Statement by Dr Hans Henri P. Kluge, WHO Regional Director for Europe

Good day to one and all.

Just yesterday, WHO announced that next week we will convene an Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations to advise on whether the current spread of monkeypox in non-endemic countries constitutes a public health emergency of international concern.

Europe remains the epicentre of this escalating outbreak with 25 countries reporting more than 1500 cases, or 85% of the global total.

Read also

The magnitude of this outbreak poses a real risk; the longer the virus circulates, the more it will extend its reach, and the stronger the disease’s foothold will get in non-endemic countries.

Governments, health partners and civil society need to act with urgency, and together to control this outbreak; and there are three basic steps needed.

First, carry out enhanced surveillance, contact tracing and infection prevention and control.

Strong surveillance and diagnostic systems in several European countries – along with swift information-sharing mechanisms – have ensured that the outbreak has been rapidly reported and communicated.

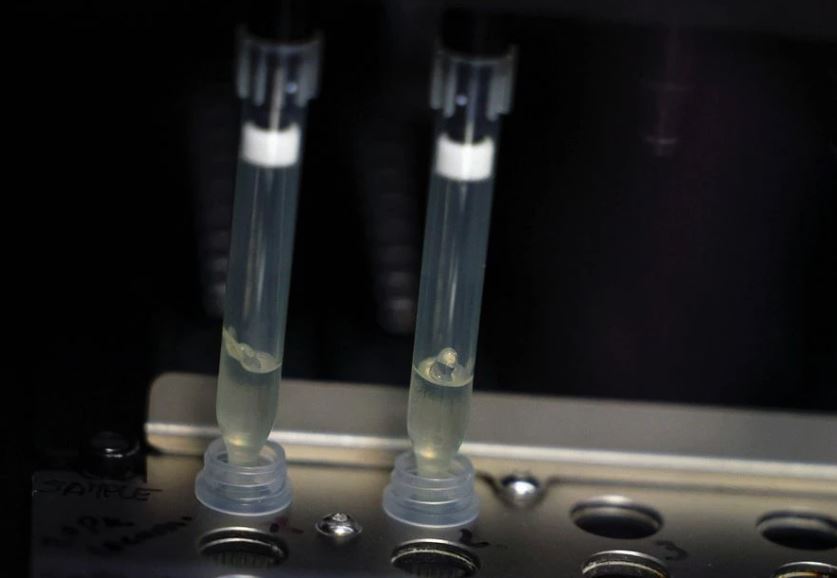

However, we are already seeing significant gaps in our ability to respond that need to be filled. As a top priority, WHO has released emergency funds to rapidly establish monkeypox virus identification and sequencing in countries that have not yet got the tests and lab supplies to detect the virus in their laboratories.

Still, even without all tools available to us right now, we have what we need to identify cases and prevent onward spread.

Clinicians need to know what they should look out for and how to manage suspect cases. The general public also needs to know what to look out for, and what they should do – or not do – if they think they have monkeypox.

Once identified, patients with suspected or confirmed monkeypox should be isolated until their symptoms are fully resolved, with the necessary infection control measures and the support they need to see them through to recovery. We need to identify close contacts of cases and support them as well, to self-monitor for 21 days for any early signs of monkeypox, such as fever.

So far in Europe, the majority – though not all – of reported patients, have been among men who have sex with men. Many – but not all patients – report multiple and sometimes anonymous sexual partners. Identifying, tracing and notifying sexual partners quickly is therefore often difficult, but remains critical in order to stop onwards spread.

But – and this is important – we must remember that the monkeypox virus is not in itself attached to any specific group. Stigmatizing certain populations undermines the public health response as we have seen time and again in contexts as diverse as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and COVID-19. Monkeypox will be opportunistic in its fight for survival, and its spread will depend on the conditions provided to it.

The second step to curbing transmission is intensive community engagement and clearer communication.

We have entered the summer months in the northern hemisphere, with summer tourism, various Pride events, music festivals and other mass gatherings planned across the region. These events are powerful opportunities to engage with young, sexually active and highly mobile people. Monkeypox is not a reason to cancel events, but an opportunity to leverage them to drive our engagement.

WHO and health partners are reaching out quickly to communities, event organizers and dating apps to provide clear information to raise awareness about monkeypox infection and strengthen individual and community protection.

To reiterate, the immediate need is to contain this outbreak by stopping human-to-human transmission, and for this, the first two steps are key.

The third step is genuine and unselfish regional collaboration – urgently now and in the longer term.

Even as we address the present, we must look to the future, while drawing upon lessons stemming from a global crisis still very much with us – COVID-19.

For decades, monkeypox has been endemic in parts of western and central Africa – and for decades it has been neglected by the rest of the world. Now that it is in Europe and elsewhere, we have seen yet again how a challenge in one part of the world can so easily and quickly be a challenge for all of us – and how we must all work together to ensure a coordinated response that is fair to one and all, especially the most vulnerable. But have we truly learned these lessons?

There currently are limited amounts of vaccines and antivirals for monkeypox, and limited data on their use. Mass vaccination is not recommended or needed at this time. Targeted vaccination, either before or after exposure to the virus can benefit contacts of patients, including health-care workers. Yet, we are already seeing a rush in some quarters to acquire and stockpile these.

But what about those countries in Africa where monkeypox has long been endemic – should they not be part of any global strategy to address the disease? Once again, a “me first” approach could lead to damaging consequences down the road, if we do not employ a genuinely collaborative and far-thinking approach. I beseech governments to tackle monkeypox without repeating the mistakes of the pandemic – and keeping equity at the heart of all we do.

At this early stage of the monkeypox outbreak, our best tool really is our ability to generate and share critical knowledge across borders and across communities and population groups.

The diversity of the European Region means huge opportunities to leverage knowledge, skills and resources – pooling the capacities across public health institutions, to the benefit of the whole Region.

Indeed, united action for better health in Europe has never been as critical as today. I thank my co-panellists today for joining forces with us in this regard.

Thank you.