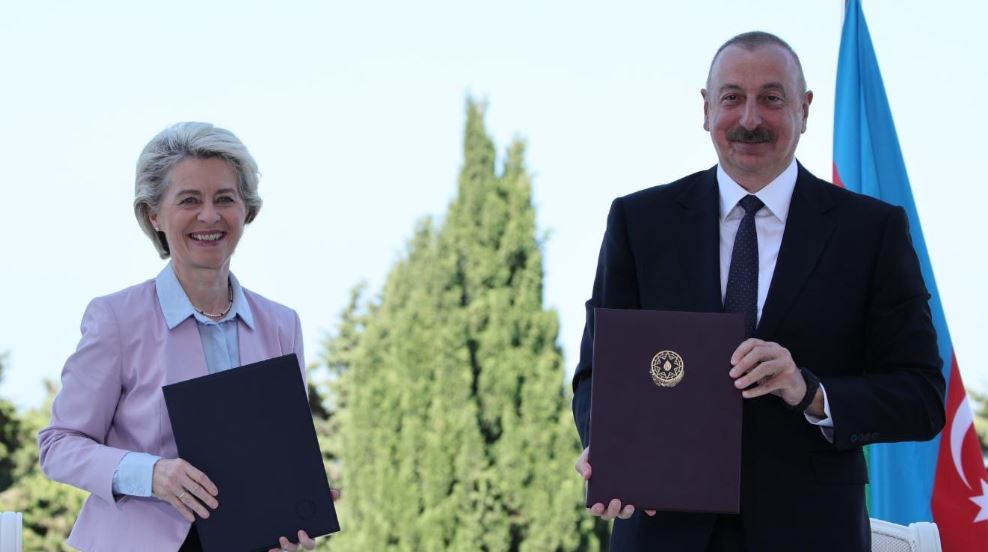

EU head Ursula von der Leyen came home from Baku with a fuel deal, but it may not be enough to fix Europe’s woes.

As the European Union scrambles to compensate for the loss of Russian gas as a result of Moscow’s aggression in Ukraine, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen Monday flew to Azerbaijan, an energy-rich Caspian nation also known for serious human rights abuses.

Read also

Her trip, which resulted in a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on “energy strategic partnership” between the EU and Azerbaijan, came three days after U.S. President Joe Biden fist bumped Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, a man he once vowed to make a “pariah” for his own brutality, as a key part of an effort to persuade Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states to ease the global energy crisis by significantly increasing their oil and gas production.

The trips by the two presidents helped illustrate the West’s desperation to bring down the global price of oil and gas – both to reduce politically toxic inflation at home and to preserve NATO unity against Russian – even if that means cozying up to notorious dictators.

Von der Leyen hailed her trip to Baku as a milestone in relations with a “trustworthy supplier” like Azerbaijan that will help the EU to move away from its dependence on Russian fossil fuels. It is part of a strategy that enjoys the full backing of the United States: one of the key points of the June 27 Joint Statement by von der Leyen and Biden on European Energy Security calls for “partnerships for diversification” of energy supplies to Europe. Azerbaijan is clearly seen in Brussels as an important player in this strategy.

Yet the memorandum with Azerbaijan does not amount to much. Its five pages read more like a long list of “endeavors” rather than firm commitments. Those notably include working towards common goals on climate and renewables. The only element that could be construed as a concrete proposal is to “aspire to support bilateral trade of natural gas, including to the EU via the Southern Gas Corridor, of at least 20 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas annually by 2027.” That would more than double the total of Azerbaijani gas exports to the EU which in 2021 amounted to 8.2 bcm. But even that target is couched in non-committal language – Baku is only supposed to “aspire” to double its gas exports. The document does not commit it to actually doing so.

The memorandum’s non-binding nature is further underscored by its final clause to the effect that “nothing in the MoU should create any binding legal or financial obligations” by the sides.

That raises the fundamental question of whether Azerbaijan can really live up to the stated ambition. As energy expert David O’Byrne notes in Eurasianet.org, Azerbaijan has “limited scope for increased production and has its own domestic demands to meet.” To cover those demands, it concluded a trilateral gas swap deal with Iran and Turkmenistan. So, ironically, the success of the EU-Azerbaijan deal depends, to an extent, on a continued implementation of Azerbaijan’s own deal with Iran – a country that the United States wishes to exclude from the international energy market through its aggressive sanctions regime.

Most important, however, according to O’Byrne, even if Azerbaijan manages to double its exports by 2027 to 20 bcm, it would still fall far short of playing any meaningful role in compensating for the potential loss of 150 bcm of Russian deliveries as soon as the coming winter.

So, for all von der Leyen’s enthusiastic rhetoric, the signed deal cannot seriously alleviate the EU’s energy woes. Instead, it was a clear diplomatic win for Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev who sees in the Russian war in Ukraine an opportunity to position his country as an indispensable partner for the EU. The pro-regime press in Baku was gushing with hyperbole about Azerbaijan’s “growing geopolitical and geo-economic clout.”

As a bonus for Aliyev, Von der Leyen avoided any criticism of Azerbaijan’s notoriously poor human rights record and its inflexible position on its Nagorno-Karabakh conflict with Armenia, notably by refusing to countenance even a limited cultural autonomy to the Karabakhi Armenians – the very issue that was at the root of the conflict some thirty years ago. Von der Leyen’s silence on these issues was strongly criticized by a number of members of the European Parliament who only in March adopted a resolution condemning Azerbaijan’s policy of destruction of Armenian cultural heritage in Karabakh, with over 600 MPs voting in favor of it, and only 2 against.

That such criticisms ruffled feathers in Baku was evident in Aliyev’s treatment of a European Parliament delegation that happened to visit Azerbaijan the day after Von der Leyen’s sojourn there. Aliyev berated the parliamentarians for supposedly acting in the interests of the “Armenian lobby.”

The European Commission may shrug off the human rights-related criticisms as an inevitable, if regrettable, cost of practicing realpolitik. With a cold winter coming, who could object to keeping European homes warm as the first priority? Yet, if “European values” are to be sacrificed, it at least should be done in a country that can deliver. Azerbaijan, given its maximum potential contribution, does not count as one.

By contrast, Iran, another energy-rich country with an abysmal human rights record, could play a much more consequential role given its much bigger gas reserves — the world’s second biggest. Should the 2015 nuclear deal, the JCPOA, not been disrupted by former President Trump’s renunciation, the EU’s energy prospects would look much brighter today. After the JCPOA was concluded, the French energy giant Total committed to 4.8 billion dollars to developing South Pars, considered the world’s biggest offshore gas field. Yet it had to withdraw its plans after Trump withdrew from the deal and imposed secondary sanctions on foreign, including European, companies investing in Iran. The Biden administration’s failure to rejoin the agreement keeps Iran’s plentiful gas reserves off the market, reducing them only to the amounts that can be exported to Azerbaijan via a trilateral swap agreement involving Turkmenistan.

This is how the U.S., despite its professed commitment to the EU’s energy security, is in fact undermining it, with the EU officials reduced to touring the world in search of some crumbs of gas in exchange for bestowing legitimacy on unsavory regimes.

This article reflects the personal views of the author and not necessarily the opinions of the S&D Group or the European Parliament.