LONDON – Recently, the Turkish newspaper Daily Sabah published an article in which it calls Turkey a “land of diversity” thanks to the six featured churches that have been “protected” by the Turkish Ministry of Culture (see “Land of Diversity: 6 Most Beautiful Christian Sites in Turkey,” by Argun Konuk, Daily Sabah, April 2, 2021). While everyone is grateful whenever cultural heritage is preserved and protected by a state, the Daily Sabah article tells a small part of the story of the thousands of churches – Byzantine, Armenian, Greek, Georgian, Syriac – that have existed in Anatolia (Western Armenia), often times for centuries, and their fates under the modern Republic of Turkey, established in 1923.

This brief response addresses the histories of only a handful of Armenian churches in the Republic of Turkey with the goals of: encouraging the press (both in Turkey and beyond) to do a better job of covering these topics; drawing attention to the long-term, intentional erasure of Armenian history in the Republic of Turkey; helping individuals (in Turkey and beyond) to see the destruction and neglect of Armenian cultural heritage as part of a serious problem related to the creation of nationalist narratives in Turkey that exclude the existence of indigenous Christian populations, thereby depriving individuals living in Turkey of truly knowing the histories of the lands in which they live and, thus, of their own cultural inheritance.

Most of the properties formerly belonging to Armenians were confiscated by the Turkish government and turned into military posts, hospitals, schools and prisons in the aftermath of WWI and the Armenian Genocide. The legal justification for the seizures was the law of Emval-i Metruke (Law of Abandoned Properties), which legalized the confiscation of Armenian property if the owner did not return. Still, some individuals (including some Turkish citizens) believe that the Treaty of Lausanne stipulates that the government of the Republic of Turkey preserve the heritage of its minority populations.

In a 1974 report, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) estimated that after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, 913 Armenian historical monuments were still in existence in Turkey, with 464 completely destroyed or vanished, 252 in ruins, and 197 in need of immediate repair. UNESCO recently researched and authored a report uniquely on the heritage of Ani and its environs in 2015. In 2016, the archaeological site of Ani was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Read also

Thanks to the interventions of UNESCO, the World Monuments Fund and the Turkish Ministry of Culture, recently some important preservation work has been completed on Armenian monuments in and around Ani (See https://www.wmf.org/publication/ani-context-workshop). We see these efforts as a step in the right direction, but they are not enough. There is much work to be done. Much history to be remembered. And many sites of distinct artistic, cultural and religious significance to be shown the respect they deserve, as part of the fabric of humanity.

For more information on Armenian, Greek, Jewish and Syriac cultural heritage in Turkey, see this interactive map created by the Hrant Dink Foundation in Istanbul: https://turkiyekulturvarliklari.hrantdink.org/.

Bishop Hovakim Manukyan is Primate of the Armenian Churches of the United Kingdom and Ireland and Member of the Committee for the Religious and Cultural Heritage Protection of Artsakh of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, Armenia.

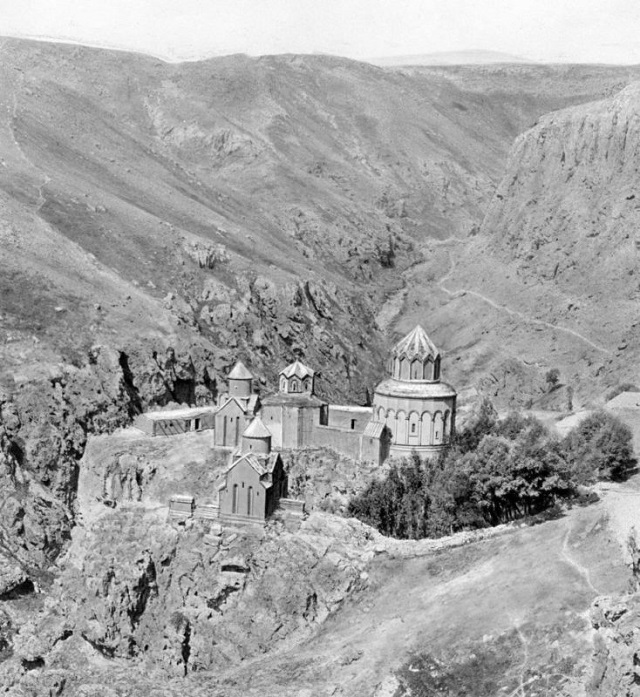

Khtzkonk (Beş Kilise), Kars

The remains of this complex, constructed between the 7th and 13th centuries, are located in the province of Kars, near Digor. Active as a site of pilgrimage until 1920 – when it was photographed by the archaeologist Ashkharbek Kalantar, the site was visited in 1959 by Jean-Michel Thierry who found that four of the five churches had been completely and intentionally destroyed. Only one of the five churches – that of Saint Sarkis – remains partially standing today. According to fieldwork done by Tessa Hofmann, locals reported that that the churches were blown up with explosives by the Turkish military. See: Tessa Hofmann, “Armenians in Turkey Today: a Critical Assessment of the Armenian Minority in the Turkish Republic,” p. 40.

Surp Azdouadzadzin, Arapgir

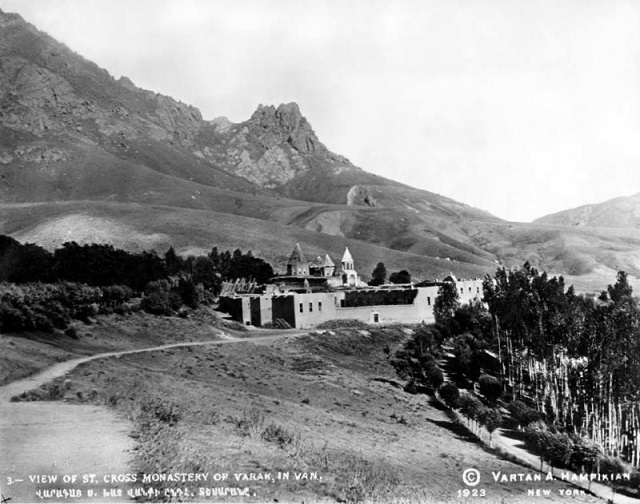

This monastic complex – of seven churches – was founded in the 11th century and was initially home to a piece of the True Cross, deposited there by Saint Hripsime, according to Armenian tradition. Destroyed (by earthquakes and invasions) several times throughout its long history, the monastery was consistently rebuilt as it was a site of religious and educational importance for the indigenous Armenian Christian population. Similar to the monastery of Msho Sultan Surp Karapet, Varakavank was looted during the Hamidian massacres of 1895 and, similarly, became a site of respite for individuals trying to avoid extermination during the Armenian Genocide of 1915. The site was intentionally destroyed in 1915, according to the account of Clara Ussher. While many remnants of the site existed til the 1960s, it seems there was a second attempt at destruction during that decade. The current remains consist of a small portion of the monastery – namely, parts of the church of Surp Gevorg (Saint George) and are owned by a private individual, namely Fatih Aytayli. It was reported in 2017 that many of the stones of the remnants were intentionally taken down to be used as spolia in the construction of a mosque and some houses. For more recent images, see: https://web.archive.org/web/20110727041753/http://armenia.loois.org/section.php?i=Turkey%2FVaragavank

Surp Nishan, Sivas

The village of Talas (in Kayseri) was home to two Armenian Churches, Surp Toros and Surp Asdouadzadzin. Surp Toros was built in the 17th century and was the only Armenian church in the village until the church of Surp Asdouadzadzin was built, in 1837. According to the work of Arshak Alboyajian (Arshak Alboyadjian, Patmut‘iwn Hay Gesario, Cairo, 1937) the churches were in function until 1915, but upon his return to Talas in 1937, he notes that they had been completely destroyed. Today, it is impossible to find any trace of either church in Talas. For more on the disappearance of Armenian architectural heritage in Kayseri and its environs, please see: Francesca Penoni, “Armenian Religious Architecture in Late 19th Early 20th-century Kayseri: Spatial and Cultural Cleansing,” Unpublished M.A. thesis (Sabanci University, 2015).

Taylar, Kars

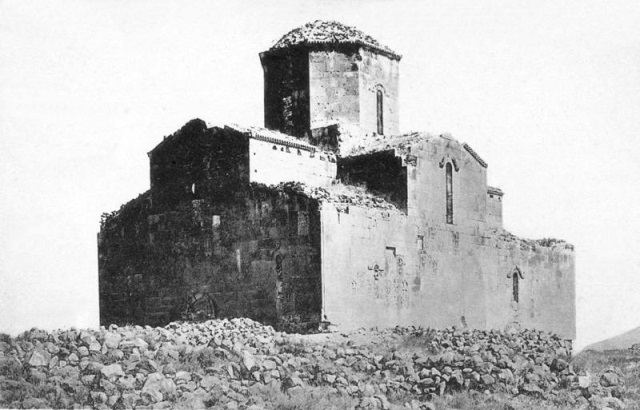

The plan of Taylar Church (likely constructed in the early 10th century) represents the Armenian “domed hall” on a smaller scale and in new proportions. Unlike mainstream examples, which depict the evolution of this architectural type in Bagratid times that show the eastern pair of pylons verged on the apse, the architect of Taylar reversed the traditional interpretation and situated the dome over the center of the naos. As a result, the dome’s position on the exterior is slightly displaced from the center of the main volume to the west. The structure is in a dangerous condition. There is serious damage on the southern and eastern support walls and the vault’s close-domed square is completely collapsed. The surfaces are marked with graffiti and the presence of small holes suggests that guns were fired at the walls. There are also indications that the site was previously used as an animal shelter. See: http://www.virtualani.org/taylar/index.htm

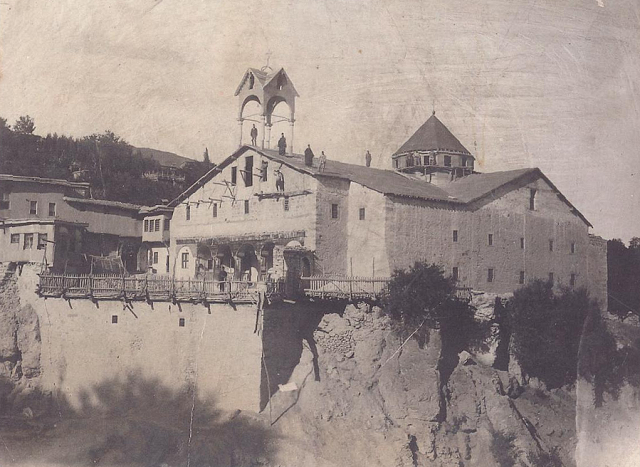

Bagnayr, Kars

Together with Argo Aritch, Karmirvank, and Horomos, Bagnayr was one of the ecclesiastic and cultural centers closest to Ani. It consisted of a large group of interrelated buildings and two separate churches. The main building of the complex is the large, domed hall of Surb Astvatsatsin Monastery, built between the tenth and eleventh centuries. One of the separate churches, Küçük Kozluca Church, also remains standing. Photographic evidence from the early twentieth century shows the large complex of monastic buildings intact but damaged. In the decades since the middle of the century, however, most of the structures have deteriorated and have been lost. Currently, only one of the original buildings, Küçük Kozluca Church, remains more or less preserved. This six-foil domed church has lost all of the coverings, and almost all of the exterior stone blocks have been scavenged, but the structure remains intact. At the primary building of the complex, Surp Asdouadzadzin Monastery, the eastern and northern walls remain along with two columns and the ceilings of the eastern nave of the zhamatun, allowing us to understand the original design. See: http://www.virtualani.org/bagnayr/index.htm

Mren, Kars

Constructed in 638 C.E., at the height of the Byzantine-Persian wars and the start of the Arab conquests, Mren is a touchstone of a world ravaged by conflict and the fruits of collaboration among diverse political constituents. Historians of Armenia, of the late Roman and Persian empires, and of early Islam have studied its inscriptions and sculptures for precious insight into this poorly documented era. At the same time, scholars value Mren as a canonical monument of the “Golden Age” of Armenian architecture, as the largest preserved domed basilica from seventh-century Armenia, and as an inspiration for the celebrated nearby Cathedral of Ani (a.d. 989). At the same time, Mren is cherished by Armenians internationally as part of their cultural heritage. Satellite images reveal that Mren is surrounded by an extensive archeological site. On the cathedral itself, there is graffiti and signs of illegal excavations. Mren was listed on the World Monuments Fund Watch List in 2014. For more information, see: https://www.wmf.org/project/cathedral-mren

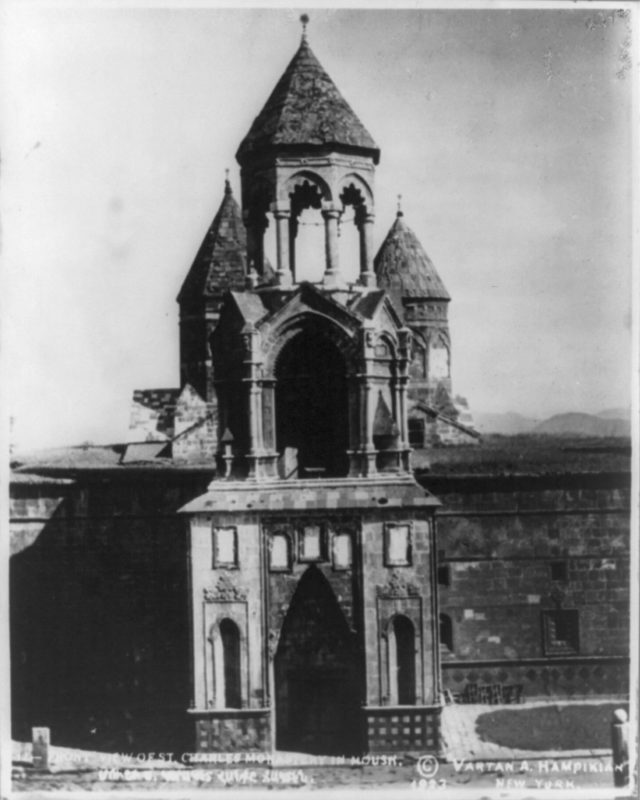

Karmirvank, Kars

Nothing is known about the origin of the church and the monastery, though the walls of the church have inscriptions that elucidate Ani’s history in the thirteenth century. The church’s plan exhibits the reduced variant of a “domed hall” type, with one western pair of under-dome pylons. It is inscribed in a very compact, roughly square, volume. A cylindrical drum stands over the arches and pendentives. Two pastophories with absidioles are located in the eastern corners and open into the naos. The west façade is highly articulated with moldings. Khachkars inserted in the western facade are typical for the last decades of the tenth century. Monastic buildings, and probably the refectory, were situated southwest of the church. The condition of the buildings has rapidly deteriorated in the recent past. As recently as the early twentieth century, the buildings were in considerably better condition than they are currently. Although the roof remains intact and the church is still standing, there is extensive damage, including serious destruction on the west and south façades, where the lower parts of these walls were completely destroyed. Of the monastic buildings located southwest of the church, only walls are partially preserved. http://virtualani.org/karmirvank/index.htm

Argina, Kars