Recently, I was talking to a friend who teaches overseas, and they told me an interesting fact. It seems that in leading Western universities, even if a student is going to get a degree in science, business, or, say, IT, 25 percent of their credits must be within the humanitarian studies, which is called liberal sciences there. Of course, here, just as with other classes, there is an opportunity to decide. A student can choose language, literature, history, philosophy, and so on, but they will not get their degree without getting credits in those subjects (By the way, the people changing our education system should also consider that fact).

There are at least two reasons for this. First, if you are going to become a nuclear physicist, genetic biologist, or an artificial intelligence IT professional, the ethical component of your science, your work, especially in the 21st century, comes to the foreground. Second, in order to advance in the same science, a critical approach is needed; that is, you must not accept any assertion of any theory “instead of melted butter.” You must combine it with other assertions and theories, after which you will come to your intermediate (but never final) conclusion. And what will be useful to you in that instance if not your humanitarian knowledge?

Yes, but the humanities are not being taught in schools and universities as they have been in Armenia for at least the last 50 years. In other words, if you write a few lavish sentences about the “bitter fate of the long-suffering Armenian people” while writing an essay on history or literature, you will definitely not receive a positive grade in a quality American high school. You need to substantiate what you say by gathering many, often contradictory, facts. In other words, literature or history is not “about talking,” as we have thought for decades. The humanities (and, consequently, the way it is taught) require the same “strict” approaches as the non-humanities. And most importantly, it requires critical thinking that has not been brought up in us, and we have not been able to inject it into those who come after us.

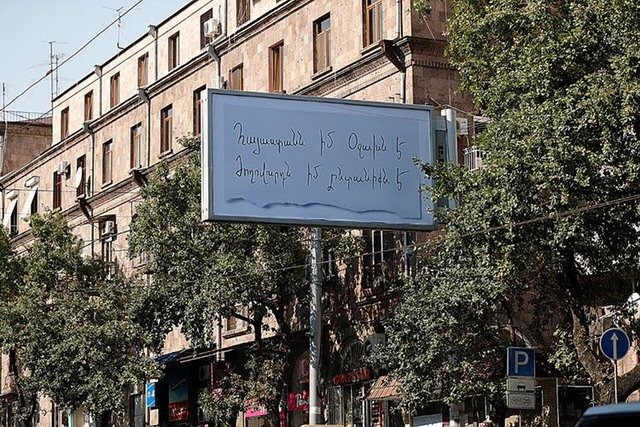

Are these wrong, archaic, and pretend patriotic approaches one of the reasons why our citizens, even if they know the patriotic lines of Hovhannes Shiraz or Paruyr Sevak (who once played a huge positive role), do not feel pain for the lost homeland? Or, when the head of the country, in fact, says that the people are his family and he is their “father,” and that “saying,” gaining the status of an official slogan, becomes a poster, it does not cause any internal resistance in society.

Read also

Aram Abrahamyan