How do optimates prevent the establishment of ochlocracy?

In ancient Rome, the concept that we conventionally translate as “power” had different nuances and was defined by different words: auctoritas (authority), potestas (power), dominium (possession), imperium (command, order).

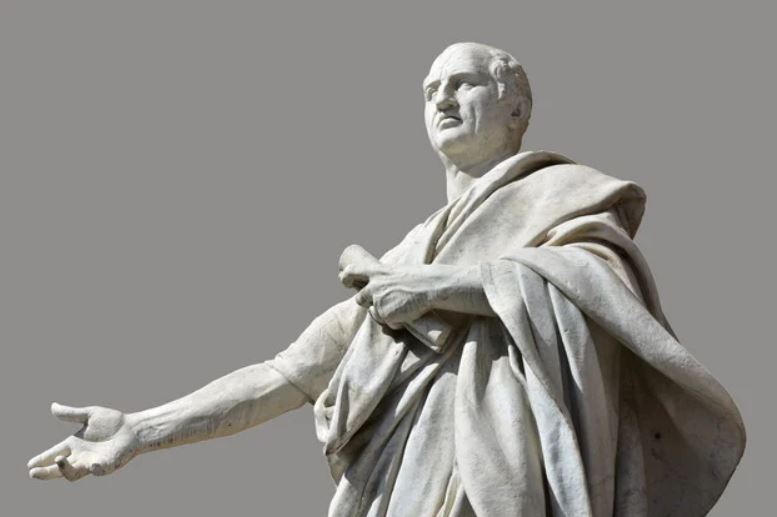

To avoid confusion, consider the first two. Especially since it was in the first century BC that the Roman orator and philosopher Cicero turned his attention to them, one of the most famous sayings of which sounds like this: potestas in populo, auctoritas in senatu. In other words, power is from the people, and authority from the Senate. Moreover, the senate was not a legislature for the ancient Romans; it was a club of respected, educated, and well-to-do people that formed the country’s policies as a result of discussion.

Of course, Cicero described the purely theoretical, ideal situation in practice, when the republican order in Rome was replaced by an empire, the monarchs tried to pass the Senate to their loyal people, in modern terms, “on the list of the ruling party.” There is even a myth that Caligula wanted to make his horse, Incitati, a senator. But first, in reality it is not about the senator, but about the position of consul. Secondly, the emperor did not fulfill his intention. According to one version, he was just joking, hinting at the ignorance of the consuls.

Read also

Cicero himself had a special role for the consuls. He considered the system of government presented in “pure form” to be harmful, and suggested a mixed form, developing the ideas of the Greek Polybius. According to that, the system should be tri-level with two consuls embodying the monarchy, the senate representing the optimates (aristocracy), and the People’s Assembly, through which democratic norms operate, naturally for free people, not slaves.

Later, in terms of “terminology,” everything got mixed up. For example, the power of a country is described in English as authority, and in Italian potenza, and the two Latin roots, so to speak, carry power “in different directions.” But the problem is not so much in the formal application of Cicero’s formula as in the unity of power of the people, and the legitimacy and authority of the aristocracy. The first, without the second, leads to ochlocracy (mob rule), and the second, without the first, turns into various kinds of arbitrariness of the “upper.”

Different countries try to solve these problems in different ways or do not solve them at all. There are institutions in the West that perform the functions of “senators’ authority.” They are independent of the government and political forces, but often feed on states. (In countries like ours, where the government identifies itself with the state, any government official will shout, “How can I pay to be criticized?”). They can be think tanks, universities, media outlets, individual intellectuals. For example, the American linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky, with his extreme left-wing views close to anarchism, influences American politics, although it is clear that no statesman or politician in the United States will directly implement Chomsky’s ideas. Thus, the idea of the “senate” does not have to be formulated at the institutional level, the important thing is the state tradition, the public perception.

In the post-Soviet country, there is no such idea at the level of government or public perception. Of course, we can not say that the situation is the same everywhere. To follow the example, let us note that thousands of people in neighboring Georgia consider themselves the descendants of an aristocrat or a prince, not in the sense that their ancestors were rich or in great power, but they followed certain ethical norms and believed in certain spiritual values that today’s people are proud of and try to follow.

There are no such nuances in public thinking in Armenia. There are no reputable groups or individuals either. Discrediting any opinion with an ad hominem argument (moving the conversation to a personal level) is one-on-one. The cruelty of the Armenian reality is that people “can” say to each other, “Who are you to speak?”

In the 20th century, it seems to me that we did not have a more famous Armenian writer than Hrant Matevosyan. But it is not the case that during Kocharyan’s rule the language of those who ousted the government was not used to write or say disrespectful words to him.

Attempts are also being made in Russia, Armenia, and a number of other countries to create structures similar to the “authoritative senate.” In our country, it is called the “Public Council.” But I think everyone will agree that this structure does not serve its purpose, and it is no coincidence that the council was headed by Serzh Sargsyan and then Nikol Pashinyan, a staunch supporter.

This mechanism does not work in our country. It is only necessary to add that we have many worthy people both in Armenia and in the Diaspora. But how to make them auctoritas, I do not know.

Aram Abrahamyan