by Edmond Y. Azadian

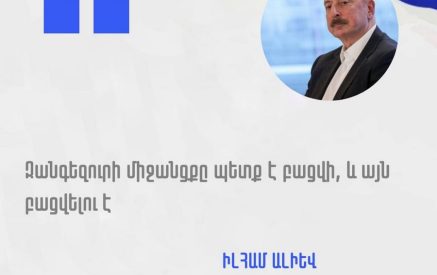

Until recently, Armenia faced a threat to its sovereignty from Azerbaijan. After the 2020 war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, President Ilham Aliyev demanded the opening of the “Zangezur Corridor,” which effectively would bisect Armenia’s territory, thereby compromising its sovereignty.

This was Aliyev’s condition for signing a peace treaty after the disastrous 44-Day War.

Read also

As if that were not enough, Mr. Aliyev invented another plan to completely take over Armenia’s territory, proclaiming it “Western Azerbaijan.” Indeed, Mr. Aliyev, trying to rewrite history, concocted a theory that the current territory of Armenia had been part of “historic Azerbaijan,” and that was enough reason for Baku to take over Armenia. It is trying actively to add to its landmass, also eying Iran’s Azerbaijan province.

Since this threat was issued by none other than the head of a state, it constituted a declaration of war, which the international community chose to ignore, in the hopes of scoring some of Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbons.

While Armenia was struggling to deal with this peril, all of a sudden, it found itself facing another threat to its sovereignty, this time around from a so-called strategic ally, Russia.

Russian foreign policy is failing to provide any help to its strategic ally and partner in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Instead, it has resorted to its ultimate weapon in its arsenal: the fear factor.

Similarly, the opposition in Armenia, having run out of any positive statements about Russia, has been using the fear factor to convince the populace and the government that Russia can use its awesome military power to punish Armenia, if the latter dares to veer away from its orbit.

That fear factor was brazenly manifested recently in a number of cases where Armenia’s interests collided with those of Russia.

Since the 44-Day War, one thing has led to another to help worsen relations between Armenia and Russia.

When Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan refused to sign the concluding statement after a CSTO session in Yerevan in 2022, because it did not condemn Azerbaijan’s actions, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, reacted angrily, justifying Azerbaijan’s war against Armenia. Tensions further escalated when Armenia refused to host the CSTO war games in January. This time around, Moscow used a stick-and-carrot policy.

Prime Minister Pashinyan had used a statement Aliyev had made to explain this non-participation. Aliyev had accused Armenia of colluding with Russia to wage a war against Azerbaijan. Pashinyan’s excuse had a cynical tenor but was a valid one. He stated that membership in CSTO not only does not help defend Armenia, but that it also makes Armenia a target for aggression, ergo Aliyev’s accusation.

At first, the CSTO Chief of Staff Col. Gen. Anatoly Sidorov announced that the CSTO will protect its member states, if necessary. In reality, it has failed to protect them when it was really necessary. Sidorov’s statement was followed by a visit by Igor Khovaev, the Russian co-chair of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group. Khovaev conveyed the Kremlin’s warning to Yerevan that “Moscow is seriously angry with Pashinyan’s statement that the Russian Federation’s military presence in Armenia not only does not guarantee but to the contrary, creates threats to Armenia’s security.”

Russia saw that as Armenia crossing a red line.

But what broke the camel’s back was Armenia’s decision to welcome, encourage and station European Union monitors on its borders.

Ever since the last war, Azerbaijan has encroached steadily into Armenian territory and occupied strategic points. Last September, that intrusion almost proved to be the beginning of a new all-out war against Armenia, as more than 200 Armenian soldiers were killed, with almost as many dead from the Azerbaijani side. Only a stern warning from Washington stopped Aliyev part-way into his campaign.

To discourage such incursions, the EU decided to station 40 civilian monitors on Armenia’s border with Azerbaijan. That certainly could not stop a new aggression, but it helped to discourage Aliyev from engaging in another adventure. Based on that experience, Armenia invited the EU monitors to be stationed over longer-term periods and in larger numbers. That is how a decision was made to station 100 monitors, along with 7 gendarmes from France and 15 retired policemen from Germany.

Mr. Lavrov said that the CSTO was now ready to send monitors but that Armenia had opted for the EU presence on its territory. That, of course, did not sit well with Moscow.

The European Parliament, along with sending monitors, urged Azerbaijan to “immediately reopen” the Lachin corridor. Its resolution also condemned the “inaction” of Russian peacekeeping forces in Karabakh and called for their “replacement with OSCE international peacekeepers.”

Moscow and Baku proffered the contention that Iran will object to the presence of European monitors close to its borders and Iran is rightfully suspicious of any Western presence close to its borders. In this world of espionage and counterespionage, anything can happen. For example, as Israeli agents use Azerbaijan to surveil Iran’s territory, similar actions may take place with the European peacekeepers. Despite Iran’s principled position on this issue, Tehran did not object to the monitors. That was perhaps a function of the recent Baku-Tehran standoff.

The first objection came from Azerbaijan, as if Baku could control Armenia’s right to host any group that it wished on its sovereign territory. But Moscow’s reaction was even more stern. Vyacheslav Volodin, chairman of the State Duma, invited his Azerbaijani counterpart, Sahiba Gafarova, on February 13, to Moscow, to sign an interparliamentary agreement between the two bodies.

Mr. Volodin, who is a close friend and associate of President Vladimir Putin, used the occasion to blast Armenia. He warned that the European bodies should not be involved in resolving Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. Sending a message to the European Parliament and the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly (PACE), he claimed that they can fan the flames of regional tensions. Armenia and Azerbaijan should stick to their agreements brokered by Russia during and after the 2020 war, he said.

“And those who make statements in the direction of European institutions, may simply lose the country,” he added.

This was a direct existential threat to Armenia. Maria Zakharova, spokesperson of the Russian Foreign Ministry, has been wincing during her sporadic press statements over the European presence in Armenia and warning that the West has been trying to push Russia out of the Caucasus.

Moscow has been shepherding Armenia into the trilateral format in order to corner Armenia and impose the bilateral will, as Russian and Azerbaijani interests coincide. But all those trilateral meetings have proven to be nothing but spinning one’s wheels.

Every time negotiations shift to Brussels, envious Russia sets up a meeting in the same format in Moscow. As a result of the recent developments, Moscow once again has invited the foreign ministers of Armenia and Azerbaijan for another round of empty talks.

Moscow seems to have made a U-turn on the issue of the “Zangezur Corridor,” in order to align with Azerbaijan’s position. As one can deduct from Mr. Volodin’s statement, Armenia’s sovereignty is the last thing that Moscow is worried about.

Russia nurtures predatory ambitions in the Caucasus and believes that Armenia has been undermining its hegemony in the region by courting Europe. Along that line, French President Emmanuel Macron’s statement at the Munich Security Conference has worried Moscow even more. The French president began his speech with the following statement: “How can we believe that the challenges of the Caucasus can be overcome by the neo-colonial Russia that I described a moment ago? I am saying this in the presence of my friend, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, with whom we will continue to stand and act.”

There is an element of truth in Russian objections. The West certainly is not involved in the Caucasus out of altruism and there is an intent there to weaken Russia’s position in the region. Russia has done everything to force Armenia to seeks its security in the West. The fear factor in the Russian threat is not mere empty talk. Russia can act and harm Armenia. Therefore it behooves Armenia to calibrate its moves in seeking security, up to the degree of tension that it can endure with Moscow. This is a delicate balancing act.

One must remember that when Georgia cast its lot with the West, Russia attacked it in 2008 and amputated some territory, while the West’s reaction did not extend beyond verbal warnings.

With the Ukraine war, Russia has become the wounded bear. Armenia needs its security to maintain its territorial integrity and sovereignty. Therefore, in its balancing act, it also needs the most flexible and thoughtful diplomacy.