Program director of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights studies minor, Prof. Nancy Harrowitz, welcomed the virtual audience which tuned into Bilal’s lecture, entitled “Voicing and Silencing the Memory of Loss: Lullabies and Stories from Armenian Women in Istanbul.” Dr. Sultan Doughan, a fellow scholar, introduced Bilal, an historical anthropologist who uses ethnomusicology as her lens. Bilal’s lecture “illustrated the capacity of lullabies sung by Armenian women in Istanbul to produce knowledge, functioning as a survival strategy under the regime of denial following the 1915 Armenian Genocide.”

Bilal discussed her interactions with three women in Istanbul, all children of Genocide survivors. In her research, she stresses the connection between generations of women and how daughters of female Genocide survivors inherit their legacy through various ways, one of which is through information coded into music, song, and lullabies. Therefore, she focuses on working with women who are children of Genocide survivors, learning their stories and in particular how they learned about the trauma of the period from their mothers. One of those ways is how a mother sings lullabies to her children.

Read also

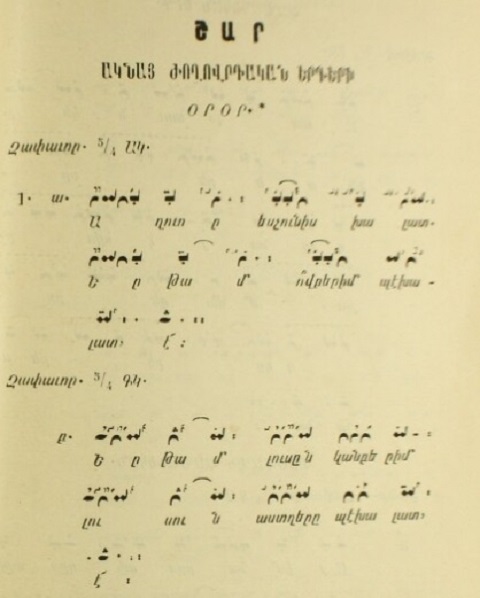

Bilal described meeting a woman named Naze who was born in Sasun to a family of survivors who managed to stay on their native land. Naze stressed that Sasun was historically Armenian territory referring to it as “Sasun Kavar, Hin Hayastan” (Province of Sasun, Ancient Armenia). Naze sang a lullaby she had learned from her mother Ruri, ruri, nsdim hed orrotsin. This was a folk lullaby from the region that Bilal had not heard before, in fact, probably very few people knew such songs. Modern Armenian lullabies such as Kun Yeghir Balas, Ari Im Sokhag and others produced by nationalist male poets and composers have taken up much of the floor in the years since the Genocide. Bilal was fascinated by Naze’s singing. She argues that music and songs perpetuate communal experiences; in Naze’s case, the life of Armenians in Sasun and of course the massacres that took place there.

In 1923 the Treaty of Lausanne effectively recognized the modern Republic of Turkey by the Western Powers. In the treaty three official minorities of the country were noted: Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. All three have been suppressed to varying degrees. The Suryani or Assyrians, i.e. Aramaic-speaking Christians, are another minority group in the country. They do not have an official status, but have also suffered suppression by the authorities. As for Armenians after the Genocide, they were caught between a desire to give voice to their memories and remain silent in order to avoid repercussions.

As Bilal states “The affective [i.e. emotional] knowledge of Armenians in Turkey stands at the core of what we can conceptualize as ‘double consciousness.’”

This of course includes the trauma of the Genocide passed down as emotions, feelings that mothers relay to their daughters, oftentimes without giving precise details.

The second woman Bilal spoke about in her lecture was Yerchanig. Yerchanig’s mother was a survivor from Kurtbelen. Because she survived the chart (massacre), Yerchanig refers to her mother as a “Chart-Digin” (Massacre Woman). Yerchanig’s mother, unlike some others, described many of the events that took place in 1915 and afterwards. She told her daughter that on the Monday after Vartavar she was deported from Kurtbelen with other women. She lost all her loved ones and wanted to kill herself. Apparently Yerchanig’s mother arrived in the Arabic provinces of the Empire (probably present day Syria) because she stated that she served an Arab family. Yerchanig’s mother said that others were sent to Der Zor and that “there was chart everywhere in Anatolia.” Eventually Yerchanig’s mother came to Istanbul where she met the man she was to marry. He tentatively asked her “about proposals.” Yerchanig’s mother said the Arabs had made proposals but she had refused. However, there is no way to know what really happened, as survivor women often kept silent about sexual violence. Yerchanig stated, “my mother was one history.”

The third woman discussed was Hripsime, born in Sivas in 1932. Her parents were from the village of Tavra, outside Sivas. Growing up, Hripsime heard from her elders that many of the people of Tavra were spared because they were millers who could supply bread to the Ottoman Army. Hripsime remembered the churches that were still standing in Sivas when she was growing up. A family member was claiming that the Turkish government was going to let the Armenians open the church up again. Hripsime’s father scorned this theory, saying “Do you really think that they will ever give it back?” Of course, they did not. The next morning the family woke up to find the church destroyed. Hripsime had a close relationship with her father who showed her various Armenian historical locations. One of the monasteries outside of Sivas was in a militarized zone. Hripsime’s father pointed out a building through the wire fence and told her it was the sanctuary of that monastery.

Hripsime, like the others, learned many songs from her mother and grandmother and wanted to transmit them. Bilal played a recording of her voice, which was probably the most moving part of the entire lecture. Hripsime sang in Turkish:

Sleep my little one, let me sing you a lullaby

Do not depress my sorrowful heart

You are left to me by the one who is gone

Sleep my little one, let me sing you a lullaby

Bilal found it too painful to continue and changed to a lullaby in the Armenian language dealing with motherly love.

Armenians that were left in Anatolia turned their ruined churches into sacred sites. They would visit these sites and naturally without having to say much it was understood that these used to be Armenian churches and clearly horrible destruction and violence had taken place for them to be ruined and few Armenians to be left; in other words, merely taking children to these sites implanted the reality of the Genocide in their minds. Meanwhile, the Armenians born in Istanbul forbade their children to travel to their native lands in the interior as they were still considered dangerous.

Bilal explained she aims to challenge the conventional concept of a “minority” group. As seen in her research, the stories and songs of the women all mark Istanbul as both “home” and a “place of displacement.” There is both loss and survival, and survival with tremendous losses. The songs accumulate and shape a memory, in everyday conversations or interviews to resist forgetting. These songs establish bridges between generations whose very existence is under the surveillance of the state. With such surveillance it is almost as if these women are talking in code. Common phrases in Turkish folk songs such as “I cried day and night,” and “I am burning now,” take on a different meaning spoken by an Armenian grandmother. As Bilal says, the memory of the Genocide is very much alive and inflicting pain up to the present.

After Bilal’s lecture was finished, a Q&A session produced a number of interesting points. Prof. Roberta Micallef from BU’s Department of World Languages and Literature served as moderator/respondent

One point Bilal touched on in the discussion was that an important part of her work is unearthing women’s voices. She is studying music memory through her oral interviews of women, and the history of the Armenian feminist movement through the written word. Bilal wishes to bring together the written and the oral arguing that they are not mutually exclusive.

The discourse on the Genocide has centered around war and Ottoman and Armenian politics and women and their stories have been sidelined, she said. Bilal noted that starting in 1879, Armenian feminists founded 50 girls’ schools in what is now Eastern and Southeastern Turkey. Some of her subjects were born in the towns where these schools once existed; thus their survivor mothers may have attended these schools. Moreover, Bilal thinks about the possibilities and the losses the Genocide entailed; while the conventional story is the loss of churches, male clergy, and male poets and political leaders, Bilal stresses that had the Genocide not happened, the women she interviews could have gone to these girls’ schools and possibly become writers, teachers, and so on.

Bilal’s view of the generation she interviews is that they are active gatekeepers of the unwritten culture, but also that they took up the baton from their feminist “older sisters” (or aunts) whose work was destroyed in 1915. Bilal points out that not only is the Genocide the history of the Armenian community but an enormous loss for feminists in general, stressing that the history of women in Turkey cannot be written without working through this past.

The research is emotional for Bilal at times because she is dealing with the elder women of her own community. “Sometimes it makes me hopeless about the future, but sometimes they empower me,” she said of her subjects. She added that “Some talk about the Genocide experience but some don’t, but even when they don’t, the language and dialect reminds that there was a community there, a language there that is lost today.”

Finally, Bilal added that in her work she deconstructs the genre identification of “lullaby.” She disagrees with the traditional understanding of lullabies, which according to her comes from a patriarchal point of view. Rather than being an impediment to objectivity, Bilal views being a “native ethnographer” (i.e. an anthropologist studying the group from which she came), as important. It gives her methodological openings that would be closed to others and helps her bring in the native voice. Bilal disagrees with many of the approaches traditionally taken in anthropology. She believes in methodology that aims to “decolonize.” 19th century ethnographers, who were mostly men, identified lullabies as simple songs that mothers sing to their children. This understanding denigrates women’s cultural and musical creations as simple and frivolous, and downplays their importance in transmission of history and culture. Bilal states that the lullabies she has studied are a repertoire of culture and musical memory. They can be political as well. How? Armenian lullabies are almost inherently political because they are singing in the Armenian language, which is discouraged by the Turkish state, and they were brought from a destroyed homeland (like Naze’s Sasun lullaby in the first example). In addition there are lullabies that directly or more often indirectly reference the Genocide.

The Boston University series continues through April 14.

Main Photo Caption: Prof. Melissa Bilal