Pitirim Sorokin suggested governments engage in a “unified system of public morality.”

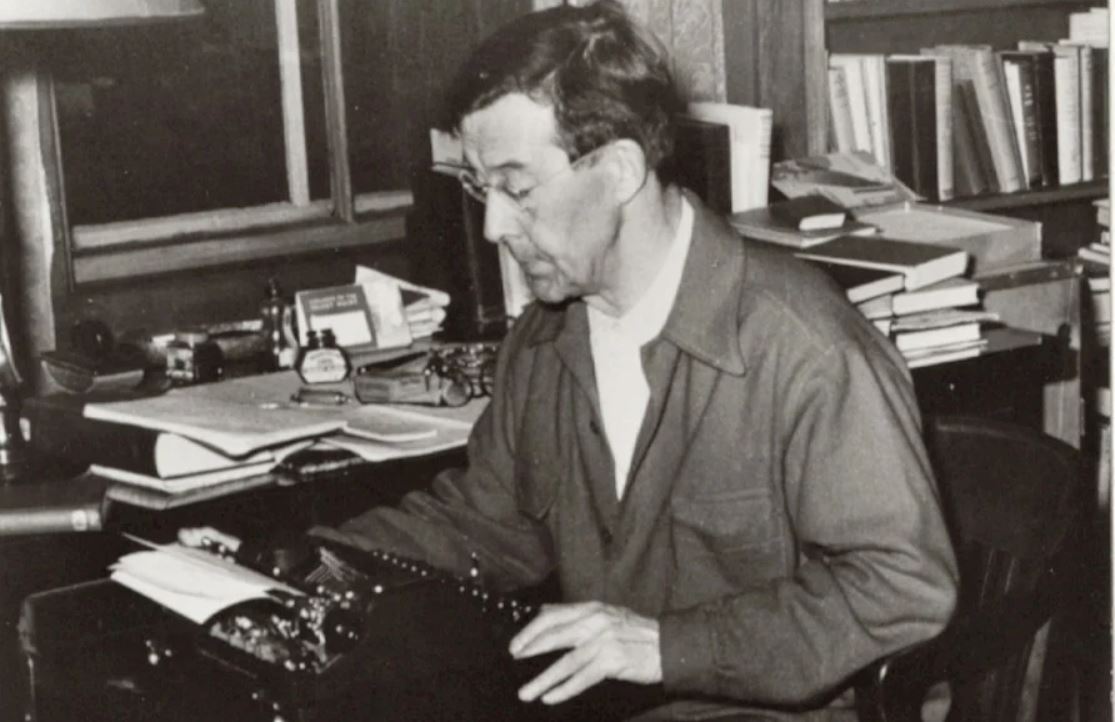

In 1959, Russian and later American sociologist Pitirim Sorokin published a book called ” Power and Morality: Who Shall Guard the Guardians? Sorokin sent copies of the book to the then US President (Eisenhower), the Secretary of State, several congress members, and senators. He also remembered his homeland, where he spent the first half of his life, and sent one copy to Nikita Khrushchev.

All recipients sent very polite thank-you letters to the scientist. Presumably, they hadn’t read that book; otherwise, they would have seen what the author thought about power—moreover, any government.

One of the book’s chapters has a very eloquent title: “Criminal Nature of Heads of State.” A follower of Tolstoy’s worldview, Sorokin was convinced that any government, in terms of the number and quality of criminal offenses, was superior to ordinary citizens of the same country. Examples of emperors, kings, presidents, prime ministers, and other leaders are given. There are five generalizations in that passage, of which the first two are the most interesting for us. The first is as follows.

Read also

“When the moral and mental qualities of the rulers and their subjects are measured by the same scale, not by double standards, it turns out that the rulers stand out with a stronger expressed dualism, a much sharper moral and mental schizophrenia than the ordinary members of the given society.”

Why does a sociologist talk about schizophrenia? The point is that, according to Sorokin, a person who aspires to power, as a rule, does not have “moral inhibitions” and lacks reflection and concern, which are specific to us- ordinary people. He always has to give the impression of a purposeful and determined person, and that’s why the crowd likes him. In fact, the apparent duality of thought and moral values is typical for such people. That is what the sociologist’s second generalization is about.

“On the one hand, there is a larger share of gifted and, on the other hand, mentally deficient people in the ruling circles than among ordinary citizens. The percentage of egoists, braves, those who show cruelty and indifference to other people, hypocrites, and cynics is higher in the ruling groups than among the common people,” concludes Sorokin.

According to him, crusades, purges, holy wars, and occupation of other territories are allegedly happening for God’s sake, nationalism, purity of the nation, etc. But the real motive is the monstrous, selfish interests of those in power.

The author sees the way out, naturally, in the limitation of power. He shows by examples that those with unlimited power commit more severe crimes than those in power whose appetites are restrained by some constitutional norms. In the second case, crimes against property, corruption, and abuse of state leverage in favor of one’s material needs dominate. But there is also a second remedy that Sorokin suggests: governments should engage in a “unified system of public morality.”

In other words, appetites must be curbed not only by laws and constitutions but also by moral norms. But for this mechanism to work, that “unified” system must exist; that is, moral models must be acceptable to most of society. For Sorokin, it is perhaps a modernized Tolstoyism, an “unofficial” Christianity, some of which he also saw in American Protestant culture.

However, in this respect, for any society, unique systems should operate, in contrast to constitutional norms, which are more or less universal and are based, in particular, on the separation of the branches of power. Everything is more or less clear here, although it has not been used in Armenia for 30 years. And what remains of the “morality system,” its formulation, requires more outstanding intellectual efforts.

Aram ABRAHAMYAN

“Aravot” daily, 13.06.2023