by Yeghia Tashjian

The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a 7,200 kilometer model of ship network, rail and road project, was initiated in 2000 by Russia, Iran and India to facilitate trade between India, Russia and Europe. Azerbaijan, Armenia and other countries joined the initiative in 2005. This transport corridor aims to reduce the delivery time of cargo from India to Russia and Northern Europe to the Persian Gulf and beyond. Compared to the sea route via the Suez Canal, this route’s distance shrinks by more than half, which brings the term and cost of transportation down. If the present delivery time on this route is over six weeks, it is expected to decrease to three weeks through this corridor. Hence, the INSTC not only saves time, but also decreases cost.

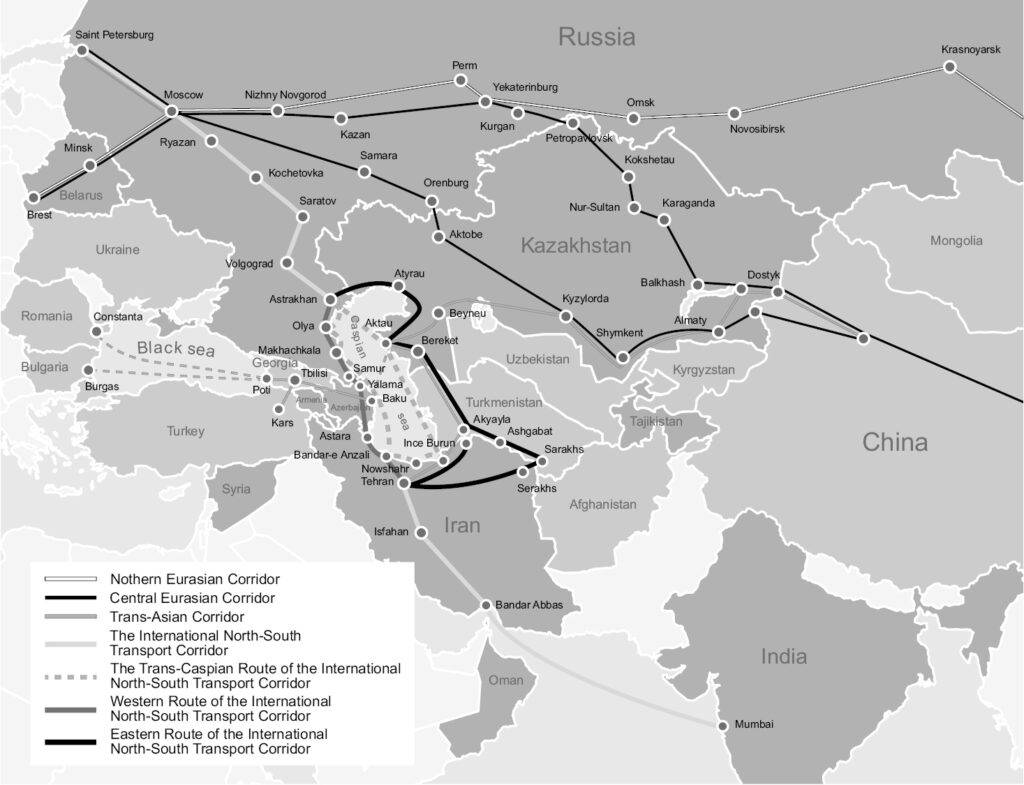

The project is planned to have three routes (see Figure 1):

Read also

- Western route: Connecting the Caucasus to the Persian Gulf

- Central route: Connecting the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf via Iran

- Eastern route: Connecting Central Asia to the Persian Gulf

In my March 2021 analysis “Armenia and India’s Vision of ‘North-South Corridor’: A Strategy or a ‘Pipe Dream?’” I warned that Armenia’s inability to play an active transit role between Russia/Europe and Iran/India will isolate the republic from regional trade. Between 2005-2018, Armenia did little to finalize the north-south strategic highway connecting its northern border to the southern border, mainly due to public corruption and carelessness. In late 2018, a criminal case was opened in Armenia’s North-South Highway project. Today, Armenians are bearing the fruit of this strategic mistake. For the past two decades, Azerbaijan took several initiatives in this direction and boosted its geo-economic position in the region.

This analysis will shed light on Russia’s post-Ukraine war vision related to the INSTC and how Russia’s foreign policy thinking is being shaped by regional trade interconnectivity, Azerbaijan’s growing importance for Russia and its implications on Armenia and the region.

Importance of North-South Trade for Russia amid the post-Ukraine War Regional System

In his paper “Russia and Middle East Need International North-South Transport Corridor” published in the Valdai Discussion Forum and presented in the fourth session of the 11th Valdai Club Middle East Conference on February 2022, Russian economist Evgeny Vinokurov shared his views on why Russia and the Middle East need the INSTC and how “its development can help countries seize post-crisis opportunities and foster economic recovery.”

Vinokurov noted that the launch of this corridor would contribute to the “formation of a macro-regional transport and logistic system,” which he calls the “Eurasian Transport Framework.” It will serve as the basis of the development of trade and investment partnerships within Eurasia. The report argues that interlinking the INSTC and the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railways can also have a significant favorable impact on the EAEU member states where connectivity will enable the expansion of railway container traffic between the EAEU, Georgia and Turkey. Vinokurov argues that in the long term, the INSTC may become a development corridor for the EAEU. “Apart from increasing trade volumes, the development of the INSTC facilitates the construction of industrial parks and special economic zones along the transit route, as well as industrial cooperation and the establishment of production and logistics chains with major emerging economies in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean,” he concludes.

In a report published by the Valdai Discussion Club in February 2023 titled “The Middle East and the Future of Polycentric World,” Vitaly Naumkin and Vasily Kuznetsov argue that with Russia reorienting its trade toward Asia, the role of the Middle Eastern countries, mainly in the Persian Gulf, will increase. “If the effect of the transformation of the oil and gas and food markets is mainly short or medium-term, the revolutionary changes in the global transport and logistic systems have a more lasting and systemic impact,” write Naumkin and Kuznetsov. Most importantly, the report argues that despite the difficult situation in Syria and the stalling project to connect the Syrian railway network with the Iranian railway, there are still prospects in this area as well. If the INSTC becomes operational, Syria may be linked to the transport hubs in the Persian Gulf, while Russia for the first time in history would have direct railway access to its military port in Tartous on the Syria coast of the Mediterranean Sea. This is the strategic goal of Moscow, which has both geo-economic (increase in trade activities with the Middle East) and geopolitical (consolidation of political and military presence in the Middle East) objectives in the region. According to the report, this will lead, first, to a strengthening of the positions of Iran, Iraq and Syria in the global transport infrastructure and, second, to at least partial involvement of the Middle East in the Eurasian space. This would also reflect Russia’s main geopolitical aim in the Middle East to minimize US influence in the region.

Last fall at the “Russia-Middle East” International Expert Forum in Pyatigorsk, one Russian expert, who must remain unnamed due to Chatham House rules, said that the “International North-South Transport Corridor is existential for Russia,” since after the war in Ukraine, it is the only strategic trade route left for Russia to engage with the outside world. It is within this context that we have to analyze the recent Russian-brokered rapprochement between the Gulf states and Syria. Russia aims to stabilize the Middle East and facilitate regional economic interconnectivity (between the Caucasus and the Middle East) to attract investments and bring political stability across the region as north-south trade is a win-win solution for Russia, Iran and Gulf Cooperation Council member states.

To facilitate regional trade interconnectivity, on April 7, 2023, Iraq and Iran agreed to complete the Shalamcheh-Basra railway which was postponed for years due to economic reasons. Although short, the vital 30-kilometer railway line linking Iraq’s Basra to Iran’s Shalamcheh is a first step to link Iraq to China’s “Belt and Road Initiative,” thus establishing a trade channel between Tehran and Damascus. Some observers argue that this railway is part of “Syria’s reconstruction deal.”

The Geo-Economic Importance of Azerbaijan in the Context of the North-South Corridor

Azerbaijan’s geography and developed infrastructure compared to Armenia have made it attractive to play a regional transit role. This factor has not only boosted its geo-economic position, but also in the coming years will boost its geopolitical position and increase its leverage over Russia, Iran and the EU.

In this direction, Baku has taken important steps to connect its railways to Iran. In 2017, Azerbaijan constructed a road with a length of 8.3 kilometers from Astara of Azerbaijan to the Iran railway line up to bridge over the Astarachay River on the southeastern side of the country. Also, a railway bridge was constructed over the river. Additionally, a road with a length of 1.4 kilometers from the railway bridge over the Astarachay River up to the cargo terminal in the Iranian territory was built to connect both sides to each other. Meanwhile, Baku still continues the construction of the railway station and terminal; however, the process was halted due to the sanction and lack of financing.

To connect the railways of Azerbaijan to Iran, in March 2019, the official opening ceremony of the Gezvin-Rasht section (175 kilometers) was held, yet both countries are aiming to finalize the construction of the Rasht-Astara section (164 kilometers) in Iran. To this aim, in March 2018, the former Iranian President visited Baku and signed an agreement to finance the construction of the Astara-Rasht railway in Iran. After finalizing this railway, Iran will be connected to Azerbaijan through the railway and Baku can have access to Nakhichevan via the Iranian railway. It is expected that the volume of cargo traffic along this corridor would be between 5-10 million tons per year in the beginning and later increase dramatically.

In September 2022, Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan signed a declaration on the development of the INSTC project. The parties expressed “their readiness to cooperate in estimating and analyzing the infrastructure and options to use the corridor.” According to the declaration, a 4,000+ kilometer long route will join Russia’s Baltic ports to the Persian Gulf. However, expanding the route capacity will be impossible without the construction of the Rasht-Astara railway section. [Refer to this infographic created by the Valdai Discussion Club]. This may take several years. So far, India has invested around 2.1 billion USD in this project with part of the funding spent to develop the transport and logistic infrastructure in Iran. When Russian President Vladimir Putin visited Tehran on July 19, 2022, he discussed his vision for the INSTC and expressed Russia’s readiness to construct the 164-kilometer Rasht-Astara section of the bridge and allocate 1.5 billion USD for this purpose. He also expressed Azerbaijan’s readiness to take part in the construction efforts.

However, given Azerbaijan’s decision not to risk being sanctioned by the US for investing in the railway project in Iran, Tehran turned to Moscow. After the war in Ukraine, Moscow’s interest grew in the INSTC. Taking into consideration the restriction of trade between Russia and Eastern Europe and the decline of the role of the northern corridor in connecting China’s trade routes to Europe through Russia, and on the other hand, the signing of the “Preferential Trade Agreement” between Iran and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the increase of trade between Russia, Iran and India, Moscow has increased its interests to the INSTC and the construction of the Rasht-Astara railway section. For this purpose, on January 18, 2023, Russia’s presidential aide and State Council Secretary Igor Levitin visited the railway section and promised that Russia will invest in the project and finalize it in three years, thus connecting Iran to Azerbaijan through the railway.

According to Iranian expert Vali Kaleji, Iran and Russia aim to revive the Soviet railway in the region. “The construction of the Rasht-Astara railway, the 55 km Zangelan-Nakhichevan railway line through Iranian territory and the revival of the Soviet-era railway (Jolfa-Nakhichevan), are main important rail projects that regretfully have not yet been fully completed,” says Kaleji. Also, by reviving the Jolfa-Nakhichevan railway, Iran will be connected to Armenia by a railway through Nakhichevan, and there will be no need for the construction of a railway connecting Iran directly to Armenia via Meghri. According to this logic, regional interconnectivity and interdependence in regional countries will minimize the possibility of new wars in the region. To decrease military pressure on Armenia, Iran has offered Azerbaijan to agree on an alternative road bypassing Armenia. On March 11, 2022, an MoU was signed between both countries where Azerbaijan proper was going to be connected to Nakhichevan through railways and highways bypassing Armenia. The agreement mentions that four bridges (two railway and two road bridges) are going to be built on the Arax River. However, even the Iranian offer has not stopped Azerbaijan’s appetite for Armenia’s southern territories.

Azerbaijan has some cards to pressure Tehran and Moscow and both are dependent on Baku for transit. There are other alternatives to the INSTC where countries such as Turkey and Georgia, as well as Azerbaijan, are involved. In March 2022, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey and Kazakhstan issued a joint statement on the need to strengthen the “Middle Corridor,” which aims to facilitate trade between China and Europe through Central Asia and the South Caucasus bypassing Russia and Iran. For this purpose, in the same month, the Georgian railway company announced that it started collaborating with Azerbaijani and Kazakh companies to create a new shipping route between the Georgian port of Poti and Constanta in Romania. To facilitate this process, Azerbaijani and Georgian leaders recently visited Central Asia. Tuba Eldem in her publication in the German Institute for International and Security Affairs “Russia’s War on Ukraine and the Rise of the Middle Corridor as a Third Vector of Eurasian Connectivity” argues that the war in Ukraine has disrupted the northern corridor (also known as the New Eurasian Land Bridge) connecting Russia to Europe due to sanctions. Hence the only “alternative route for this corridor” is the Middle Corridor. The author also brings in the “Zangezur Corridor” narrative, arguing that “the importance of opening the Zangezur Corridor and of the construction of its continuation via the Kars–Nakhichevan railway line…(the Zangezur Corridor) will not only enable Azerbaijan unrestricted access to its Nakhchivan exclave without needing to pass through any Armenian checkpoints, but it will also provide Turkey a direct route to the Caspian basin and Central Asia.”

Russia’s and Iran’s occasionally “passive” actions toward Azerbaijan reflect their trade and transit dependence on Baku, which, in turn, is using this leverage to engage in military provocations toward Armenia and humiliate Russian peacekeepers in Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh).

Implications of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) and Russia-Armenia Relations

After the first Artsakh war (1990-1994), Iran lost its railway connection to the South Caucasus when Armenian troops captured territories outside the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO). Today, Iran has a chance to make an economic comeback in the region. If the railway connection is completed, Iran will have two railway routes to Russia. One will run along the east of the Caspian Sea through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, and the other will link Russia, Azerbaijan and Iran along the western shores of the Caspian through the South Caucasus. Of course, if in the future Azerbaijan lifts its blockade on Armenia and trade routes open, and Russian border guards secure the transit between the routes connecting Azerbaijan to Nakhichevan through Syunik (as mentioned in the ninth article of the November 10, 2020, trilateral statement), then Armenia can also play a transit role in the region.

It’s worth noting that the ninth article of the November 10, 2020 trilateral statement does not mention the word “corridor” and instead says, “All economic and transport links in the region shall be unblocked. The Republic of Armenia shall guarantee the safety of transport communication between the western regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic to organize the unimpeded movement of citizens, vehicles, and cargo in both directions. Control over transport communication shall be exercised by the Border Guard Service bodies of the FSS of Russia.” Many Azerbaijani experts argue that the word “unimpeded” is key here, meaning that the Armenian side will not interrupt the border crossing of Azerbaijani vehicles. On the other hand, although this route doesn’t have any extra-territorial status in its nature, mentioning that it will be controlled by the Russian Border Guards Service clearly indicates that it will be Russian and not the Armenian side that will control the border traffic. Of course, this does not mean that Armenian custom checkpoints will not be installed. Any comparison of this route with the Berdzor (Lachin) Corridor which has clear extra-territorial status in the trilateral statement is false.

Even Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister spokesperson have mentioned on several occasions that the idea of a “corridor” is false. Russia wants to take control of these routes to ensure their safety from any possible Turkish-Azerbaijani aggression. During my trip to Russia in November 2022, a former Russian diplomat informed me that during the negotiations ahead of the signing of the trilateral statement on November 10, Russia was being pressured by Ankara and Baku to give a certain extra-territorial status to the route in Syunik. Moscow rejected this proposal, knowing well the true Turkish-Azerbaijani intention in Syunik.

Concerns about mounting military and political pressure on Armenia to compromise over the Armenians in Artsakh are on the rise. However, in this “battle of corridors,” the true intention is not Artsakh but the importance of Syunik alongside the competing trade routes. Yerevan has few options left to boost its position in the region:

- Finalize the north-south route and attract regional investment to develop an infrastructure for this purpose.

- Actively participate in regional infrastructure projects by organizing conferences and taking advantage of the diaspora’s institutionalized networking system in the Middle East.

- Expand its diplomatic presence in the Persian Gulf states. Establishing diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia should be a priority for Armenia’s foreign policy, in addition to establishing business committees between Armenian businessmen (in the Gulf states) to facilitate trade interactions and identify possible ways to bring Gulf investment in several economic (agricultural, service, IT) sectors in Armenia within the context of north-south trade.

- Armenia and the diaspora should continue exposing the real geopolitical threats coming from the “Middle Corridor” toward Syunik and northern Iran and instead actively push for the north-south trade and the interconnectivity between the Black Sea and the Persian Gulf which will open European and Asia (including Middle Eastern) markets in front of Armenian products.

- Many international and regional actors would aim to trigger conflicts and wars mainly between Armenia and Azerbaijan or Azerbaijan and Iran to destabilize the region and torpedo the north-south trade aiming to isolate Russia and Iran. Some countries would also seek to destabilize Syunik, showing Armenia as an unreliable partner in transit projects. That’s why Yerevan should be careful not to turn into a proxy of regional or international actors and instead aim to provide its army with deterrent weapons to halt any future Azerbaijani incursions.

- Finally, Iran’s initiative to open a consulate in Syunik was a diplomatic victory for Armenia. Given India’s and Russia’s interest in the region, Yerevan should take proactive diplomatic steps to encourage the opening of Indian and Russian consulates in the region. Meghri can be another possible location due to its strategic position along the north-south highway bordering Iran. Other friendly countries in the EU (France) should be encouraged to take a similar step.