had bought $5 billion worth of Israeli weapons. These developments raised alarms in Iran, because a strong Azerbaijan under Israeli influence is a threat to Iran’s national security and territorial integrity.

With the outbreak of the war in late September, demonstrations erupted in Azeri majority cities in Iran (ethnic Azeris make up about 25 percent of Iran’s population) demanding active support for their ethnic kin on the other side of the border. The war had already fueled a sense of Azerbaijani nationalism inside northern Iran. Tehran feared it would be dragged into the Armenian-Azerbaijani war. According to Brenda Shaffer, an expert on minorities in Iran, the return of Azerbaijani control over the border with Iran creates additional opportunities for direct interaction between Azeris in Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. Aliyev’s first trip to the newly captured territories included a visit to the Khudafarin Bridge (which connects the Araxes River and links to Iran). The raising of the Azerbaijani flag there can be interpreted as a political message. Tehran knew the symbolism of this ceremony, which seemed to also generate enthusiasm among Azeris in Iran. For this reason, Iranian officials and diplomats took a “pro-Azerbaijani” stance in public, and it was not surprising that the Iranian Supreme Leader made announcements saying “Karabakh is a land of Islam” and congratulated Azerbaijan on “liberating its territories from the occupation.”

During the war, Iranian diplomats warned about the presence of Turkey-backed mercenaries in Artsakh. On October 6, Ali-Akbar Velayati, foreign policy adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, said that Iran would not tolerate “terrorists who are being used by USA and Israel” to be based near its borders. The Iranian government took measures to reinforce security around the northwestern borders and warned the conflicting sides about possible spill-over of the conflict to the Iranian territory. According to Tehran Times, “Iran has deployed additional troops and (heavy) military equipment along its borders with Armenia and Azerbaijan in an effort to prevent any change in the geopolitics of the region and international borders.” Officials from the “Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps” such as Brigadier General Abbas Azimi, Commander of the Air Defense Forces and Commander Brigadier General Mohammad Pakpour warned and stated that any shift in border geopolitics (that is, a change in the internationally-recognized borders of Armenia or Iran) is a red line for Iran. Also, what the mainstream media had failed to portray is that Iranian diplomats, despite congratulating Azerbaijan, continued calling for the peaceful resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Thus, unlike the Azerbaijani and Turkish sides, which claim the conflict is resolved, Iranians were aware that after the armistice, the Artsakh conflict was temporarily frozen.

Another factor, on a regional level, that limited Tehran’s options from taking an active role in the conflict, was the increase of Turkish influence in the South Caucasus. Turkey and Azerbaijan are important trade and energy partners for Iran. Both Ankara and Tehran also cooperate against the Kurdish insurgency in the region, and they face the same regional rivals –the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Turkey is also a useful conduit for mitigating the effects of unilateral U.S. sanctions. At a time when Iran was being squeezed by the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign, it could not afford to alienate Turkey. Iran was worried that this conflict would trigger Turkey’s proactive policy of supporting Azerbaijan and give Ankara a larger stake in the future of the South Caucasus. As the war ended with Azerbaijan’s military victory, it was clear that the Baku-Ankara alliance had been radically strengthened and that Turkey was going to stay in Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, the armistice of November 10 gave Turkey leverage over Nakhichevan, and as such, Turkish entrepreneurs did not need to pass through Iranian territory to reach Asian markets by land.

All these factors have shaped Iran’s policy towards the conflict of Artsakh and exposed Iran’s limited options. However, after the November declaration, Iran realized that it may lose its influence over the South Caucasus and therefore has to react.

Prospects: Has Tehran lost its leverage over the South Caucasus?

Tehran has welcomed the end to hostilities in Artsakh, regardless of the outcome. However, one should note that Iranian leaders are cautious and worried. Tehran felt ignored both by Ankara and Moscow in setting the post-war security arrangements in the South Caucasus. The Tehran Times raised a crucial question, “Why did the leaders of Russia, Azerbaijan and Armenia decide to keep Iran in the dark about the ceasefire agreement while Iran shares long borders with both sides of the war and was directly affected by the conflict?” With its limited options, Iran’s passive diplomacy in the recent war cost it to lose its important transit role in the region. Based on the November 10 declaration, Azerbaijan’s exclave of Nakhchivan will be connected to Azerbaijan proper through a trade route passing from Southern Armenia, possibly the strategic Meghri region. While there are no indicators that Iran was involved in the drafting of the declaration between Armenia and Azerbaijan, one thing is clear, that Tehran tried its best to keep its border with Armenia untouched.

Now that Turkey has established itself in the region, and Israel, through this war, has succeeded in politically isolating Iran, Tehran is concerned about being economically isolated too. Iranian state-sponsored media have already warned that Iran could face commercial losses from the change of control of the border areas. In 2005, a pipeline around 1,700-km-long (1,056-mile-long) between Baku and the Turkish port of Ceyhan started its operations. Even before the imposition of sanctions on Iran, these pipelines replaced the Iranian gas exports with Azerbaijan. Energy security has consolidated Turkish-Azerbaijani trade relations as well as those two states’ ties with Europe; now the oil from Baku is shipped from Turkey to European states through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline.

Moreover, the current “ceasefire agreement” will hurt Iran’s economic interests. Until now, land connections between Azerbaijan and its Nakhichevan exclave passed through Iranian territory. As Dr. Hamidreza Azizi pointed out, the new route will diminish Iran’s image of being regional transit and its leverage over Nakhichevan. Meanwhile, Turkey, which borders Nakhichevan, gains land access to Azerbaijan proper without having to pass through Iran or Georgia, thus directly being connected to the Central Asian markets through Armenia. Within this context, it is important to mention that on December 15, Turkey and Azerbaijan signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) whereby Turkey’s crude oil and natural gas pipeline trading company BOTAS has recently opened a tender for a gas pipeline to supply Nakhichevan. The new supply route would sideline Iranian gas sales to Azerbaijan and comes as Ankara is trying to repair its relationship with the US. Thus Iran would lose its leverage over Azerbaijan.

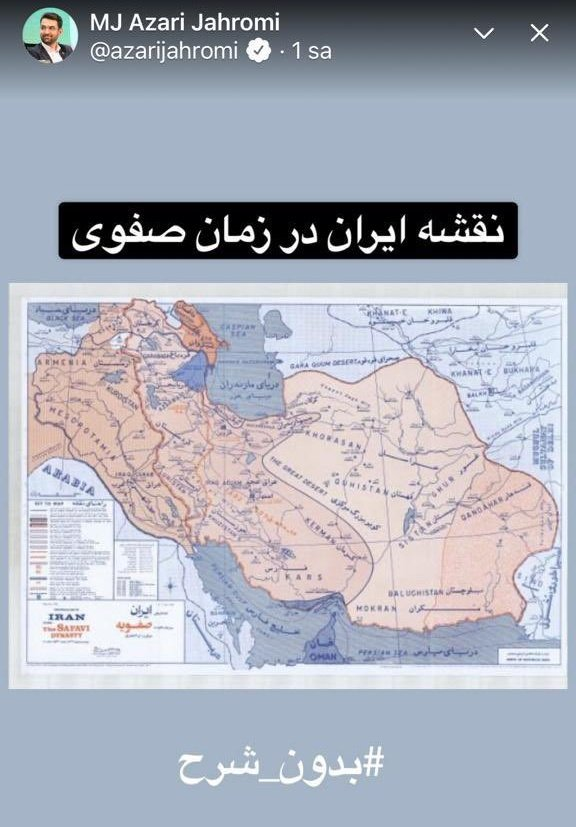

Adding fuel to the fire, on December 10 “diplomatic tension” broke out between Turkey and Iran after President Erdogan recited a poem in the military parade in Baku. Tehran deemed this as support for the secession of the Iranian territories populated by Iranian Azeris which pushed the Iranian parliament to pass a resolution condemning this act. Meanwhile, Iranian officials attacked Erdogan and posted on social media maps of the Iranian Safavid Empire claiming that once Azerbaijan was an Iranian territory. The geopolitical results of the recent Armenia-Azerbaijan war set off a discussion in Iran on its foreign policy toward its neighbors in light of what Tehran perceives as a serious geopolitical setback. The newspaper Tasmin, which is close to Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence, ran a series of articles analyzing the results of the war for Iran, including the possible future “threat from additional Russian troops that will be deployed close to Iran’s border with Armenia,” and Tehran’s perceived “loss of Armenia” due to now increased Russian and Turkish power. In one of the articles in the series, the author suggested that Iran should adopt a positive policy that would adapt to the current reality of the balance of power.

From a geopolitical and geo-economic point of view, Iran has lost valuable leverage over Azerbaijan and the region. On the other hand, as Azizi argued, “Turkey will be in a better position concerning east-west transit and economic routes, which could have major negative geo-economic implications for Iran. That said, Iran is already trying to get some positive outcomes from the new situation in the region.” Azizi believes that Iran’s official support for Azerbaijan’s military campaign seems to have opened up new opportunities for Tehran-Baku cooperation. Iran has already expressed a willingness to engage in reconstruction work in the newly retaken territories. There are also talks about Iran being part of multilateral economic frameworks in the Caucasus (what Erdogan has called a regional cooperation platform composed of Turkey, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, Russia and Armenia). The real question here that remains ambiguous is: how can Iran change its loss to a benefit? What is clear is that as Tehran lost its leverage over the region during the war, it may feel pressured to consolidate its relations with Armenia to contain Pan-Turkist influence in the north; however, under the current circumstances, will Iran antagonize Turkey? Iran’s new calculations may be dependent on the future geopolitical shifts in the region and how Russia reacts to them. For now, Iran would be favoring the current status quo with certain amendments that can serve its interests in the region.