by Edmond Y. Azadian

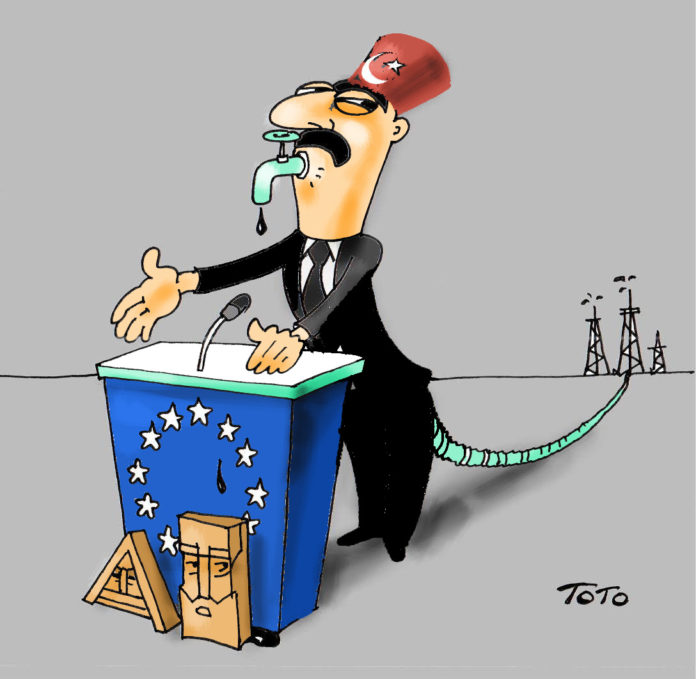

The forthcoming Armenia-Azerbaijan negotiations are the extension of the Armenian-Turkish talks, which started with the assurances that there will be no preconditions. Ankara moved the negotiations to a related field, where pre-conditions emerged. While Turkey was insisting on no preconditions, in the meantime, it stated that it was coordinating those talks with Azerbaijan.

After two rounds of Turkish-Armenian talks, from which “positive signs” emerged, it looks like these talks are temporarily suspended, pending the outcome of talks between Nikol Pashinyan and Ilham Aliyev in Brussels on April 6 (after press time). This way, Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan is off the hook vis-à-vis the Biden administration, which initially had asked Mr. Erdogan to normalize its strained relations with Armenia. Should the Pashinyan-Aliyev talks fail to produce any concrete results, Turkey will have ample opportunity to blame the Armenian side.

Read also

In preparation for the April 6 summit, Pashinyan made an extensive presentation before Armenia’s Security Council, where he outlined the major issues. He revealed that the country faces a tough situation, as Baku has sent a five-point peace plan, with a warning that if a peace treaty is not signed immediately, the next step would be war.

Yet many outstanding issues between the two countries have not been resolved and conditions set by the November 9, 2020 tripartite declaration have not been met: the refugees have not been resettled, the Armenian POWs have not been released, and Azerbaijani forces have not been moved out of Armenia’s Sev Lij region and other border areas, among others.

Yerevan has agreed to the negotiations, even though one of the five points in the Azerbaijani proposal is the mutual agreement to the territorial integrity of both countries.

This signifies that Armenia will have to agree to the premise that Karabakh is part of Azerbaijan. In short, the destiny of the Karabakh people is on the chopping block.

Turkey and Azerbaijan are making haste to create irreversible wins on the ground, now that Armenia is in a weak position after its defeat and Russia and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) are fully engaged in the Ukrainian crisis.

Recently, a British military delegation reportedly visited Azerbaijan, which may signal the latter has a free hand to possibly open a second front against Russia by attacking Armenia in yet another case of a global powerplay.

With the background of a pointed reprimand from the US State Department to Baku, blaming the latter for border conflict escalations, and despite the US’s critical position on Azerbaijan’s cultural genocide in the occupied territories, the recent waiver of Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act should not be construed as an anti-Armenian political move because that reflects America’s overall strategy of containing Russia. Armenia is simply part of the collateral damage.

The US or the Western powers do not have the wherewithal to neutralize or to push Russia out of the Caucasus. That role has been relegated to Turkey, which has become the necessary evil for both opposing camps. That is why all its transgressions are forgiven; for example, after blaming Russian for its aggression in Ukraine and voting against Russia for the annexation of Crimea, Erdogan has the guts to refuse to abide by the sanctions imposed on Russia by the West.

Turkey operates in a space of impunity it has created for itself. Therefore, to pin hopes on any major country to help Armenia against Turkish and Azerbaijani aggression is unrealistic.

We have to admit grudgingly that Pashinyan’s trip to Brussels can amount to nothing but signing off on another document of capitulation, similar to the November 9, 2020 declaration.

The only guarantee to preserve Armenia’s — and by extension Karabakh’s — security and sovereignty was the armed forces, not necessarily by winning a war but by deterring one.

During the last war, the Armenian armed forces fought valiantly for 44 days, despite spy networks, defections and the malfunctioning of its Iskandar missiles. Since the war, four chiefs of staff and three ministers of defense have been charged, which does not bode well.

Turkey and Azerbaijan have chosen Brussels for the April 6 summit to spite Moscow, that city being home to NATO headquarters. That is why President Putin has been frantically calling President Aliyev and Prime Minister Pashinyan. Even after calls to each party, Putin called Pashinyan again, certainly to warn him not to cross certain red lines.

Incidentally, the war in Ukraine is a double-edged sword against Armenia; if Russia wins an overwhelming victory, the chances are that the prospect of a “union state” will have a new lease on life and Armenia will become a candidate for membership. If, on the other hand, Russia is humiliated there, the West will push it out of the Caucasus. In that scenario, Armenia’s security guarantor will not be the West directly, but its surrogate in the region, Turkey. That should certainly send a shiver down our spines.

It is apropos to quote here French Senator Valerie Boyer, who, commenting on a statement in the newspaper Figaro, stated this week, “During the 202 large-scale aggression, Azerbaijan, with the support of Turkey, massacred the Armenians of Artsakh though Turkish bombs, white phosphorus and drones. The genocidal spirit has awakened in them. And the world is silently watching without lifting a finger. Encroachments continue in an atmosphere of indifference.”

Armenia’s Foreign Ministry establishment has made a practice of forfeiting its assets before sitting at the negotiation table. That happened before the Armenian-Turkish negotiations and it is happening now, in preparation for the April 6 summit. Turkey Caucasus editor at Eurasianet, Joshua Kucera, writes, “Conceding sovereignty over Karabakh would represent a dramatic turn for Yerevan. The Armenian government is effectively conceding that the Armenians will not be able to retain control of Nagorno Karabakh, paving the way for Azerbaijan to regain full control of sovereignty over the territory and boding an uncertain future for the area’s current ethnic Armenian residents. The concession has not been made explicitly but rather via a conspicuous shift in official rhetoric from Yerevan.”

To corroborate his statement, Kucera quotes Armenia’s Foreign Minister Ararat Mirzoyan: “For us, the Nagorno Karabakh conflict is not a territorial issue, but a matter of rights.”

This is setting the stage to give up Karabakh, when there are other options to explore; one such option is the principle of “Remedial Secession,” which was successfully used in the case of Kosovo, South Sudan and East Timor to attain independence. Karabakh is a perfect case given Azerbaijan’s genocidal policies.

“Rights” are pretty vague formulations, wherein the OSCE can easily situate certain cultural rights after placing the head of the Karabakh people under Ramil Safarov’s axe. Of course, the latter case is a symbolic one, dating back to 2004, in Budapest, when Safarov beheaded an Armenian soldier, Gurgen Margaryan, a fellow participant in a NATO-sponsored program. Safarov was arrested but repatriated to Azerbaijan, where the Hungarian government was assured he would head straight to prison. Instead, he received a hero’s welcome, a full pardon and a promotion.

When confronted with a resolute international community, Aliyev can even buy the principle of rights.

Confusion and desperation are spreading amongst the population of Karabakh. Officially, 117,000 Armenians live in that enclave. Their tenacity is amazing: despite all odds, they are taking care of their land. Every citizen in Karabakh is a vote for the survival of that self-declared republic. There are still 22,000 Karabakh refugees in Armenia who are willing to return to that devastated land and defend it. Instead of helping them, Armenia’s government is distributing funds to political parties outside the parliament for buying influence. Again, domestic petty politics take priority over the very existence of Karabakh.

There is uncertainty in and around Karabakh. President Arayik Harutyunyan of Karabakh has appealed to Moscow to increase the number of its peacekeepers there to enhance security. As Ossetia prepares to join Russia in the Union State, that initiative has fueled the imagination of some Karabakh politicians. Hayk Khanumyan, the Karabakh minister of local government and public infrastructure, said in an interview, “This is what is fueling calls by some Karabakh Armenians for a referendum on becoming part of Russia.”

Unfortunately, Karabakh is not the endgame in Turkey’s and Azerbaijan’s political playbook. They have been brutally honest in their plans, and arrogantly vociferous that after Karabakh, it is Zangezur, and perhaps all of Armenia itself, which Mr. Aliyev calls historic Azerbaijan. Zangezur is a precious slice of land for Azerbaijan, a gateway for Turkey to unite Central Asian republics to its Turanic empire, while for the west it is the final state of encirclement and containment of Russia.