Soviet traditions and challenges facing intellectuals

According to opinion polls, the vast majority of Russians support their country’s “special operation” in Ukraine. By the way, the “special operation” mildness and the “euphemism” are becoming more and more ridiculous. Such “actions” should take hours, in extreme cases, days. But when the “operation” lasts a month, it is already a long, continuous process. Although the Kremlin says that everything is planned that way, to be honest, I do not believe it. There are not so many casualties during the “special operation.”

But there is “unanimous support.” And, according to some data, it reaches 68%. I think sociologists are able to truly get that number, but the question is, how does that number come about? In Soviet times, when people were asked about the factory, such as “how do you spend your free time?”, people answered that they go to theaters, visit museums, and read fiction. Then, with all “good faith,” those numbers were published. But did they reflect people’s real preferences? The problem is that the questions are constructed in such a way that answering them in a different way would mean, at best, getting out of the comfort zone and, at worst, being in the spotlight of law enforcement. In a country where the word “war” is banned, one must have some civic courage to say “I am against the war.”

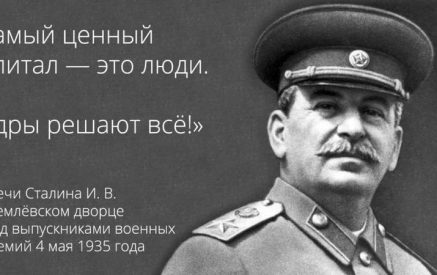

And so, if the average Russian is asked, “Do you support a special operation aimed at the denationalization and demilitarization of Ukraine?” (perhaps the question is not worded that way, but the context means that), they will not likely answer “no,” because in that case, they will be a Nazi and a militarist. Of course, the Soviet traditions and stereotypes created by them also play a role. “I, like the whole Soviet people …”, – this is how the representatives of the working class, the peasantry and the intelligentsia started their pre-written speeches in the “Vremya” program. They could “unanimously welcome” the next speech of “dear Leonid Ilyich” or “unanimously condemn” any “anti-Soviet” behavior of the “derelict” (that is, the one who separates themselves from “the whole Soviet people”). And now Putin, his administration, and propagandists are coming to the “pillar of contempt” for public figures who have been “sold to the West” and “betrayed the homeland” who dare to condemn the war.

Read also

Most of the Russians we see on the streets of Yerevan (mostly under the age of 40), I suppose, do not think in terms of that conformism, and it is no coincidence that some of them demonstrate in front of their embassy protesting against the war. Most of our guests are from other “non-Soviet” cultures. But it should be noted that even in Soviet times, not everyone “unanimously condemned” or “unanimously” welcomed. And I am not talking about dissidents in this case. Glory and honor to them, but here I mean people who did not have political or, moreover, “anti-Soviet” goals, but were guided only by their conscience and human values. Such was the case with the world-famous cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who took refuge in Solzhenitsyn in his summer house and wrote a letter to Brezhnev in defense of the writer, knowing full well that the Soviet authorities would punish him for it. (By the way, the “Soviet” went further, eventually depriving him and his wife of Soviet citizenship). The notion of “Russian intellectuals” is now being discredited. I think it is being done specifically to justify extremely low moral standards and extreme conformism. But it is also an important event for our Armenian culture. They are people who, regardless of nationality or profession, have been able to preserve the human face in Stalin’s, Brezhnev’s, and Putin’s Russia.

There are significant differences between Soviet Russia, Soviet Armenia, Putin’s Russia, and modern Armenia. But there are similarities that make thinking people have the same demands: not to merge with the majority, not to be afraid, and on the other hand, not to be offended by it. Just go your own way.

Psychologist Alexander Asmolov, in the context of this topic of “unanimous support,” recalling the years of stagnation in the ‘70s, quotes the words of the poet Andrei Voznesensky: “It seems to me that “we” are not few in Armenia. By “we” I do not mean those who think like me, but those who think they can think in any way. In that sense, we are “like-minded.””

Aram ABRAHAMYAN