by Edmond Y. Azadian

The devastating effects of the 44-Day War and the turmoil in the Caucasus region dictate some necessary measures for Armenia: internal unity and independent and objective evaluations of the country’s problems and actions derived from those evaluations. The first objectives which come to mind are national unity, mutual tolerance and a consensus on an agenda of national recovery.

We have advocated time and again that for a country like Armenia, so divided and polarized, the road to recovery would be the creation of a truth and reconciliation commission, along the lines of the South African model, to be able to come out of the quagmire and address the basic problems of the country.

Read also

It is true that after the war, in the 2021 elections, 54 percent of the voting public supported Nikol Pashinyan’s My Step coalition. Pashinyan himself, like everybody else, knows full well that in that election, people voted against his opponent Robert Kocharyan and not necessarily for Pashinyan. That kind of victory does not amount to the mantle of legitimacy or mandate, which the current administration is claiming to justify its actions.

The pro-government media continues to repeat ad nauseum that “the people voted for us and they rejected the opposition.” Another simplistic accusation against the opposition is that all the problems of the country stem from 20 years of misrule – even the war, which took place under Pashinyan’s watch.

The opposition certainly must bear its share of the blame for the country’s problems, because of unchecked corruption and abuse of power. At this point, perhaps it sounds politically incorrect to state that despite the corruption, no major war happened on a scale comparable to the last one, which brought about an existential threat to Armenia’s doorstep.

Some pro-regime pundits, state, tongue in cheek, that as long as Robert Kocharyan is on the political scene, Pashinyan has a good chance to be reelected. That is an accurate statement, because Kocharyan’s name is tainted by many scandals, including his accumulation of tremendous wealth in a poor country, the October 27, 1999 parliament massacre, which helped his political survival and his hubris in eliminating Karabakh from the negotiation table of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group.

No one could state with certainty if Pashinyan could run a more efficient government if it were not hampered by the pandemic and the war. But following the Velvet Revolution, people did not find a noticeable improvement in their economic situation, nor did the pace of emigration slow.

Since May 1, the opposition has been engaged in massive demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience. The movement is led by the Hayastan (Armenia) and Pativ Unem (I Have Honor) coalitions, respectively headed by Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan. The former presidents are never seen together during the demonstrations. Those visible on the stage are the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnak) leaders Ishkhan Saghatelyan, Gegham Manoukyan and Armen Rustamyan, and former head of the National Security Service Artur Vanetsyan.

One of the earlier statements by Vanetsyan has already determined the outcome of the movement. Indeed, at an impromptu press conference, he stated, “If the demonstrations do not yield the expected result, I have no intention to return to parliament.” If one of the leaders of the movement casts doubt on the outcome, right at the onset, that movement is doomed.

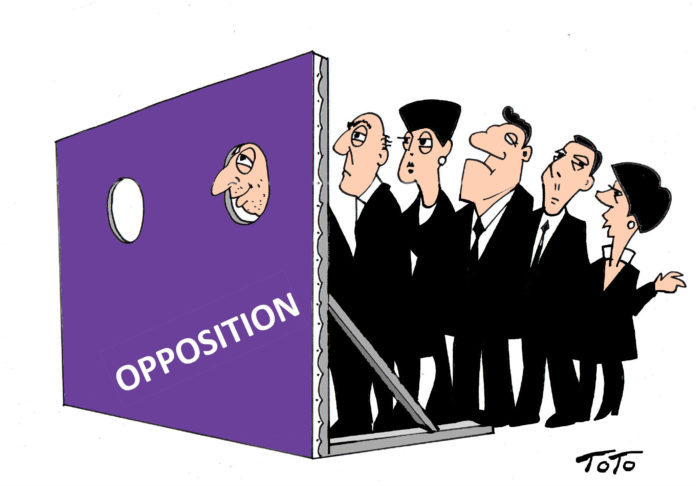

The opposition has been mimicking the tactics that brought Pashinyan to power, but the crowds following those leaders have yet to reach a critical mass to be effective. The closing of streets and storming government buildings have been met with police brutality that has drawn criticism from Chatham House in the UK and the local human rights defender.

One of the main reasons the movement does not get traction is the lack of catchy slogans as well as a clear agenda. To unseat Pashinyan when there is no viable candidate among the opposition leadership does not inspire confidence. Nor does the accusation that Pashinyan will give Karabakh to Azerbaijan make any sense, because Pashinyan does not any longer have control of that enclave, 75 percent of which is occupied by Azerbaijan and the rest by Russian peacekeepers. The latter are the ones that call the shots at this point.

The opposition had been agitating for a long time. What brought about the launch of the movement was Pashinyan’s long defeatist speech in the parliament on April 13, when he stated that the international community was expecting Armenia to “lower the bar” on its expectations. This comment was interpreted as the surrender of Karabakh. Ever since, every statement by the government supplied further ammunition to the opposition.

The upcoming fateful negotiations with Azerbaijan are providing yet another opportunity to the opposition. Baku has come up with a five-point proposal, which the Armenian side has accepted while submitting its own six-point list, which has been kept secret so far. But a few days ago, Ambassador-at-Large Edmon Marukyan finally made it public during an interview with Petros Ghazaryan. Basically, those six points refer to the security and the rights of the Karabakh people, a vague formulation which can be interpreted in any way. There is not even a mention of remedial secession, which can be the only viable option.

National Security Commission President Armen Grigoryan reassured the public that both Armenia and Azerbaijan are silent on the specifics of the enclave issue to protect the integrity of negotiations. However, right after that, Khalaf Khalafov, Azerbaijan’s deputy prime minister, made public claims for some enclaves from Armenia, before even sitting at the negotiation table.

The opposition is asking outright for Pashinyan’s resignation, without even holding early elections and proposes to form a unity government, comprising 250 technocrats. The names of those technocrats have yet to be released.

Basically, what the opposition is suggesting is “let Pashinyan resign, then we will come up with something.” This is not a national agenda which will bring together the country. And that is why the movement is not going anywhere.

The first president, Levon Ter-Petrosian, warned that the opposition’s actions will only hamper the upcoming negotiations with Turkey and Azerbaijan. However, the government and pro-government forces are comfortable as long as Kocharyan and Sargsyan are in the mix. The people are particularly scared of Kocharyan’s intentions to see Armenia in a union state with Russia, thus losing its sovereignty.

What the current administration fears most is the emergence of a third party, which is not tainted by the former corrupt regime and has knowledge of statecraft, which Pashinyan and his cadre lack. And indeed, there are names being circulated, including Avedik Chalabyan and Arman Tatoyan, both of whom have high standing among the public. That is why Tatoyan is being harassed and Chalabyan is currently under arrest on trumped-up charges.

Chalabyan is the head of a small political party. He is also the co-founder of a private charity helping Armenian soldiers and residents of border villages in Armenia and Karabakh. He is very articulate and knowledgeable on political and military matters. He has supported the opposition, but his name has not been tarnished in any corruption schemes. This is the type of person who scares the government and provides an alternative to Pashinyan’s inept group whose merits and education were gained in Pashinyan’s long march from Gyumri to Yerevan.

Pashinyan has to watch the rise of people like Chalabyan with dread while the population hopes for the emergence of a third force.