On March 8, the Indian Ambassador to Iran Gaddam Dharmendra announced that India is planning on connecting the Chabahar port (a seaport in southeast Iran, heavily invested in by India) and the Indian Ocean with Eurasia and Helsinki through the territory of Armenia, creating an International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), adding that New Delhi is planning to make Chabahar the most important and busiest port in the region. This announcement spread enthusiasm in the Armenian press and some government circles. On this occasion, Deputy Prime Minister Dikran Avinian met with the Indian ambassador of Armenia on March 16 and discussed ways to boost trade between the countries and Armenia’s role in the north-south trade corridor. However, until now Armenia has been far from playing an active role in this project. The government lacks a clear strategy and its infrastructure requires huge foreign investments which are conditioned with the political stability in the country. This article will analyze the main geopolitical and economic goals behind India’s regional ambition and whether Armenia can fit within New Delhi’s Eurasian vision.

What is the INSTC project, and why it is vital for India?

The INSTC project was originally decided between India, Iran and Russia in 2000 in St. Petersburg and subsequently included 10 other countries: Azerbaijan, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine, Belarus, Oman, Syria and Bulgaria as an observer. It envisions a 7,200-km-long multi-mode network of ship, rail and road routes for transporting cargo aimed at reducing the carriage cost between India and Russia by about 30-percent and bringing down the transit time from 40 days by more than half.

The objective of the corridor is to increase trade connectivity between major cities of the member states. The primary goal of the project is to reduce costs in terms of time and money and increase trade volumes between member states. A study conducted by the ‘Federation of Freight Forwarders’ Associations in India (FFFAI) found the route is, “30 percent cheaper and 40 percent shorter than the current traditional route.” It is estimated that the corridor will facilitate carrying 20 to 30 million tonnes of goods per year. INSTC will help India gain smooth access into Central Asia via Iran and beyond.

Read also

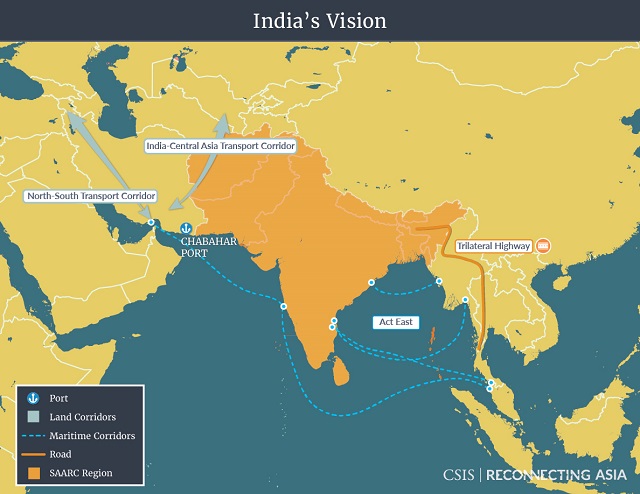

Geopolitically and geo-economically, the INSTC is also being seen as New Delhi’s counterweight strategy to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China is India’s competitor in the region. The corridor is going to leave a deep impact on India’s engagement with Eurasia, as India—the fifth-largest economy in the world—looks forward to fostering deeper and stronger ties in the region. INSTC also serves another one of India’s geopolitical interests as it bypasses archrival Pakistan and strengthens its cooperation with Russia and other members of the project.

Iran plays an important role as a transit hub in this project. To connect Eurasia to the Indian Ocean, India agreed to invest up to $635 million to develop the Iranian deep-sea port of Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman which is only 300 kilometers from Gwadar, the major Pakistani trade hub port heavily invested in by China. Predicting that Chabahar will change the regional economic dynamics, Iran’s Minister of Roads and Urban Development Mohammed Eslami called for assistance from India in developing the project. New Delhi successfully convinced the US not to impose any sanctions on Indian investment in Chabahar. To facilitate trade between India and Iran, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed in 2015 for the construction of the Chabahar-Zahedan railway project. The railway project is being said to align with New Delhi’s interest in creating an alternate trade route to Afghanistan and Central Asia bypassing the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Viewed from New Delhi, if implemented this would have been a strategic victory over China, which has been interested in having a major stake in the infrastructure sector of Iran.

According to Mher Sahakyan, founder and director of the China-Eurasia Council for Political and Strategic Research, INSTC is also full of challenges. The project might create an uneasy situation in which Iran might have to make a strategic choice between India’s INSTC and China’s BRI. Russia’s position is not so easy either. The INSTC and Russian interests converge as Russia would be connected to the Persian Gulf through railroads. However, Moscow faces Western sanctions due to its military and political involvement in Ukraine, making it harder for Moscow to make major investments in infrastructure projects in other INSTC member states. Furthermore, Russia is also participating in China’s BRI through the New Eurasian Land Bridge and the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor. However, according to Mher Sahakyan, Moscow doesn’t want to be a junior partner with Beijing, and for this reason it values INSTC and Russo-Indian cooperation, as Russia sees India as a partner for balancing power with the Asian superpower, China. In this context, the INSTC could become an important economic and strategic tool connecting Russia with the Gulf region and the Indian Ocean. Within this context, viewed from Moscow, the unblocking of trade routes between Armenia and Azerbaijan would further facilitate the project.

Viewed from Yerevan, an intersection point between Russian, Chinese, and Indian interests in the South Caucasus, Armenia needs foreign direct investments to revive and build its poor infrastructure connecting South Armenia to Iran through railroads. The next section will analyze why Armenia is far behind Azerbaijan in playing a crucial transit role and what steps must be taken to revive Armenia’s historic role along the Eurasian trade routes.

Armenia’s proposal: a strategy or a “pipe dream”?

According to the November 9 trilateral agreement, transport routes between Armenia and Azerbaijan should have been unblocked. However, this does not mean Armenia will join regional infrastructure projects as its infrastructures remain underdeveloped and in need of renovation and updates. If Armenia joins the project and INSTC passes through its territories, then it would have passages to both the Black Sea and the Persian Gulf. This would make it easier for Armenian shippers to enter international markets and export their products through simplified procedures over both land and sea.

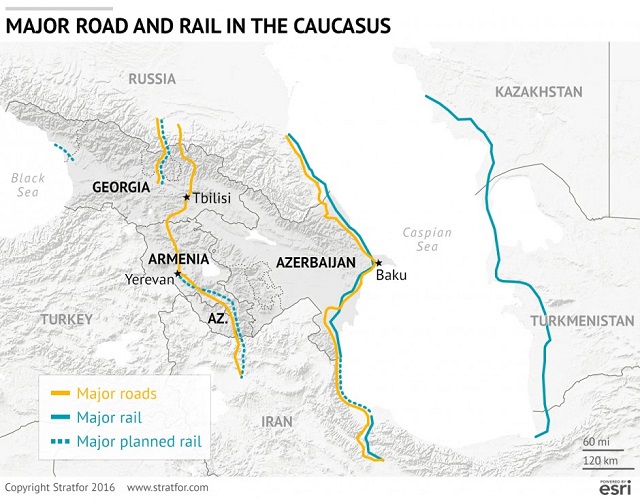

Armenia’s vision of the North-South corridor (roads and railways) connecting Northern Armenia to the South and Iran. (Source: Stratfor, January 2, 2016)

For this purpose, Armenia aimed to construct the “North-South” transport road, 550-km long, to facilitate communication with Iran and Georgia and beyond. Part of the construction roads are being implemented by the Chinese company Sinohydro Corporation (under the 2009 loan agreement with the Asian Development Bank). The construction work was to be completed in 2016, however, it began with a delay of three years. According to this agreement, Armenia received $40 million. The second tranche amounted to $50 million; negotiations are underway to provide the third tranche.

While, in the south, Armenia has proposed construction of the Armenia–Iran Railway Concession, also called Southern Armenia Railway. The project remains ink on paper with no financier as the economic feasibility is doubtful, though Armenia continues to try to find sponsors and private investors to make the project economically more viable. Before the feasibility study was completed by Dubai-based Rasia FZE investment company, the Southern Armenia Railway was anticipated to be a 316 kilometer railway linking Gavar, 50 kilometers east of Yerevan near Lake Sevan, with the Iranian border near Meghri. Following a meeting on September 3, 2013 with former Armenian President Serge Sarkissian, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that Russian Railways could invest about RUB 15 billion in the development of the Armenian Railway. The feasibility study results indicated that the Southern Armenia Railway would cost approximately $3.5 billion US to construct; the lengths were reduced to around 305 kilometers from Gagarin to Agarak, providing a base operating capacity of 25 million tons per annum. The railway will have 84 bridges spanning 19.6 kilometers and 60 tunnels of 102.3 kilometers, comprising 40-percent of the total project length. As the key missing link in the International North-South Transport Corridor, the Southern Armenia Railway would create the shortest transportation route from the ports of the Black Sea to the ports of the Persian Gulf.

According to the study, Southern Armenia Railway would establish a major commodities transit corridor between Europe and the Persian Gulf region, based on traffic volume forecasts of 18.3 million tons per annum. Moreover, the Armenian-Iranian branch of the railway will connect with the longer branch Tabriz-Tehran-Gorgan (Iran) – Etrek-Bereket-Gyzylgaya (Turkmenistan) – Zhanaozen-Aktau-Nur-Sultan-Dostyk (Kazakhstan) – Urumqi (China). This railway is of strategic importance because it will connect Armenia as a member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) not only to other member states but also Iran, India and China.

However, this may turn into a “pipe dream” since Armenia’s main regional partner Iran seems reluctant to provide a loan for the construction of the Armenian part of the railway – which is approximately 250 kilometers. The Iranian part of the railway is around 60 kilometers. Besides, it is notable that Armenia’s state railway company is largely owned by the Russian “Southern-Caucasus Railway” company. That is, all developments are dependent on Russia’s political will and developments in Armenia.

According to Mher Sahakyan, the implementation of the North-South road corridor has a geopolitical advantage as it will also increase the security of Armenia. It is worth mentioning that one of the main important factors to winning a war is to facilitate the fast movement of military units and equipment and supply routes. In this context, Sahakyan argues that the North-South road will strengthen Armenia’s security and the combat readiness of the Armenian army. However, Armenia is far from implementing this project in the short term, as Azerbaijan has emerged as a strong competitor and trustworthy partner in the project.

Existing railways and transit roads of INSTC connecting major Eurasian cities to each other. (Source with permission: CSIS Reconnecting Asia, Insights on India, May 3, 2021)

Azerbaijan’s advantageous position

Unlike Armenia, Azerbaijan is heavily involved in the project, building new train lines and roads to complete missing links in the INSTC.

Founder and director of the “Armenia – Iran strategic cooperations development center” foundation Pooya Hosseini argued in an interview that Azerbaijan is creating every condition and making every effort to have the corridor pass through its territories, thereby increasing its role in international and regional processes while keeping Armenia under further economic blockade and isolation.

In 2005, Azerbaijan’s accession to the INSTC agreement paved the way for connecting India to Russia via Iran and later Azerbaijan by linking the Iranian railroads to the West of the Caspian Sea. This railroad has another positive factor that can link India to Europe via Turkey by connecting the Iranian-Azerbaijani railroads to the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railroad. Anticipating cargo transit through its territory in the range of 15 to 20 million tons at full capacity, Baku has been especially active in upgrading infrastructure and building new roads and railways by attracting foreign and local investments. In 2019, Azerbaijan planned to invest $1 billion in its railway infrastructure by 2022.

Azerbaijan also has another advantage: a new railroad that has been constructed in Iran covering a 164-kilometer span between Rasht and Astara via Anzali, Iran’s other major Caspian port city. The line is also supposed to enable travel between Baku and Nakhichevan. For this reason, Azerbaijan has agreed to jointly finance the project, with each side contributing $500 million. According to a Center for Strategic and International Studies report, Baku has also provided a $1.5 billion soft loan to Iran for the construction, which started in the first half of 2018 and will run through 2022. Iran has started construction work to complete the missing link of the Qazvin-Rasht-Astara road and railway (205 kilometers) including the Rasht-Astara section (164 kilometers). The project involves the construction of 369 kilometers of bridges and railway lines to link the southern sections to the northern ones.

Azerbaijan, despite being India’s archrival Pakistan’s strategic partner, with its advanced railroad systems is playing a greater role in implementing India’s Eurasian vision in the INSTC than Armenia, which is in dire need of investments to revive its role in these trade networks.

Conclusion

According to Hosseini, Armenians must take into account the geopolitical factors too. Political and geopolitical interests are shifting; new developments are occurring in the region and such developments would have an impact on international trade. Recently, the Pakistan-Azerbaijan-Turkey axis has pushed India to increase its interest in Armenia and would like to see the INSTC passing through the Armenian territories, keeping in mind that Armenia is also the only country in the EEU that has a land border with Iran. Taking into account Iran’s desire to become a full member of the EEU in the future, as well as India’s interest in the EEU structure and possible future membership, Armenia’s chances of joining regional trade projects would be high.

Meanwhile, in addition to the geopolitical component, Armenia will be able to be involved in the transport corridor if it successfully finishes the construction of its North-South road corridor. The building of the North-South Corridor will provide Armenia with an opportunity to strengthen its economy, security and geopolitical position. However, given Azerbaijan’s advantage concerning its infrastructures, Armenia must engage in India and seek trade partners and investors to invest in the North-South corridor which is very costly for the Armenian government. Hosseini argued that Armenia can attract investments from India only through three decisive factors: strengthening political relations with New Delhi, increasing its economic activities and engaging lobbying efforts. Thus, the Armenian side should organize business forums and invite Russian, Iranian and Indian entrepreneurs and investors for this purpose. If Armenia uses these three factors proportionally, the chances of being part of such important international projects increase.

By joining such projects, Armenia would not only be freed of trade isolation imposed by Turkey and Azerbaijan, irrespective of the unblocking of trade routes between Yerevan and Baku according to the November 9 trilateral statement, but also become a crucial player in international trade routes and attract the interest of rising regional powers. This project should be a top national security priority for Armenia as it must take serious measures to end its isolation and attract foreign investments in the road and railway projects. If Armenia does not develop a coherent strategy, then its projects would turn into no more than a “pipe dream.”

Yeghia Tashjian

Main Photo Caption: The International North-South Transport Corridor route via India, Iran, Azerbaijan/or/and Armenia (if possible) and Russia. (Source with permission: CSIS Reconnecting Asia, Competing Visions)