Meritocracy Projects as a solution option

On the occasion of the 7th anniversary of the “Kolokol” newspaper founded by him and Ogarev in 1864, the Russian revolutionary Hertzen /Gertsen/ wrote: “New Russia has a great task to develop the life of the people… with a mature mind and foreign experience. It (New Russia – A.A.) must save the people from the imperial autocracy and from themselves.”

Of course, the last two words attract attention. Save the people from themselves? How: Or, more importantly, for what, if they themselves don’t want to be saved? Are you a Democrat? Do you want the people to choose their destiny and future?

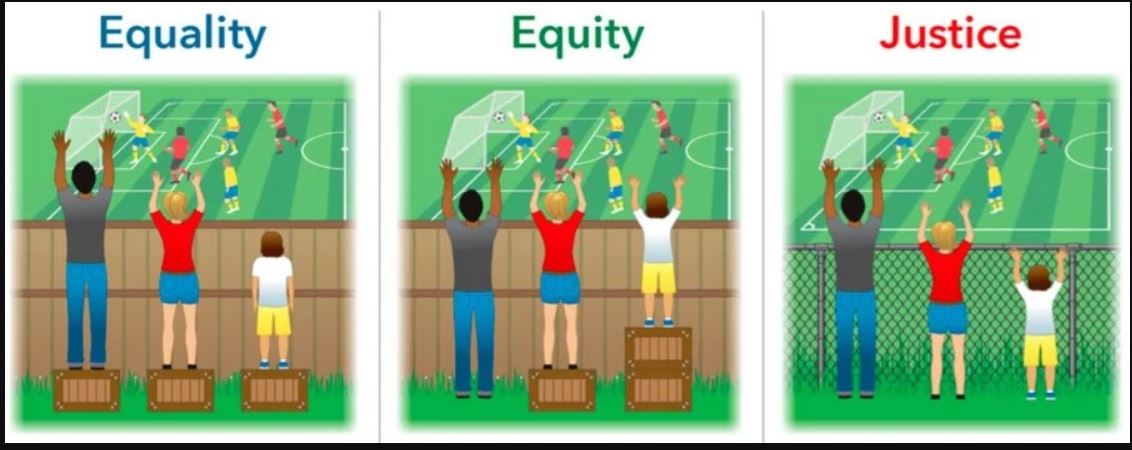

If you want to, you have to be prepared for them to choose a future that they think is there but isn’t. It only looks beautiful on the flag: liberty and equality. In reality, they are somewhat contradictory things. Economists were the first to notice it, naturally. As early as 100 years ago, the English economist John Maynard Keynes observed that freedom, equality and efficiency cannot be simultaneously developed to the same extent: you must always sacrifice the other two when choosing one. A constant tension between liberty and equality also emerges in politics.

Read also

What if everyone has equal rights and chooses not freedom, and slavery, and destruction? Is it worth saving the people from themselves? A partial solution that somewhat alleviates that tension is meritocracy or aristocracy. In what cases is it possible? This question can be approached from the opposite side. Some factors hurt creating such a system and are weakly or strongly expressed in different countries.

Those negative factors are 1/ corruption, 2/ organized crime, and 3/ egalitarianism, that is, egalitarian prejudices. The negative effect of the first two is apparent: corruption undermines the “social elevators” that can identify elites worthy of governance. Organized crime, when, say, state-owned private racketeers get a share of the business through violence or administrative leverage, prevents the formation of business elite. The third factor is more complicated. In democratic states, not those with the highest level of awareness (competence) lead, but those whom most citizens want to see in power, who, to put it more simply, the people like.

The unacceptability of such a situation at the level of individual institutions is obvious, and no one argues with it. Hospital staff do not vote on who will operate on a patient. Or, children and their parents do not choose the teacher who will hang the best curtains in the classroom. In an orchestra, musicians do not struggle to play something instead of a pause written for them. Forming such awareness at the state level faces specific barriers, including worldview.

It is clear that it is impossible to create a meritocratic social order in, say, Russia because the first two factors are developed there: corruption and organized crime, and that is why all attempts to save the people “from themselves” have failed from the beginning.

On the other hand, the states of the West are not like that because they are built on Enlightenment, Modern, including “egalitarian” ideas, which were widespread in Europe since the 18th century and served as the basis, in particular, for the US Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Those countries do not intend to give up “egalitarianism,” but the whole problem is that they do not need a meritocratic government; they have been working for centuries to form elite, that is, specific “non-meritocratic” mechanisms to “save” the people from themselves.

It is another matter that they sometimes need to work more effectively. However, in countries that do not have such traditions, in Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and New Zealand, there may be a need for meritocracy. That system has its characteristics in each country. Still, the common thing is that those countries understand that Western “egalitarianism” coming from the 18th century should be approached at least “creatively.”

In the post-Soviet space, it is also worth thinking about Meritocracy projects, on the one hand, not renouncing general democratic principles, and on the other hand, not turning those principles into some dogma, the implementation of which hinders the efficiency of politics, economy, security, and endangers the future of the state.

In other words, here you have to go between the Scylla and Charybdis of the arbitrariness of the “uppers” and mob rule. It is wrong for anyone to say, “We will make you happy.”

It is equally wrong when it is said: “Well, what to do? The people decided to get into this…”? Finding the golden mean is difficult, but it exists in each specific country and within each particular period.

Aram ABRAHAMYAN

“Aravot” daily, 06:06.23