By Dr. Arpi Sarafian

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

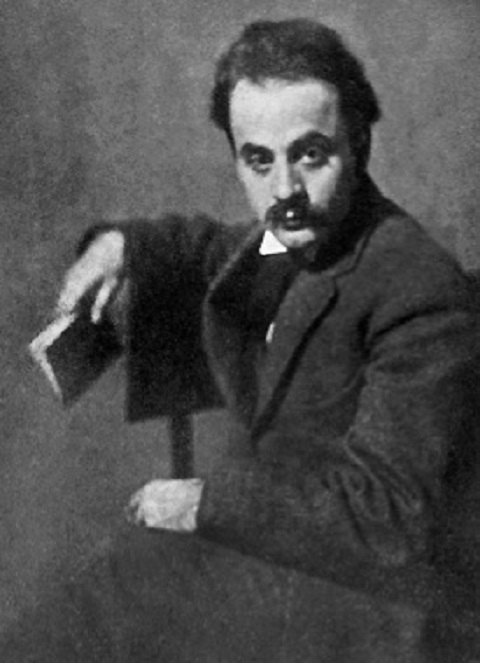

I was recently gifted a copy of the 1984 translation into Armenian (Technopresse Moderne, Beirut-Lebanon) by renowned poet Vahe-Vahian of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet. An article I had read earlier that week about another translation into Armenian of Gibran’s internationally acclaimed classic prompted me to take a close look at my newly acquired treasure. In his “Markaren,” [“The Prophet”] published in the February 10, 2021 issue of Nor Or weekly, Archbishop Hovnan Derderian refers to Very Reverend Father Pakrad Bourjekian’s 1999 translation into Armenian (St. James Press, Jerusalem) of The Prophet as “a gem . . . impossible to compare with other existing translations.” The archbishop’s comments are undoubtedly well-founded. Bourjekian’s translation must have its merits and deserves to have its rightful place in our literary canon. My intention here is not to compare the two texts. Instead, I wish to draw attention to the earlier translation as well, still waiting to be resurrected and known to those who cannot, or perhaps have no desire to, read the book in the English original.

Read also

Not too long ago, I had read Vahe-Vahian’s translations of Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore’s The Gardener, Gitanjali, and Fruit-gathering, works I was not familiar with at the time. I remember being captivated by the musicality and the lyricism of the Armenian translations of these classics. I could therefore not wait to read The Prophet, a book I had long ago adopted as “my little Bible,” in our mother tongue.

The Prophet has been a favorite of mine because of Gibran’s deep insights into the condition of man and of his infinite compassion for an ailing humanity. The protagonist, a visionary hermit living in the wilderness around the fictional port city of Orphalese, in a country away from his native land, shares his wisdom and knowledge with the town’s inhabitants, gathered to hear “of your truth,” before he sails back to his homeland after twelve years of exile. With “a bent head” and “tears falling upon his breast,” the “Prophet of God” speaks: “Forget not that I shall come back to you . . . the spirit of the earth shall not sleep peacefully upon the wind till the needs of the least of you are satisfied.” The “wanderer” beseeches his “brothers” to wait patiently for their reward in some other transcendent realm. (Is going to another place the point of life?) The notion of a “reward” affirms their pain: “Not without a wound in the spirit shall I leave this city.”