About a hundred years ago, the famous American literary critic, Cambridge University professor Irving Babbitt wrote: “Economic problems are really political problems, political problems are philosophical problems, and philosophical problems are religious problems.”

Why is that so? I think the reason is that both economic, political and philosophical problems are related to man, and man is the only representative of nature that does not obey purely natural patterns. The behavior of individuals, human groups, and societies cannot be explained by expediency alone.

Suppose, under some circumstances, it is appropriate for us to eat each other. Why don’t we do that? We are limited by our belief in certain principles. And this is where the problems begin, which the Cambridge professor calls religious. Pandemics and wars that have plagued humanity in recent years, put the eternal problems with unprecedented sharpness: what is more important: the person or the economy, the person or the state, the person or the progress?

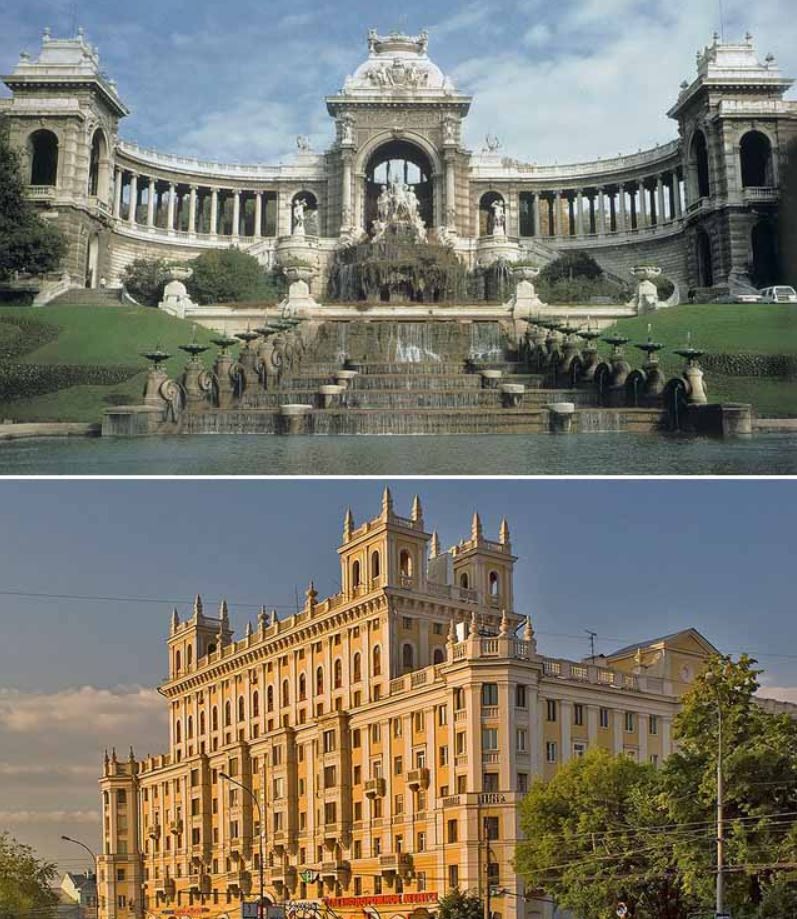

There are no easy answers here. But the general principle should be the following: disregarding people’s interests for the sake of some other, supposedly more important principles or ideas does not lead to anything good. Have you noticed how similar in style the buildings in mid-19th century Paris and 1930s Moscow are? In both cases, Roman architecture from the first centuries AD was taken as inspiration. Because both Napoleon III and Stalin sought to imitate the imperial style, and in the capital of the empire everything should be large, monumental. Was the contempt of those two dictators for people, their interests, their rights accidental? Such “minor” problems were secondary to them if compared to the glory of the state and its progress. In other words, in this case, decisions were based on unique ideas about expediency, which were not counterbalanced by moral norms in any way.

Read also

Let me give another “architectural” example. After the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, there was a need to create a calendar and ritual system that corresponded to the new times. That task was undertaken by one of the most educated representatives of the team that won the revolution, People’s Commissar of Enlightenment Anatoly Lunacharsky, who developed the ritual to celebrate May 1 and November 7. But even for that revolutionary, the approach of the remaining, less educated, but more devoted revolutionaries, according to which they destroyed the Orthodox churches in order to celebrate May 1st, was alien. When Lunacharsky publicly complained about this barbarism, the chairman of the Moscow Council, Lazar Kaganovich, justified the practice of destroying churches with a “shocking argument”: “My aesthetics require that all the participants of the May Day demonstration, from six districts of Moscow, enter Red Square at the same time.”

The churches, it turns out, interfered with that aesthetic. Thus, people subordinated their feelings to expediency, which in this case was driven by ideology. But instead of ideology, the economic necessity, the desire to make the capital city more beautiful, or even… the development of tourism could have appeared. What was needed to build Northern Avenue in Yerevan? It was necessary to dispossess and disenfranchise the former inhabitants of that area. Many people like the “aesthetics” of Northern Avenue, and many jobs were created during the construction. Should we be guided by those considerations or by moral principles?

Or maybe there is no such dilemma? One of the most gifted students of Professor Babbitt, already mentioned, the poet Thomas Eliot, pointed out that mankind can develop both material and spiritual conditions of life, mankind can and should have its own ideas about the perfect social order, but people should not forget that the ideal and own ambitions do not match. “Our problems and difficulties are the same that other generations have faced in other times,” the poet writes, “and the way to solve them remains the same: personal self-improvement.”

Aram Abrahamyan