The Project

Guerguerian, born and raised in Paris, moved to Belgium four years ago. He worked for many years in the field of information technology before going to Indonesia in 2012 and opening a series of French bakery/cafes, for which he continues to work as sales and marketing manager. The 42-year-old also has been volunteering for various Armenian projects since the age of 19. Guerguerian prior to the 2020 war was working with Tufenkian on an agriculture project for the Kashatagh region of Artsakh, which of course had to be cancelled. Tufenkian and he then came up with the idea of finding the most adaptive solution for housing refugees from Artsakh.

Read also

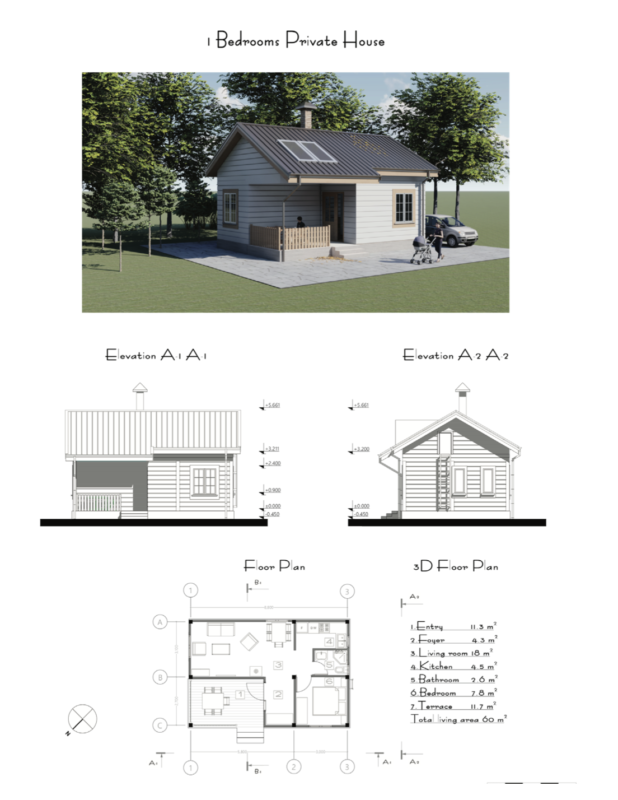

Guerguerian began collecting information but it turned out to be too technical for him, he said, so he reached out for help from Der Kevorkian and Asryan, who have extensive relevant knowledge. By the end of December 2020, the team was set up, and the members began to design six or seven options for housing construction, from cheap to more expensive, which could be built from the span of a few days to that of several months. After preparing a catalogue, they began presenting it to different organizations to do fundraising and start the project.

Der Kevorkian explained that the efforts to construct housing in Gyumri after the 1988 earthquake provided the group good lessons in potential problems to avoid. First and foremost, he pointed out, was to act quickly and not begin projects which might last forever, as it seemed happened in Gyumri. Secondly, container housing has a bad reputation now among Armenians because of what happened there. Although the technology for the construction of such housing has advanced and is better now, it will not be accepted.

Der Kevorkian said that they reoriented their research towards stable solutions. He said, “That is why we ended up choosing cement panels, which are very solid and at the same time very handy. We can build these houses very quickly. This approach is between two extreme solutions, one being the container panel housing, and the second, building something very solid, with basalt, stone and heavy materials.” The latter is the traditional Armenian approach to homes. However, using prefabricated cement panels both allows for solidity and relative speed of construction, he said.

The prefab concrete panel construction system can be used in four types of layouts, from one bedroom to four per house, and the aim is to deliver housing before the first of September.

Guerguerian interjected that they did not want to chose a solution without any knowledge of how the people in Artsakh actually lived. They saw other proposed designs, including one from Boston, which would have forced the local people to change their lives to adapt to it. Asryan as part of the team was able to provide the knowledge of local life. Their design was able consequently to take into consideration the needs of people. For example, the lack of roads means it is always muddy outside and having places to store dirty boots or shoes is important.

Der Kevorkian related, “We went and visited so many sites around Stepanakert, Martuni, and other parts of Artsakh. The idea was to find a way to integrate our project as much as possibly socially and architecturally in the existing landscape.”

Security is also considered in the urban planning design, Der Kevorkian noted, with a safe underground gathering site in case of complications a possible addition.

They also have been in close contact at each stage in the project with Artsakh government officials like the aforementioned Khanumyan and Chief of the Presidential Staff Artak Beglaryan. Guerguerian said, “We are not reinventing the wheel. We just are making sure that the design is adapted to the final users.”

Der Kevorkian summarized the value of their approach: rapidity, insulation which is a must in Artsakh where there are energy and water problems, and the initiation of new types of construction systems.

The Next Stage

Guerguerian stated that he and Der Kevorkian are operating as a company, with salaries and expenses. He said, “I don’t want people who work on this project to be volunteering. I think we need to switch to a more professional mode.” The company itself will be a nonprofit, however. Its mission is to build houses and give them to the Artsakh government. The government then will make arrangements with future tenants or owners. The first stage is to do a pilot demonstration project, hopefully to build 15 houses.

Artsakh Toun has been working with the Hayastan All-Armenian Fund (HAAF). Guerguerian said, “They are interested in our solution. They just need to see some proof.” A purely French organization called Oeuvre d’Orient, which helps Eastern Christian peoples, agreed to provide an initial grant to start work on a village and hopefully HAAF will order five more houses to add to this pilot project so it can be 20-25 houses, he continued.

If the Artsakh Toun approach is accepted, the first full-scale project will be to settle 107 families displaced from the Hadrut region villages of Mokhrenes, Taghot and Hakaku in a group of villages, including Dahrav, some 10 km. north of Stepanakert. Guerguerian said that the budget for this would be 3.5 million dollars just for the houses, not including other connected work that must be done.

Der Kevorkian said while it would be ideal to keep all families from specific villages as in the Hadrut area which are lost to Armenians together in new villages, it is very difficult to found a new village from scratch. It costs a lot because creating a new infrastructure, with roads and electricity and utilities is difficult, and will take a lot of time. The fear would be that money will run out before the new village is complete. Instead, he said, Artsakh Toun proposes adding a small number of new houses to existing villages, so that they can use the existing infrastructure, if necessary with some renovations and additions. The existing villages will be stabilized and made more viable.

The Artsakh government will decide which villages are suitable, and how many houses are needed, and Artsakh Toun will serve as the solution provider. Der Kevorkian said that discussions are ongoing with the government, with weekly online meetings to clarify this approach.

In the initial stages of the project, the construction materials must be imported, Der Kevorkian said, due to the need to quickly prepare housing before next winter, but local contractors in Artsakh and Armenia have been identified. Asryan, he said, had built perhaps thirty percent of Stepanakert, so his local connections are invaluable in this regard.

In the future, Guerguerian said, the ideal would be to set up a manufacturing plant in Armenia, perhaps with a branch in Artsakh, which could produce the necessary concrete panels, and maybe even export them eventually. This would bring potential foreign investment and boost the local economy while breaking dependence on outside manufacturers.

The structures designed by Der Kevorkian and Asryan are suitable for adding solar and thermal panels. Guerguerian said that the French Armenia Fund has experience in this kind of work so it may be possible that they come with a specific brigade to install such panels. He said that China produces them at reasonable prices and pointed out that Artsakh lost a lot of its electrical production capacity due to the war so solar energy is helpful.

Finances of Artsakh Toun will be kept transparent, Guerguerian said, with a CFO and accountant hired, and information communicated to all donors and published.

The Future

In the long-term, Guerguerian said, after housing is provided, and then energy, the next stage will be to provide the residents with a way to earn a living. Guerguerian was optimistic for the future, declaring: “There is a strong mobilization taking place. I can feel it. At the moment, in post-war Artsakh, there are a lot of experts that are joining in to help solve problems.”

Guerguerian pointed out that ultimately, the choice of what approach to take concerning housing is in the hands of the Hayastan All-Armenian Fund (Himnadram), because it has an estimated budget of some 200 million dollars collected during the recent war. The governments of Armenia and Artsakh have limited resources and other outside organizations at the most can probably donate several hundreds of thousands of dollars, while the scope of the housing need is much greater. Consequently, it is HAAF which must to choose the best solution and do the coordination.

There are other competitors to Artsakh Toun, Guerguerian admitted, such as a group doing cheap wooden houses, but he felt they were not resistant.

Guerguerian said that HAAF has a great deal of experience in construction, with a manager working in this field for 17 years. Its traditional approach in building is fine, he said, but slow. HAAF is a large organization and its decision-making process is also slow.

Guerguerian said, “I have been asking them for three months now. It is taking too long…If we wait too long, the refugees in the best scenario will move to Armenia. In the worst scenario, they will leave the country.” His hope is that HAAF will take action soon.

In the meanwhile, he and Der Kevorkian want people to learn about their project and attract experts such as engineers and architects to join their efforts. If people also want to donate, they can send money to the Armenia Fund or HAAF, and type in Artsakh Toun as the desired destination.

For more information, see the Tekeyan Cultural Association video interview with Kevorkian and Guerguerian conducted by Arto Manoukian at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNvQRoNNWgc&feature=youtu.be.

Main Photo Caption: Movses Der Kevorkian