by Edmond Y. Azadian

A tripartite meeting with Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan had been anticipated on the first anniversary of the ceasefire declaration, on November 9, 2021. That meeting was supposed to mark the culmination of the respective countries’ deputy prime ministers’ work over the last year.

Presidents Vladimir Putin and Ilham Aliyev and Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan were to sign an agreement about the unblocking of roads and lines of communication in the Caucasus.

Read also

However, that meeting was postponed indefinitely because of Azerbaijan’s renewed aggression against Armenia. Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Sergey Overchuk had announced that all roads and communication lines that would be unblocked would operate under the sovereignty of their respective countries. This declaration was supposed to be the culmination of the deputy prime ministers’ work and yearlong negotiations, which implied also the consent of the Azerbaijani side.

However, Azerbaijan’s aggression and Aliyev’s and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s repeated insistence on the Zangezur Corridor at the conference of the Organization of Turkic States meeting in Istanbul earlier this month shattered those hopes and made it abundantly clear that Moscow and Yerevan were operating only under the illusion that they had an agreement at hand.

After dashing all hopes for a timely settlement in the region, the situation has become unexpectedly volatile. This precariousness led to an announcement by the office of Charles Michel, the president of the European Union, that Pashinyan and Aliyev had agreed to meet on December 15, on the sidelines of the EU’s Eastern Partnership Summit in Brussels. A spokesman for Mr. Michel stated, “The goal is to bring Pashinyan and Aliyev to the same table for confidence-building measures.”

The news about Pashinyan’s trip to Brussels, compounded by an earlier commitment by Armenia’s premier to participate in President Joe Biden’s conference on democracy December 9-10, triggered the pro-Kremlin news media in Yerevan and Moscow to accuse Armenia’s foreign policy of shifting toward the West.

That was followed by news that the Putin-Aliyev-Pashinyan summit had been finalized to take place in Sochi on November 26 to preempt any unforeseen developments in Brussels.

Every move that the minor players decide to make spurs the major powers to vigilance in order not to let their relationships slip through their fingers. Moscow is particularly concerned that the political agenda in the Caucasus may come under the control of the West.

One level of the Russia-West competition is the contrast between the 3+3 format promoted by the Baku-Ankara tandem, which purports to solve the problems in the Caucasus through Russia, Turkey and Iran, with the participation of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. The thrust of this format is to keep the West away from the region, a position shared by Russia, Turkey and Iran, to the detriment of Armenia and Georgia.

The recent reactivation of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group at least will entertain the issue of Karabakh’s status, which Moscow would like to postpone indefinitely, while Baku and Ankara have already declared that the issue was settled by the 44-day war.

Moscow’s possessiveness on Armenian issues is manifested in a statement by Stanislav Tarasov, an editor of the Russian Regnum News Agency, who asks what the agenda of the Brussels meeting might be. If the issue of demarcation and delineation is to be discussed, he says, that cannot happen without Moscow’s participation.

Russia has demonstrated that it has a perplexing concept of its role as Armenia’s strategic partner; when Azerbaijan has occupied 41 square kilometers of Armenia’s sovereign territory and continues toward the border crossings in Syunik and Gegharkunik and Armenia appeals to this ally for help, the obscene answer is that Armenia has not formulated its appeal in writing!

Russian peacekeeping forces are supposed to be stationed between the opposing parties in Armenia to prevent bloodshed. Instead, the Russian peacekeepers are nowhere to be found during Azerbaijani incursions, but they arrive after the shooting stops to count the number of the dead and expect gratitude from Armenia for the service, suggesting that the worst was averted because of the presence of Russia’s peacekeeping mission.

In reality, help should have already been on its way thanks to the stipulations of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), headed by Russia, and of which Armenia is a member, and by the immediate mobilization of the 102nd Russian base in Gyumri.

This aversion by Russia to get its hands dirty in Armenia is seriously debated and defended by Kremlin advocates, like Sergei Markedonov, the leading researcher at the Euro-Atlantic Security Center of the MGIMO Institute for International Studies in Moscow.

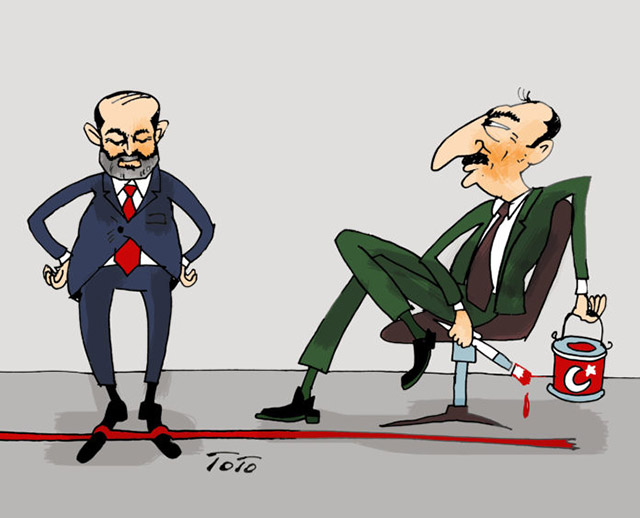

Here is Markedonov’s inverted logic for the strategic partnership: “Turkey is a consistent supporter of Azerbaijan, while Russia is a moderator in the conflict, whose moderation is accepted by Baku, Yerevan and the OSCE Minsk Group.

“In this light, the positions of Moscow and Ankara should be compared, without going beyond the framework of correctness, in my opinion, only in the full understanding of these fundamental differences between Turkey and Russia. … And it was Russia that contributed to the suspension of the hostilities on November 16.”

Herein lies the basic fallacy of the Russian logic: Russia had to prevent the hostilities in the first place rather than contributing to their suspension, after so many casualties were incurred.

Russia itself is in a precarious position vis-à-vis Azerbaijan, because its lack of a mandate to introduce its peacekeeping forces on the latter’s territory is its Achilles’ heel. At Erdogan’s instruction, Aliyev thus far has refused to sign that mandate, keeping the legality of the peacekeeping forces in the region in limbo. That is why Moscow feels that it has to cater to Baku, to Armenia’s detriment, whereas when Russian bases were ousted from Georgia and Azerbaijan, Armenia was the only country that gave a military foothold to Russia in the Caucasus, allowing Moscow to project is power all the way to the Middle East. If that foothold is not maintained for its own sake and Moscow’s sake, it may spell disaster for both parties.

Recently, Turkish Nationalist Party leader Devlet Bahceli offered a map of “Great Turan” to Erdogan, who proudly touted it to his public. That map included some territories of the Russian Federation in the future Turanic Empire, which Mr. Erdogan is dreaming of and planning to build. In view of that scene, President Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov offered a mild historic rebuke. What Peskov and his master need to do is to draw some lessons from history. Today’s Russia is akin to the Byzantine Empire, whose leaders constantly weakened medieval Armenia, which served as a buffer state on the peripheries of their empire. Eventually, the Byzantines brought down the Armenian Bagratid kingdom and took over the capital city of Ani in 1046, while the Seljuk Turks were advancing toward Asia Minor from their Central Asian base.

After the demise of the Bagratid buffer state, the Seljuks in three centuries moved to conquer Constantinople itself in 1453. Erdogan likes to think of himself as the reincarnation of Sultan Mehmed II and does not hide his intentions from anyone, including Russians. Great Turan is not only an existential threat to Armenia, but also to Russia, since today’s political developments move at a faster pace than in medieval times. Moscow’s shortsighted expediency may cost it dearly in the near future as well as the long run.

Charles Michel will certainly promote the Minsk agenda on December 15 and Mr. Aliyev is participating in the meeting with the hope that he can shift the agenda in his favor thanks to the nation’s oil production.

Moscow eventually may play an active role in the Minsk format by steering away the agenda from Karabakh status to humanitarian issues like the release of Armenian POWs and protection of cultural and religious heritage now under Azerbaijani rule. Moscow had committed to settle those issues by signing the November 9, 2020 declaration but so far it has failed to deliver on its commitments.

The Brussels meeting is only one step on the difficult road ahead. No one knows how the demarcation and delimitation will be conducted and what kind of a map will emerge from that process.

Aliyev has surrendered his country’s sovereignty to Turkey in return for his personal rule in Azerbaijan; it is Turkey that is calling the shots in Azerbaijan. Ankara has a never-ending list of demands from Armenia. For a long time, Ankara’s condition for establishing ties with Armenia was the settlement of the Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan’s favor. Now that the conflict has been settled to Ankara’s pleasure, Erdogan has been insisting on the opening of Zangezur Corridor. Armenia is dead set against the idea; even if Yerevan gives in, Ankara will move the goal post and demand something even more outrageous. Therefore, it is foolhardy for Armenia to claim, as it just did, that it has no pre-conditions to normalize relations with Turkey. Unless Armenia fails to put its own conditions on the negation table, there will be no limit to Mr. Erdogan’s appetite.

In order to be able to cancel out Turkey’s preconditions, Armenia must come up with its own conditions, even going beyond the realistic issues, like adding the abrogation of the Kars Treaty of 1921, along with the recognition of the Armenian Genocide.

We are painfully reminded that Armenia’s diplomacy will not be able to match that of its enemies. The meeting with Brussels may be organized with the best of intentions by its hosts, but the only definite expectation is outrageous words and deeds by Azerbaijan and its Turanic overlord.