On August 14, 2019, I swore an oath to become a citizen of the Republic of Armenia. It was a decision that felt so natural to me, but many of my friends and family wondered why. I’ve always felt compelled to give a knee-jerk reaction by replying “why not?”, but I knew that their remarks were not just some accidental occurrence and that they were genuinely curious. Indeed, other than having some visa-free access to some obscure countries, there seemed to be little tangible benefits for my citizenship. But deep down, it was much more than that. I never felt I should bother explaining why I did what I did. Until now.

My family was among the last Armenians to leave their historic homeland of Sepastia (today’s Sivas) and settle in Istanbul in the 1960s. Prior to that, they had lived on those lands for more than a thousand years. Theories as to when the Armenians settled in Sepastia tend to vary, but there is a consensus among historians that the bulk of them settled there under a pact with the Byzantine Emperor and Senekerim-Hovhannes Artsruni of Vaspurakan as an exchange of territories to prevent further Turkish incursions into the Byzantine Empire’s frontier. With that, in the winter of 1021, Senekerim-Hovhannes surrendered his kingdom to the Byzantines which effectively ended nearly a thousand years of Artsruni rule. As the Byzantine army moved into Vaspurakan, approximately 14,000 Armenians of Vaspurakan packed up their belongings and settled in Sepastia where Senekerim-Hovhannes was granted autonomous rule. Perhaps some of my ancestors were among those who settled from Vaspurakan to Sepastia at that time. Since then, my family probably never lived in Armenia proper. Nonetheless, it should go without saying that to say you’re Armenian is to say you’re from Armenia. It is acknowledging that at some point in time in your family’s history you once lived in Armenia proper. To many that should be obvious, but for other Armenians, their identity is based on theoretical grounds given how long ago it was that they moved out of Armenia. Regardless of it all, my family, just like many Armenian families, has kept their identity alive for thousands of years and are now able to tell their story. And in any case, some theories concerning where and why Armenians settled in and around Armenia are more concrete than others. We can all agree, however, that Armenians once lived on those lands with some degree of land and property ownership and in many cases autonomously, for better or for worse.

Fast forward to today: there are almost no Western Armenians left in their historical homeland. Most Armenians were forcefully deported, assimilated or massacred and are now living in foreign lands with various different passports in their possession. Armenians have been forced to adopt new customs, beliefs and identities and begin the process of starting and building new lives. Nevertheless, we adopted William Saroyan’s model of building a “New Armenia” and did whatever we could to salvage our identity as a people. This was the modus operandi for decades and almost felt like it was here to stay.

Read also

But things suddenly changed in 1991 and the unthinkable happened: Armenia became an independent country. The whole idea of building a “New Armenia” in the Diaspora became obsolete. We now had an Armenia we could all build, invigorate and develop. This opportunity would have probably been inconceivable for those who never got to see this moment.

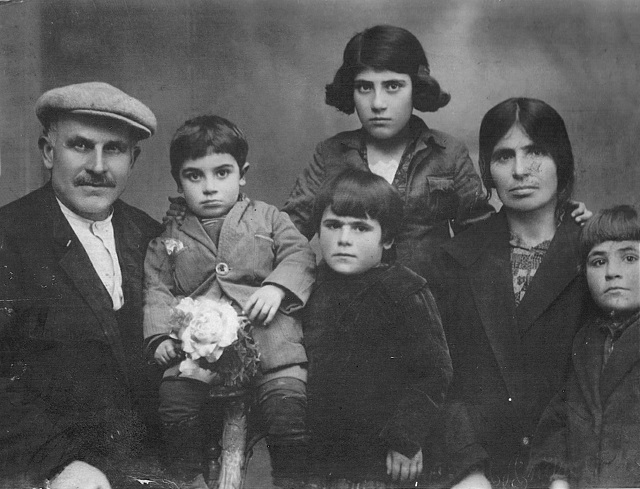

Great grandfather mentioned in the article on the left. My grandfather with a bouquet of flowers sitting beside him. The older woman on the right is my great grandmother. The younger girls are my grandfather’s sisters. The wife and husband are genocide survivors. This was my great grandmother’s second marriage since her previous husband and three children were killed and lost respectively during the genocide. Photograph taken circa 1931.

My family’s history differed from most genocide survivors in that they were among the rare few who managed to remain and continue living in their ancestral lands, but this time under the new Turkish republican rule. My grandfather, who was born and raised in Sepastia, would tell me stories about how his father, who lived under an increasingly hostile Turkish nationalist environment, would always revel in the idea of living in a free and independent Armenia. These mindsets were part of a dying breed that still felt a connection with Armenia. My great-grandfather was part of a bygone generation that openly discussed the prospects of an independent Armenia. But these dreams slowly disintegrated for many of these Armenians after the genocide, and most ended up moving to Bolis, ultimately integrating into the Bolsahye way of life. This lifestyle consisted of adopting an outlook on Armenian identity that was so different from the long-lost days of the national awakening of those Armenians living in their ancestral lands. They lost that connection forever and had to orient themselves to the new reality of living outside of their homeland.

It was no surprise that the main counter reaction to my citizenship journey came from the representatives of this part of my life. Many Bolsahyes looked confused when I told them I wanted to become a citizen. They felt and continue to feel that I am an Armenian at a cultural level and that Bolis has never been part of the Diaspora. I never understood why many Bolsahyes, including the late Hrant Dink, tend to disassociate themselves from Armenia, even not considering themselves members of the Diaspora, something I’ve always respectfully disagreed with. Bolis was never part of Armenia and to say that you’re not part of the Diaspora is to imply that you live on historically Armenian lands when in reality you were violently torn away from them. Indeed, the separation of Bolis and Armenia is not something new for that community. The Bolis Armenians, even before the genocide, always viewed themselves as outsiders and thereby disconnected from Armenia. While there were massacres happening in Armenia, many were ridiculed for writing poems about love and romance. In the aftermath of the Adana massacre in 1909, Rupen Sevag penned a scathing letter addressed to his Bolsahye peers, writing how alarmed he was at only being able to find details of the massacre in the European press, while the Armenian press in Bolis had only passing mentions of it, focusing more on romantic poetry and betrothal announcements. It goes without saying that this lifestyle comes from a life of privilege. They had the ability to distance themselves from Armenia, and that’s why they found it convenient to do so.

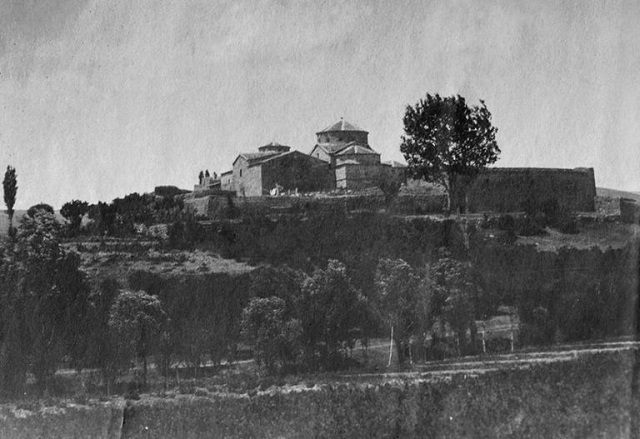

The monastery of Surp Nshan in Sepastia. Commissioned by Senekerim-Hovhannes’ son Atom-Ashot, parts of the monastery were made to look like Varagavank, the monastery that Hovhannes-Senekerim founded in Vaspurakan. Surp Nshan was named after a relic of the True Cross that was brought from Varagavank and housed at the newly built monastery. The monastery has been destroyed by the Turkish army and is now used as a military site. (Photo: Houshamadyan)

This is not meant to be a criticism of Armenians in Bolis. Indeed, many Diasporan Armenians throughout the world, despite all of their nationalist and patriotic rhetoric, are also disconnected to a certain extent from Armenia. For example, the materialistic obsessions of many Armenians in places like Los Angeles or Paris can be characteristically similar to the distractions the Bolsahyes indulged in back then. However, the Bolsahyes of today have succumbed to a unique narrative that was force fed to them by the Turkish government. Another reason why they may not want to identify themselves with Armenia is because the Turks made it impossible for them to make that association happen to begin with because of the genocide and acts of political, social, economic as well as many other forms of oppression that continued in the aftermath of 1915. Indeed, this partially explains why the Bolis community resorted to a communitarian form of living, working for the community by maintaining churches, hospitals, and schools above anything else. As such, they had to ultimately redefine their identity in a way that would appease Turks – that is, not taking Armenia into account at all, acting like it doesn’t exist, and considering themselves just citizens of Turkey. Implicit in the attempt at eradicating Armenian identity is the idea of the Armenian as “other” – lesser, sub-human – subject rather than citizen. The utter absence of human and civil rights within this scheme is as undeniable as the genocide. Yet, the Turkish government continues to unapologetically deny it, along with human rights abuses that continue to be committed against Armenians in a full-fledged assault that culminated this past year. The way in which such militaristic, political and psychological warfare is wielded against the colonized to destabilize any attempts at unity and resistance has been hauntingly effective across certain areas of the Armenian community. Second class citizenship cannot be achieved without the subjects’ acceptance of their own perceived inferiority along with the perceived superiority of the oppressor. The colonizers want to make you believe this and succeed in doing so when a fracture occurs between subjects who cease to identify their connection through their cultural identity and shared subjugation.

Frantz Fanon called this the colonization of the mind. It’s a theory that explains the subjugated mentality that many colonized people internalized without being conscious of it. That is to say that even after the many minorities become formally free from subjugation and dehumanization of some colonial power, they still carry with them the attitude of a colonial subject wherever they go. It explains why many newly-independent countries or communities still prefer emulating the former colonizer’s culture, beliefs and values. Fanon argued that the way forward would be to decolonize the mind and return to one’s liberated self. This can apply to all Armenians. As much as Armenians want to believe that we are free, independent and liberated, it’s not hard to see why we can still have a colonized mindset wherein we capitulate to the desires of those colonizers who want us to physically, mentally, and spiritually disassociate ourselves from Armenia. Every single moment that we distance ourselves from Armenia helps those who want to eradicate us to inch closer to achieving that sinister plan.

Indeed, there’s a steep hill to climb when it comes to this self-realization because Armenians have been dealt heavy blows throughout their history. On top of it all, much of their verifiable past has been lost in the dustbins of history. Family records, assets, places of worship, schools and other institutions have all been burned. Human beings can often harbor memories that they’ve never had or have long-lost and forgotten. However, the real loss would be giving up this history and doing nothing to retrieve it. This can be likened to a newly-discovered archeological site filled with a treasure trove of artifacts waiting to be dug up. Some of these treasures are out in the open and easily identifiable, while others need time, patience, and a tremendous effort to locate, unearth, and ultimately appreciate. It’s up to us as human beings to make that first step to this self-realization so that we can fully comprehend our past, present, and future as sentient beings on this planet.

When I became a citizen, I felt like I had retrieved something that was lost or taken away from me. I broke that chain of the colonizer and felt one step closer in fulfilling all that was lost in my family’s history. I became a citizen not only to fulfill my own desires, but the wishes of all those in my family who could not have ever had that opportunity. Indeed, this can be applicable for almost every Armenian. After all, the loss of Western Armenia was a loss for us all. The loss of our land also coincided with the loss of our identities as human beings. Hence, my decision to become a citizen wasn’t a nationalistic or patriotic one, but a personal one. It was something that I felt human beings must recover after centuries of deprivation and assimilation, and this was my way of resisting all those variables that wanted to make that recovery impossible.

After all, what is a passport but a booklet of bonded paper flanked by plastic? Its value is determined by those agencies that approve of it. And as we are constantly consumed with the idea of what others have to say about it, we often lose sight of what that little booklet may mean for us, and the values we instill into it ourselves are far more valuable to me than what any passport controller has to say about it. We put into that booklet the values we’ve attained throughout our lives. Among these values is that quest for identity and a sense of belonging. Sure, a passport is used to indicate where we are going, but it is also used to show where we come from. And, sometimes where we come from does not begin from the day of our birth, but a story that has traversed the depths of time for millennia.

To me, becoming a citizen of Armenia was a no-brainer. I am sure any Armenian who wants to be a citizen has their own unique story of becoming one themselves. Because in reality, we are all Hayastancis. To say we are anything but is to willfully succumb to the colonization of the mind. To create such a wedge between Armenians and refer only to those living under the Republic of Armenia as Hayastancis is to play into the hands of the colonizer. Therefore, to recognize this and adjust accordingly is the first step to self-realization and ultimate liberation. What astonishes me is how much we are allowing ourselves to dissociate with Armenia given our colonizers’ obvious delight. This trend only works in their favor as we further move towards the depths of an uncertain future.

Last known photograph of Senekerim-Hovhannes Artruni’s throne taken in the 1880s at Varagavank near Van. The throne was left vacated after Senekerim-Hovhannes surrendered his Kingdom to the Byzantines and was given land in and around Sepastia as compensation. Approximately 14,000 Armenians from Vaspurakan moved to Sepastia. The whereabouts of the throne are unknown but it is believed to have been lost during the genocide. (Photo: Public Domain/Library of Congress)

It is no coincidence that I write this article in the winter of 2021, because this winter marks the 1,000th year anniversary of when Hovhannes-Senekerim, due to the invading Turkish threat, surrendered his kingdom to the Byzantines and had tens of thousands of Armenians move from Armenia proper to Sepastia. As mentioned earlier, my family may very well have been among those who fled their homeland. Yet this story hasn’t changed and is eerily familiar. The issues Armenians faced exactly one thousand years ago are hauntingly similar to the issues Armenia faces today. Armenia still has to deal with the familiar existential threat of Turkish invasions and the prospect of losing our sovereignty. However, the one thing that can be changed is our response to this intimidation. Do we pack up and leave like the Vaspurakan Armenians did a thousand years ago? Or do we remain, resist and rekindle our connection with our homeland in order to further strengthen it? The choice is ours.

As Armenia continues to face the new but ever so familiar reality of coping with the aftermath of a war that can credibly be considered a genocidal attempt against its sovereignty, it is now more important than ever to consider the prospect of engaging with Armenia at this level. This is key to the progress of a nation, but also the progress of an individual. As we engage with ourselves as Armenians, we are simultaneously rekindling our connection to our common humanity. Armenians throughout the world have come a long way to make that happen. It is imperative for them to seize the moment and make the most of it because, at the end of the day, true liberation and independence comes from the mind above anything else.

Editor’s Note, February 25, 2021: The original version of this incorrectly portrayed the monastery of Surp Nshan in Sepastia. It has been updated with the correct image.

Garen Kazanc

Born in Paris to Armenians from Turkey, Garen Kazanc moved to Los Angeles at a young age, where he attended and graduated from the Armenian Mesrobian School in 2006. He received a B.S. degree in sociology from Cal State Los Angeles. He has been an active member of Hamazkayin and the Armenian Poetry Project and has contributed articles to various Armenian newspapers and media outlets.

Main Photo Caption: The author holding his newly assigned passport