by The Armenian Mirror-Spectator

By Aida Zilelian

It seems impossible to memorialize the life of a prolific translator a decade after his passing. Especially if you knew him for much of your life. I looked at my calendar today and it marks eleven years this May since Aris Sevag died. I don’t reflect on how much time has gone by. For me, his death stands still. It was only after his passing that I was able to understand who he truly was, beyond his life’s work and his care and love for me as my stepfather.

For the Armenian community, Aris was a treasure. He edited and translated hundreds of literary works from Armenian to English interchangeably, bringing to life excerpts, articles, books, and memoirs of Armenians who would have long been forgotten had it not been for his voracious — compulsive, really — desire to extract the meaning of words in its purest divination. I recently discovered that a collection of short stories, seven of which he had translated, Armenian-American Sketches by Bedros Keljik was selected as the winner of the 2020 Dr. Sona Aronian Book Prizes for Excellence in Armenian Studies. Aris’ bibliography could fill volumes. One of his most notable masterpieces was his translation of Armenian Golgotha (2010, Knopf), a 500-page memoir by the priest Grigoris Balakian, who was arrested and deported during the Armenian Genocide, where he bore witness to the annihilation of his people.

Read also

Aris told me once, “To say this is devastating to read…. It can take years off your life.”

He recounted the stories of his father, a professor of Physics, Dr. Manasseh Sevag, who was a Genocide survivor and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

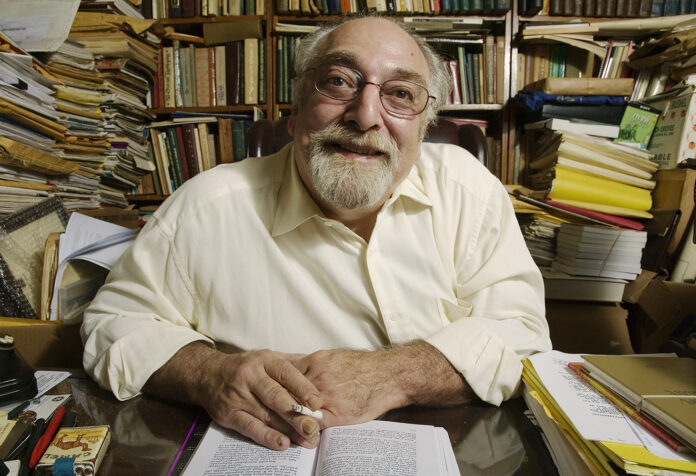

The only way to truly understand his dedication to his craft, his passion for words and knowledge, was to step into his study, as I did for many, many years. He had so many books, custom shelves were built to fit his study from floor to ceiling. His desk was surrounded by a fortress of dictionaries and thesauruses. Oftentimes, one had to call out to him or look over the towering stacks to see if he was in the room. Somehow he was able to fit a clock radio (which perpetually played classical music), an amber ashtray, a small, high-powered fan and his asthmatic printer, alongside his collection of books. It was comedic, really. He lived and breathed, ostensibly, to edit and translate. In his leisure time, I would catch him in the middle of proofreading anything he saw in print — a restaurant menu, a poster on the subway, a billboard sign, a playbook at the theater.

I imagine, this is the elaborated perception of him, for many of his friends and acquaintances. When I first met him, I was 8, a timid and sad little girl living in a home of turmoil and chaos. He was Mr. Sevag, my third-grade teacher. At the time, I attended an Armenian school in Woodside, Queens. It was a fledgling school with a very small student population. It was where my mother would meet him, and they would marry years later. Not only did he teach at the school, but he was also the school bus driver. He was 35 years old and married with a young son. He seemed a happy wanderer, unsure of himself, yet invested in life.

Eventually, he left teaching for a brief stint in real estate, and then settled into a position as managing editor at the English-language Armenian Reporter, one of the leading Armenian newspapers, for 20 years. He moved on to become editor of Ararat, a highly-respected Armenian literary journal of 50 years at the time, publishing works of notable historians, writers and journalists. At the end of his career at the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), he continued freelance editing and translating.

In a New York Times article “Severing a Link, Word by Word; As Language Erodes, Armenian Exiles Fear Bigger Loss,” Aris reflected candidly about how Armenians may soon loose grasp of their native literature, “We are losing our multigenerational thread. We are losing our ability to understand the Armenian gestalt, our inner world.” Perhaps this is his demure attestation to what drove him to edit and translate so dedicatedly.

The aspect of him that I embrace more fully than any other was his ability to give of himself completely. It was his most compelling grace and his detrimental flaw. I would slip into his office and take a cigarette from his pack, sit on the library bench, and talk. Sometimes I wouldn’t. I would bring him my novice stories, which he returned to me diligently, his neat, red pen marks dancing across the pages. I asked him once, in the midst of a neurotic philosophical crisis: “How do you become intelligent? Where does intelligence come from?” He grinned. “Books,” he said. “You have to read as much as you can.”

After his passing, I received an email from his best friend in college, Don. He relayed stories of my stepfather that shouldn’t have surprised me, but did anyway. On one particular trip to Harvard for a game, the car overheated so many times that it took Aris, Don and their friends 12 hours to drive from Pennsylvania to Boston. Aris entertained them with his violin, playing show tunes and concertos while sprawled out on the car roof. The following year, they dressed up as police officers and pretended to arrest one of their colleagues, causing complete mayhem on campus. And a more predictable bit, Aris and Don revived Penn’s humor magazine, The Punchbowl, where Aris wrote satirical articles and parodies.

Don was kind enough to forward an exchange between him and my step-father, where they discuss Morse Peckham’s Man’s Rage for Chaos, which theorizes that order is man’s freedom, although we rage for chaos. Aris writes to Don, “If it weren’t for the fact that I used my computer to read Peckham’s statement about Man’s Rage for Chaos and tell you I enjoyed reading it, I could swear no time has passed since our college days. That feeling, if momentary, is an instance of man’s ability to reign supremely, albeit ever so briefly.” Two weeks later, Aris passed away.

For our family and his dearest friends, he was a legend. In writing this, it has been a great strain to forfeit to the economy of words. How I wish he was here to read this. Red pen in hand, he’d have much work to do, I’m sure.

(Aida Zilelian is a first-generation American-Armenian writer, educator and storyteller from Queens, NY. She is the author The Legacy of Lost Things (2015, Bleeding Heart Publications) which was the recipient of the 2014 Tololyan Literary Award. Aida’s most recently completed novel, All the Ways We Lied, is slated for release in January 2024.)