The Armenian Mirror-Spectator.

By Arpi Sarafian

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

While quintessentially “Kardash”ian in its focus on the effort to create an alternative world, COLLABORATION, the latest in the series of Kardash Onnig’s ongoing Baraka Project, is also delightfully playful and colorful, attributes one does not typically associate with the artist’s work. The reproductions of the vividly colored pages of the children’s books — which Onnig, in collaboration with Vazo, an artist friend from France, salvaged from recycling bins, whitewashed “blank” and gave to children to draw and color, to “in effect start a new book” — put the spotlight on the children who, by the artist’s own admission, have become central to his creativity.

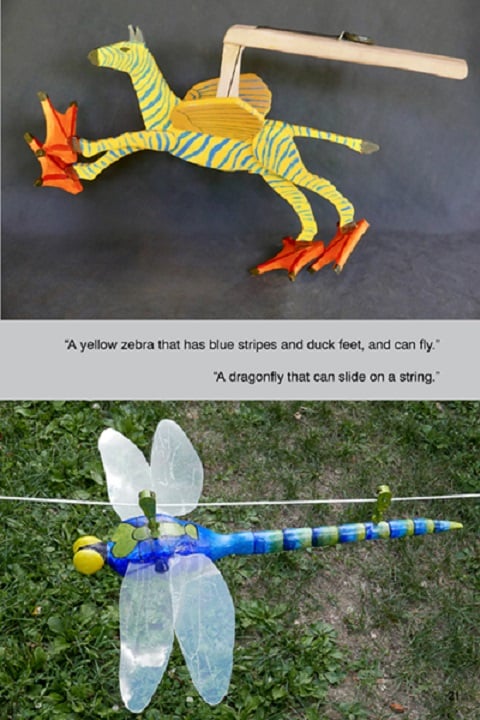

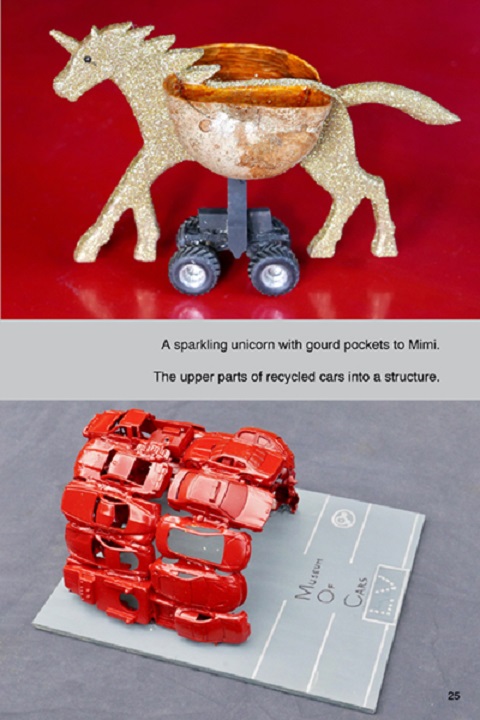

The book gives the reader a wonderful feeling of lightheartedness. One turns its pages in anticipation of yet another pleasing image of the artwork of the children it celebrates, or of the toys, the making of which has taken center-stage in the artist’s creative endeavors. A yellow zebra with blue stripes, an orange dragon, a sparkling unicorn, a green sea turtle . . . all burst with color and ingenuity. Making toys is “rewarding, fulfilling,” confesses Onnig. Indeed, “We The Children” give the artist hope for the future of mankind: “I have given up on grown-ups and instead concentrate on helping children.” Onnig is eternally optimistic and has unwavering faith in his vision of a more humane and compassionate world.

The handsome little volume also features the artist’s latest creations. The photographs of the “new finished work” Onnig has carved from a large beech chunk are incredibly appealing. Interspersed throughout are the reflections of artists of different backgrounds on their lifelong relationships with Onnig. The exchange between Onnig and Uli Boege, a friend artist of German descent with whom Onnig has enjoyed 53 years of intellectual collaboration, is especially illuminating. The two pals’ extreme positions on the women’s movement, on Nietzsche’s Dionysian Vision of the World and on much more, invite the reader to explore her own views on these controversial issues. Also included are short narratives of “a quintessential moment,” a unique personal experience the artist has asked visiting women to share “as part of an ongoing study to better understand the concepts of spirit and soul.”

With the Baraka Project, Onnig extends the concept of creativity into his collaborators whose very willingness to contribute evidences the respect they have for a guy that some dismiss as a “lunatic” with an unattainable vision of an “impossible” world. With his initiative, the artist aims to “connect people and experiences across the nation and internationally.” “It is an honor to have been selected as a visiting artist-in-residency at Baraka Center for 3-D Experimentation,” writes architect Nathan Williams whose work explores the African diaspora process. “Baraka is a space for simultaneous living and giving, creating and sharing,” he adds. All value the guidance Onnig provides and all claim to “learn from Kardash Onnig.” ”Onnig is a master . . . I consider him a mentor, despite all his resistance to such titles,” writes Gregory MacAvoy, a sculptor from Brooklyn, NY, in his musings “On the nature of collaboration.”

Three-Dimensional Vision

Onnig’s confidence in the possibility of making his vision of a three-dimensional world a reality is more rooted and anchored than ever. His has become a most appealing assertiveness which, rather than offend and turn off, reassures and inspires. The artist communicates his insights with an unusual calm. He also displays a “genuine and affectionate interest” in his interlocutor. Onnig listens mindfully, empathizes, and when possible, offers generous advice. Some of us may have witnessed the artist’s lashes and rages. These are never personal attacks, however. They are expressions of the frustration the artist feels over the fact that “the world looks away as blood is shed unjustly.” Commenting on one such explosion, where he was “the recipient of the scorn,” “Onnig is a serious man, worthy of his point of view,” notes MacAvoy.

A glance at the cover reveals that the book has a title but no author. “The following stories explore collaboration as an antidote to our egocentric mono-ism,” writes Onnig. Collaboration implies equal participation. Indeed, all of the artists, including the children the “whiskered toymaker” has great respect for, emerge as significant contributors to the seventy-three page volume. All items for Baraka’s Pushcart Derby, for example, which included a traveling portrait workshop, were collaboratively designed and hand-made. Paradoxically, however, the book which Onnig describes as “working toward the fulfillment of the desire to reach out to an other” has Onnig’s unmistakable signature stamped on it. The concept of Voki, the “experiencing of a transference: two others in collaboration,” (a concept I am yet to fully internalize) is Onnig’s. The spirit to include, to share and to give, give, give is Onnig’s. While others have died “giving,” to give, for Onnig, is life. More than with any of his numerous other projects, COLLABORATION is as much about the man behind the art as it is about the art itself.

Excitement is contagious and COLLABORATION has excitement written all over it. Indeed, the book is so entertaining that one loses sight of the seriousness and the urgency of the artist’s appeal to “redream this world.” The reader is equally oblivious of the ambition and the hard work that went into realizing the project. COLLABORATION is a labor of love, but it is also hard labor. Bringing the collaborators together to create an impeccably put together whole is a feat in itself.

COLLABORATION is a great finale, both in terms of summing up a decades-long career and also of leaving with a bang! Fortunately however, as always with Onnig, the exit is also a new entrance.

Main Photo Caption: Whimsical toys by Kardash Onnig