The Armenian Mirror-Spectator

by Edmond Y. Azadian

I spent the entire month of June in Armenia. Back home, when friends ask me how I found Armenia, I cannot help but make an analogy by saying, “People are at the last dance on the Titanic.”

Read also

Before arriving there, I anticipated seeing gloom and doom all around, with some of the 5,000 losses not even buried yet, the other 10,0000 injured pinning their hopes on prostheses, and everyone listening to the news about daily incursions of Azerbaijani forces across Armenia’s borders.

However, the contrast was so bewildering that I could not come up with a rational explanation. Either people have become so fatalistic that nothing that happens scares them anymore, or they are so resilient that they are facing adversities with courage and hope. A third possibility is that they know something that we outsiders don’t, but it may also be any combination of the above.

Armenia’s political life, particularly within the parliament, reflects the very same divide, pitting domestic political unrest versus the reality right outside the country’s borders.

Polarization runs deep; objectivity has lost its meaning and relevance in Armenia’s political world. That polarization is also reflected when it comes to views of the diaspora. For example, you cannot congratulate Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan on his reelection, wishing him and his team well in governing Armenia, and then dare to criticize him if he blunders in a foreign policy matter. If you are with him, or his opponent, Robert Kocharyan, you have to believe that your hero is infallible; in fact, politics have been transformed into a religion and anyone outside your faith is considered a heathen.

One may wonder how a country so divided can stand together and survive.

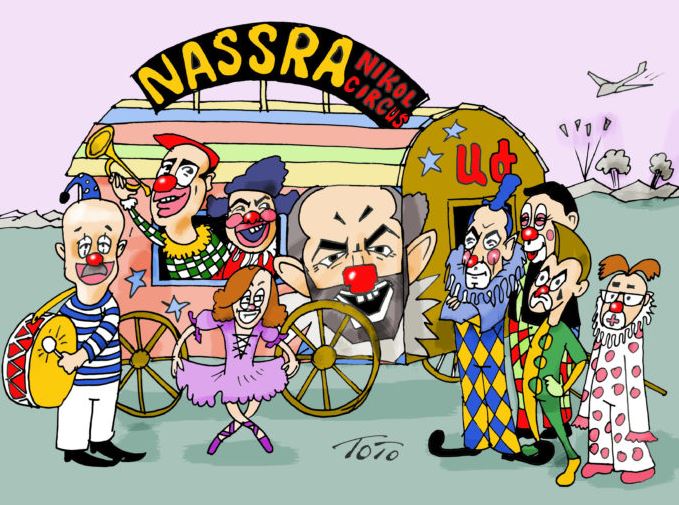

The charade that took place in Armenia’s parliament last week illustrates this division colorfully. August 2 was the date when the eighth session of the parliament was opened to elect the speaker and his deputies, along with the leaders of the parliament standing committees.

The opposition had come to the parliament to disrupt its normal functioning and one of its leaders, Ishkhan Saghatelyan, who later became the opposition candidate for the position of deputy speaker, did not hide that intention and announced that the struggle would continue until the ruling party was defeated.

Then the parliament became the scene for a show where the opposition members were wearing t-shirts with the pictures of their fellow elected members emblazoned on them, because the latter had been incarcerated on charges of violating election laws. After kindergarten-style enthusiastic clapping, the opposition members left the parliament in a showy manner; someone unfamiliar with the country’s situation could not have guessed that this was the legislative chamber of a country in trouble.

The election results handed 71 seats out of 107 to Pashinyan’s Civil Contract party, 29 to Kocharyan’s Hayastan alliance and 7 seats to Serzh Sargsyan’s Pativ Unem [I Have Honor] alliance, headed by former security chief Artur Vanetsyan.

The constitution mandates that one of the deputy speakers represent the opposition. The selection of that deputy also further fueled the carnival atmosphere with the participation of war hero and former minister of defense, Seyran Ohanyan, who has proved to be one of the country’s most sophisticated military leaders.

Following the elections, Kocharyan dropped his mandate, decapitating the opposition. The majority of opposition votes were cast for Kocharyan, who is rumored to have invested large sums in his election campaign. But with Kocharyan absent from the scene, the baton was passed to Saghatelyan, the organizer of the 17-party opposition movement headed by former Premier Vazgen Manukyan, which fizzled within a few weeks.

Saghatelyan also represented the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), which, though it has one of the best-organized political machines, never crossed the 1.5-percent bar in the elections.

In a way, Kocharyan ceded his position to Saghatelyan, bypassing Seyran Ohanyan, who became the head of the opposition faction. Many who had voted for Kocharyan did not intend to support Saghatelyan or his party.

This worked out well for Pashinyan too, as the ruling party was not displeased to see a streetwise candidate who lacked political finesse be elected as deputy speaker from the opposition. The behavior and actions of the opposition were embarrassing, to say the least.

But turning the tables, the ruling party has to share the blame for having provided an excuse for the opposition’s conduct.

Following the elections, Pashinyan’s ruling party had promised to use the iron fist of the law, which many voters welcomed. We had warned that if that decision was applied universally, it would help the country to recover at least internally but if that fist was used selectively, which had been a hallmark of former regimes, then it would lead the country toward disaster. Unfortunately, the latter was practiced, causing turmoil.

Two candidates who were running on the opposition slate and were duly elected did not show up in the parliament because they were in jail, accused of violating election rules. Those were Mekhitar Zakaryan and Artur Sargsyan. Two other mayors were also incarcerated for the same charges.

Earlier, Dr. Armen Charchyan was detained for the same reason. Incidentally, Dr. Charchyan runs a hospital owned and operated by Holy Echmiadzin, with whose leader, Catholicos of All Armenians Karekin II, Pashinyan and his teammates have an ax to grind.

All these accusations and court cases would have been justified if the law was applied to everyone equally.

Indeed, there is a solid case in Vanadzor which is being overlooked, because the culprits are Pashinyan’s cronies. There, a nurse, Armine Poghosyan, with an impeccable record of professional performance, has been asked by her superior to resign, because she ran for parliament as an opposition candidate. Ms. Poghosyan claims that the hospital’s acting director told her that the governor of Lori Province asked her to quit her job. She said he threatened to sue her if she were to reject the demand. The accusation was verified by the party delivering the threat, yet no one was held accountable, as Lori is under the control of Civil Contract.

These kinds of inequities play into the hands of the opposition.

On the other hand, the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) has drafted legislation to purge Armenia’s courts. The SJC is headed by a controversial former prosecutor named Gagik Jahangiryan, who said in a recent story in Azatutyun, “Those people who have committed crimes against justice must definitely be purged.”

This law also is intended to be used to eliminate judges who do not fall in line with the ruling party’s policies.

Incidentally, it was reported in the press that “Jahangiryan himself was at odds with human rights activists when he served as Armenia’s chief military prosecutor from 1997 to 2006. They accused him of covering up crimes and abetting other abuses in the armed forces throughout his tenure.”

We had our own run-in with Mr. Jahangiryan when he held a sham trial in 1996 to hand over our sister publication, Azg daily, to a group of renegades, triggering an international outcry throughout the local media and Western embassies. Later on, another judge overturned the ruling and the paper was returned to its rightful owners. For the moment, we will refrain from going into the motivations for Mr. Jahangiryan’s unsavory actions.

We can see that Armenia does not have a mature opposition to help the parliament to conduct its normal business, nor a government devoid of traditional cronies, endemic in Armenia. Had Pashinyan’s team demonstrated the magnanimity of a winner, an entirely different political atmosphere would now reign there.

Still, Armenians have no other choice but to support the present government, while holding it accountable for its mistakes. The current government represents the will of the voters. No one yet has conducted a poll to find out what the other 50 percent of the voters who did not show up to vote think.

Remembering the days I spent in Yerevan, one fervent hope is framed in my mind: I hope the Titanic does not sink again.